The power of the spoken word

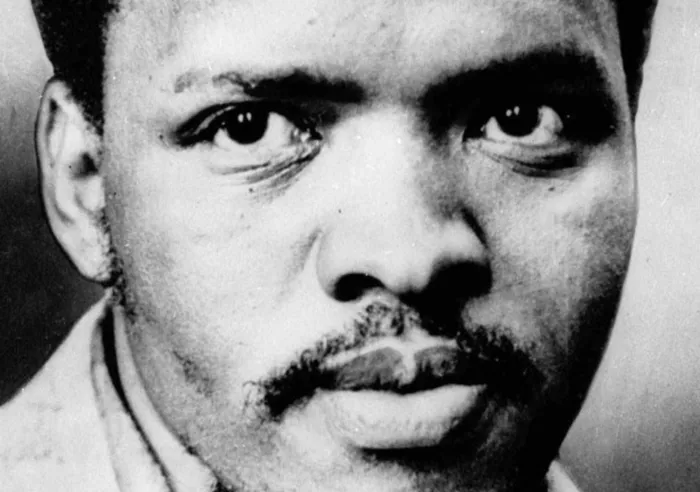

Picture: ANA files – Steve Biko, Black Consciousness leader who was murdered by the Apartheid police agency in 1977. ‘It is a good thing that student leaders are able to leave the ivory tower of a university and come down to feel the pulse of the people in the community’. These words uttered by Biko on their first meeting influenced the choice the writer made to serve the oppressed poor people of South Africa as a human rights lawyer, he says.

By Wallace Mgoqi

From childhood, as far as I can recall, certain words were spoken to me, especially by my own biological parents, both of whom were staunch Christians, who wanted to make sure they brought up their three boys and four girls the right way.

The first time someone outside my own family spoke words that stayed with me to this day, was our high school Principal, the late Prince Makhonza Ngambu, who was in the habit of asking the class to close the textbooks and just listen. He would say, among other things:

“Respect time, and time will in turn, honour you.”

I have conducted my life in line with this adage, and I can say with no fear of any contradiction, I have been better off, because of it.

Even through initiation, a strong custom observed by Xhosa, even in urban areas, to this day, to mark transition from boyhood to manhood, many words were spoken. But the second time I was impacted by words someone other than my parents said, was when my paternal uncle sat me down, when he heard that as I was going to university.

I had impregnated a young girl, who lost her parents, mother first and father later at five years old and 12 years old respectively and was way behind me in her schooling. He said much as I was going to be educated now, unlike any of the them in the entire clan, I must be careful never to look down upon an uneducated person (iqaba in Xhosa). He said because if I did that I must know that I am insulting them, because “you never know the circumstances that caused a person not to be educated”. He said: “It was our desire to be educated, but circumstances did not allow us”.

He cautioned that now that I was at university, I must not be taken away by attractive girls, and despise a child who is an orphan. That weighed heavily on me, such that I vowed I would honour his words. That girl became my wife, and we have been married for forty eight years now.

Whilst at Fort Hare University, in my final year, I was elected by the Social Work students to be the chairperson. In the height of the black consciousness movement, we also wanted to be relevant and invited someone we heard had radical views on social work, the director of the Black Community Programmes (BCP), now Professor Bennie Khoapa.

But the rector of the university, (a member of the Broederbond, a secret body, which was an extension of the Nationalist Party) got wind of it and pronounced that such a person was not welcome at the university, so he was banished from coming. Students quickly arranged that my deputy, Mthobeli Phillip Guma and I travel to Kingwilliamstown to meet this man.

We hitch-hiked to Kingwilliamstown, and since there were no cell phones in those days, it still puzzles me how we found our way. On arrival there, we were met by someone who directed us to hitch hike further to Mt Coke Hospital, just a few kilometres from Kingwilliamstown.

On arrival at the hospital, we were informed that our man was on his way to meet us. In a matter of minutes he arrived, and we sat on the floor, in the foyer of the hospital, and he shared with us what he was going to share with the students back home. After our meeting, he offered us a lift in his car, and told us he wanted us to meet his friend.

As we left town we entered Ginsberg location, and we approached a house surrounded by many cars. He told us that the people in these cars were from the Bureau of State Security (BOSS ), there to guard Steve Bantu Biko, who was “under house arrest” and could only see one person at a time. In the house we were pointed to his room and entered. We shook hands with this dark tall man, who spoke words that have remained with me for my entire lifetime. He said: “It is a good thing that student leaders are able to leave the ivory tower of a university, and come down to feel the pulse of the people in the community.”

These words have been a guiding light in my life, to do everything that would meet the needs of the people on the ground, staying in touch and feeling ‘the pulse of the people in the community’. This made me eschew anything that would take me away from proximity with the people, as life sometimes does when we climb the social ladder.

On completing my Articles of Clerkship to be admitted as an attorney, I was offered a partnership at the law firm where I did my articles, but when I saw the new offices, we were going into I declined the offer, fearing that it was going to be difficult to serve the constituency of grassroots people I was committed to serving. I instead joined the Legal Resources Centre, which dealt with the legal problems confronting the poor in our society.

I can testify that, without any equivocation, and with the benefit of hindsight, the words of Steve Bantu Biko influenced my choice of career, of being a human rights lawyer, who would take up the cudgels on behalf of the poor and vulnerable. It is a choice that was not without a cost. Materially, I was worse off than my contemporaries, who went to establish their own firms to make money, but spiritually I am very rich, with a sense of self-fulfilment from doing the kinds of things I have been able to do with my life.

Sadly, in September 1977, four years later, we had to travel, in a Combi, as friends and followers of Steve Bantu Biko to attend his funeral in Kingwilliamstown, where the late Archbishop Mpilo Desmond Tutu, made the pronouncement that:

“Apartheid was a lie from the beginning, and no lie would last forever.”

Indeed, by 1993 we saw the demise of Apartheid and its formidable architecture crumble in front of our eyes, ushering in the new democratic dispensation with freedom for all guaranteed in our Constitution.

As I started my career, on the cusp of leaving for my first trip to the United States (US) in 1979, a pastor came to our place and said since he had heard I was due to leave the following day, he thought of bringing me a word.

He said: “My child, I want to say to you in everything ‘Thembeka’, because there are no small snakes; when they are poisonous, the size does not matter, the snake kills.” In English, ‘Thembeka’ means: be reliable, trustworthy, loyal, dependable, responsible, discreet, have self-control, be sensitive to others, and be wise. Later in life I was to read a book, No Small Snakes – A Journey into Spiritual Warfare, by Gordon Dalbey.

These words have also shaped my life. In everything I did, I had to make sure that I was dealing with poisonous snakes that kill in the end. I made my mistakes, but I was warned in advance about these things.

In 1984, the University of Cape Town’s School of Economics, hosted the Second Carnegie Inquiry Into Poverty under the able leadership of Professor Francis Wilson. In one of the sessions, I was to address the conference delegates, and was put on a Panel of Speakers, including the iconic, legal giant in Administrative Law, the late Justice Ismail Mahomed, first President of the Constitutional Court. I was scared to the bone, to speak in the presence of this Colossus of the law.

I shared my intimidation with Lindy “Nomthunzi” Wilson, a film-maker and wife to Prof Wilson. She whispered into my ear; “Wallace, you are young, gifted, erudite and black, everyone here is going to be glued to every word you say, just go there, speak your heart and mind.”

After hearing those words, as I ascended the podium, I was oozing confidence, and tackled my assignment, oblivious to any distraction. I was to speak on the Legal Needs of the Poor and had produced a conference paper on the subject and another on Legal Education in South Africa, both of which were published, as conference papers.

As I came back to my seat, Justice Mahomed was the first person to stand up and extend a hand of congratulations.

I was bowled over, such is the power of the spoken word. Lindy Wilson will remain dear to me, and her memory etched on my soul. A right word spoken at the right time, can perform miracles it is “as beautiful as gold apples in a silver bowl” .

The saying is true that each and every one of us, we stand upon the shoulders of those who came before us. They planted with sweat and tears; we are harvesting the fruits of their labours. The words they spoke to us were meant to build us and warn us of the trappings in this life so that we might avoid them and escape like a bird from a snare.

I have experienced the power of spoken words in my life and am a better person because of them.

Dr Wallace Mgoqi is the chairperson of Ayo Technology Solutions Ltd. He writes in his personal capacity.

This article is exclusive to The African. To republish, see terms and conditions.