SA-US relations: Ramaphosa must insist on South Africa’s independence

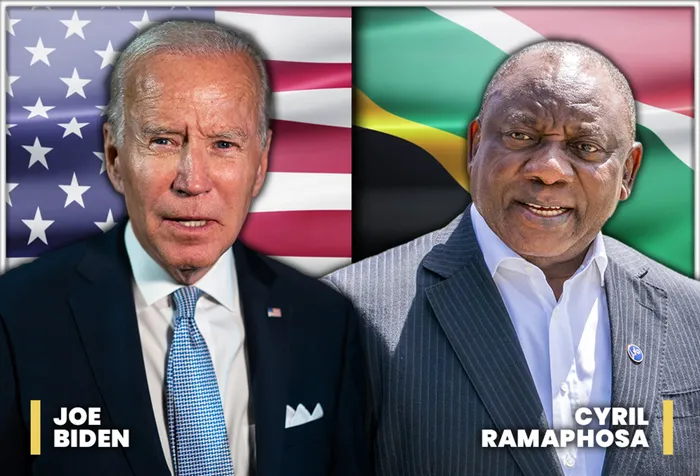

Graphic: Timothy Alexander/ African News Agency – South Africa and the US share an important strategic partnership, which has been cemented by both countries being liberal democracies, the writer says.

By David Monyae

South Africa’s President Cyril Ramaphosa will meet his United States counterpart Joe Biden in Washington DC on September 16. The meeting, which comes a few weeks after the US Secretary of State Anthony Blinken’s visit to South Africa, will build on the extensive and deep relations that their two countries have shared for more than two centuries.

South Africa and the US share an important strategic partnership, which has been cemented by both countries being liberal democracies. This partnership manifested most visibly on the economic front. The Southern African regional powerhouse is the US’s biggest trading partner on the continent with trade between the two parties reaching US$21 billion in 2021, about 32 percent of the US-Africa trade in the same year. The US has 600 companies operating in South Africa and has accumulated an FDI (foreign direct investment) stock of US$7.8 billion according to 2019 figures. South Africa’s FDI stock in the US is estimated at US$4.1 billion.

The US FDI contributes to the creation of much-needed jobs for South Africa’s young population. Most of the US companies use South Africa as a gateway to the African market. Moreover, South Africa also benefits from the US Africa Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) which grants preferential treatment of goods from selected sub-Saharan African countries. Other trade arrangements involving the two countries include the Trade and Investment Framework Agreement of 2012 and the Trade, Investment and Development Co-operative Agreement (TIDCA) signed between the US and the Southern African Customs Union (SACU) of which South Africa is a part.

EXPLAINER: Here's what you can expect from Cyril Ramaphosa's visit to Washington when he meets #JoeBiden . @NkalaSizo and @gwinyaitaru share their views. Read more here: https://t.co/G4oJEI3c4R

— The African (@TheAfrican_coza) September 15, 2022

🎥 by @FootballFaan #TheAfrican #ramaphosa pic.twitter.com/kENh0zjoik

As such, Ramaphosa will seek to encourage more trade and investment from the US to bolster South Africa’s struggling economy.

It is important for President Ramaphosa to bear in mind that he goes to the White House wearing not only the national hat but the continental one too. As such, in his deliberations with Biden he must highlight Africa’s interests as captured and articulated in the AU Agenda 2063.

The US has the potential to play an important role in driving economic transformation in Africa through supporting the implementation of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) and helping narrow the infrastructure funding gap in Africa among other ways.

Nonetheless, despite their thriving bilateral relationship the two countries seem to be drifting apart on global issues of late. Firstly, Ramaphosa is one of the principals of the BRICS grouping whose founding mission is to transform the current global order which the US, being its chief architect, expends an enormous amount of resources defending. The BRICS countries, acting as representatives of the global south, feel aggrieved by the inequities of the global order which favour the global north at the expense of the global south. Secondly, the Covid-19 pandemic further laid bare the differences between South Africa and the US worldviews.

Ramaphosa was critical of the US and other rich countries’ rush to hoard Covid-19 vaccines leaving developing countries especially in Africa without access to vaccines, which the United Nations had declared a global public good. Further, the US failed to support South Africa’s quest in the World Trade Organisation (WTO) to have intellectual property rights on vaccines waived to allow for their production in more countries. This episode raised questions one the United States’ commitment to multilateralism on the one hand and the sincerity of its partnership with Africa on the other. Third, South Africa has steadfastly refused to join the US-pulled bandwagon of condemning and isolating Russia for its invasion of Ukraine beginning February this year.

South Africa has insisted on adopting a neutral stance on the Russia-Ukraine conflict arguing that condemning and punishing one of the protagonists will only make it harder to bring them to the negotiating table. The US and other western countries’ sanctions on Russia have added to the deterioration of the global economy with developing countries being the hardest hit.

The war in itself is a manifestation of the terminal deficiencies of the post-1945 US-sponsored global order which South Africa and its BRICS allies have protested against. Moreover, on climate change the US and South Africa largely see eye to eye and have both committed to fighting climate change by reducing striving to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and build greener economies in their countries. However, Ramaphosa’s administration must commit to obligations that South Africa can handle, particularly when it comes to transitioning from fossil fuels to renewable energy.

The US can be an important partner for South Africa in implementing its Just Energy Transition policy in an economically and socially sustainable way in terms of technology transfer and finance.

The US is aware of its waning global influence and also aware of South Africa’s strategic value as an important voice on the African continent. Biden’s invitation of Ramaphosa to the White House is partly calculated to court South Africa’s support on important global issues in light of the US-Africa Leaders Summit coming up in December.

At the same time, the US is also important to South Africa within the purview of the North-South relations part of its foreign policy. However, it is important for Ramaphosa not be intimidated or co-opted by the economic might of the US and act in South Africa and Africa’s best interests.

In Washington Ramaphosa must insist on South Africa’s independence in making decisions on its foreign policy while emphasising co-operation on issues that can yield mutual benefit for both countries.

Monyae is an Associate Professor of International Relations and Political Sciences and Director of the Centre for Africa-China Studies at the University of Johannesburg.

This article is original to the The African. To republish, see terms and conditions.