The nexus between horizontal inequalities and violent conflicts: Kenya

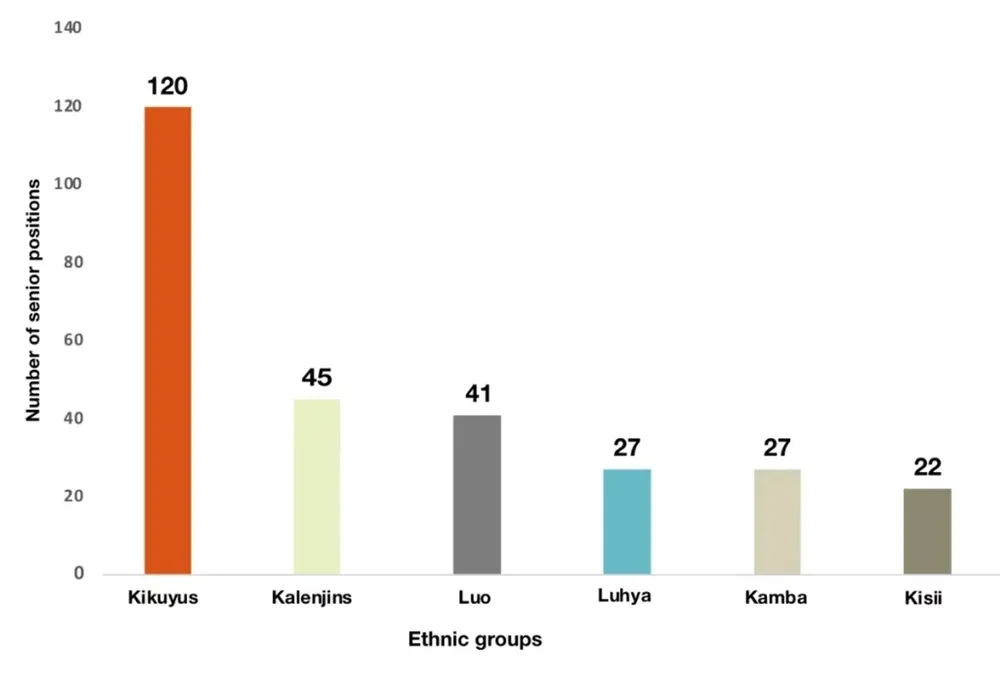

Figure 1: Number of senior positions per ethnic group in Kenya. Graphic: Kenyan Public Service Commission

Horizontal inequalities are defined as inequalities in economic, social or political dimensions or cultural status between culturally defined groups. Picture: Asphotofamily, left; Rantaimages, right.

By Sylvan Odidi

The duration, nature, and potency of horizontal inequalities are vital in comprehending conflict dynamics manifesting in societies.

Horizontal inequalities are defined as inequalities in economic, social or political dimensions or cultural status between culturally defined groups. Relationships between horizontal inequalities and conflict were first discussed by Frances Stewart in the Framework of Collaborative Project Series on socio-economic causes and the impact of humanitarian emergencies and internal conflicts.

It is instructive to note that if horizontal inequalities endure over generations, it is likely to generate resentment and, subsequently, conflicts. Therefore, the duration, nature, and potency of horizontal inequalities are vital in comprehending conflict dynamics manifesting in societies.

Contemporary conflict studies posit that horizontal inequalities result in conflict situations where they intersect with significant group identities. In addition, in circumstances where inequalities between various groups are large, the likelihood of conflict is high.

In this regard, Stewart observes that horizontal inequalities lie at the centre of most violent conflicts in developing nations. Arguably, Kenya falls under the category of countries ranked as unequal globally.

The distinguishing characteristic of Kenyan society lies in its regional and ethnic disparity in wealth spread among citizens. The degree of horizontal inequalities in Kenya typifies the interplay of ethnicity and politics as well as polarised loyalties among key institutional players.

Existing horizontal inequalities in Kenya have culminated in violent conflicts. These conflicts lower economic productivity, weaken the capacity of institutions to provide essential services, deplete existing resources, and lead to loss of food production as well as capital flight.

Ending these conflicts remains a major challenge for relevant stakeholders. This is partly due to the failure of existing leadership structures and institutions to address development challenges, equitably share resources, and promote peaceful co-existence of all communities in Kenya.

Most individuals elected and/or appointed to serve Kenyans in leadership positions have failed to entrench the principles of fairness and inclusiveness in the distribution of the country’s resources since independence.

While various Kenyan administrative regimes have instituted measures to minimise conflicts, such as the establishment of peacebuilding and conflict management policies, conflicts of varied forms have persisted. It is against this backdrop that this study seeks to explore the nexus between horizontal inequalities and conflict in the context of Kenya.

Horizontal inequalities in Kenya

The following sections discuss the political and socio-economic dimensions of horizontal inequalities in Kenya.

The political dimension of horizontal inequality

The dominant political horizontal inequality in Kenya is the presidency. This is rooted in the conviction that political power offers unparalleled privileges to the president’s ethnic group.

In Kenya, access to this power determines the allocation of socio-economic and political goods. Variations in access to power and the substantial benefits, such as political positions among different ethnic groups, are prevalent in the country.

Rothchild observes that in post-independence Kenya, power-holding elites determine regional variations in appointments for public service and cabinet positions. Since independence, Kenya has witnessed overwhelming political dominance of two ethnic groups out of a total of 42.

This explains the minimal ethnic balance in public appointments. The former and current presidents and the deputy presidents are from either the Kikuyu or Kalenjin ethnic groups, who also form the majority of public servants.

For example, an analysis of a job audit done by the previous administration of the Kenyan Public Service Commission revealed an overrepresentation of Kalenjin and Kikuyus ethnic groups. Out of 214,606 civil servants, Kikuyu and Kalenjin people make up 45,291 (21 percent) and 35,991(16.7 percent), respectively, as of June 30, 2022.

By comparison, the 2019 Kenya Population and Housing Census results reveal that the Kikuyu community is the most populous in Kenya, with a population of 8,148,668 (17.1 percent) in 2019, while Kalenjin people are the third largest community, with a total number of 6,358, 113 (13.4 percent).

However, Article 232 of the Constitution of Kenya on the values and principles of the public service stipulates that the appointment to public office should be fair, merit-based, and represent Kenya’s diverse communities. In terms of senior government positions, the larger ethnic groups share the positions as represented in Figure 1.

The current administration that took up office in August 2022 followed similar trends within the job distribution of public servants. Although the current study is limited in obtaining recent statistics due to the short period that this government has been in power, the results have been visible to the public.

The report also indicates that under the previous government, the majority of heads of state corporations were Kikuyus (36) and Kalenjin (35). This was also reflected in foreign missions, where Kikuyus and Kalenjin accounted for 14 and seven heads of foreign missions, respectively, out of a total of 51. This suggests that the ethnic composition of the public service is primarily associated with the political leadership of the country.

Political horizontal inequalities are predominant among political leaders, and in situations where the degree of inequality is high, leaders incentivise mobilisation on account of group identities.

Perpetuation of political patronage systems alongside ethnic division is one of the key drivers of ethnic-related conflicts in Kenya, as explained in the section below on the nexus between horizontal inequalities and violent conflicts in Kenya.

Socio-economic dimensions of horizontal inequality

The long-standing history of socio-economic horizontal inequalities between ethnic groups and regions in Kenya is largely of geographic and colonial origin. It is noteworthy that these inequalities have persisted over a long period since independence.

The allocation of public goods, such as health and education facilities and physical and water infrastructure, are also determined by access to political power. A report on Kenya’s well-being status points to the continuation of these disparities.

According to the report, the Coast and North Eastern provinces had the highest percentage of Kenyan citizens living below the absolute poverty line, while the Central province had the lowest percentage. In addition, it is also argued that the poverty rate has been increasing over time, not only in the North Eastern province but also in Coastal province.

The British colonial government focused development projects on only selected areas, leaving others underdeveloped. Nairobi, Kisumu, Mombasa, Nakuru, Machakos, Murang’a, Kakamega, Kiambu, Meru, Bungoma, Nyeri, and Kisii benefited from development projects, while expansive areas in some parts of the Rift Valley, North Eastern and Coast were left underdeveloped.

The poverty levels in Mandera, Wajir and Garissa, counties in the North Eastern region of Kenya, stand at 78 percent, 63 percent and 66 percent, respectively, thus ranking among the poorest compared to the other 44 counties in Kenya. This high poverty rate accounts significantly for the high crime and insecurity rate in the region.

Nexus between horizontal inequalities, violent conflicts

Previous research has shown that violent conflicts occurring at global, continental, national and local levels are highly associated with political, cultural, social and economic inequalities. Violent conflicts in multi-racial and multi-ethnic states today remain problematic.

Kenya is no exception. The Kenyan population consists of 47.5 million people, representing over 40 different ethnic groups. The multi-ethnic nature of Kenyan society is susceptible to political polarisation and mobilisation by the political elite with the aim of controlling political and economic resources.

The outcome of such ethnic political mobilisation is an ethnic competition that often ends in ethnic conflicts. A report by ACLED reveals that between 1997 and 2013, Kenya experienced more than 3,500 politically related violent events.

A case in point is the post-election violence witnessed in Kenya in 2007-2008, which was predicated on a weak governance system that was largely ethnised. The violence entailed systematic and targeted attacks on Kenyans on the basis of political affiliation and ethnic group.

Approximately 1,133 people died, no less than 350 000 persons were internally displaced, and approximately 2,000 people became refugees as a result of the violent conflict. Other impacts of the violence included the widespread destruction of 491 government and 117 216 privately owned properties, respectively.

The 2007 general elections were characterised by the idea of ‘forty-one tribes against one’. This saying was coined with the aim of rallying all ethnic groups against the Kikuyu ethnic community. The Kikuyu community was labelled as makwekwe (weeds) or madoa doa (spots) to be removed from the Rift Valley region.

Connected to this, 17 people were murdered and 11 died on the way to the hospital after being burnt in a Kiambaa County church on 1 January 2008. Violence was meted out on Kikuyus by the Kalenjin community.

The immense battle against former President Kibaki in 2007 was built on historic resistance to the perceived dominance of the Kikuyu ethnic community in political and economic sectors in the post-colonial era. The violence symbolised a protest against the persistent marginalisation of the ‘aggrieved’ Kenyans from political power and hence using the opportunity not only to settle tribal scores but also to access resources.

It was widely accepted that it was difficult to separate the perception of the long-term exclusion of Orange Democratic Movement supporters from the political and economic process and the anger they harboured against the alleged rigged 2007 elections. This demonstrates that horizontal inequality between ethnic groups is an important driver of conflict.

Violent conflicts in Kenya have also been witnessed among groups of different economic classes in places like Laikipia County. These conflicts are occasioned by historical land grievances that have remained unresolved for many decades.

Central to the land conflict are ownership, access and use issues among various groups of different economic classes. There exist broad land inequalities that precipitate conflicts among the ranch owners and pastoralists.

For instance, 50 percent of the land in Laikipia County is owned by large-scale ranchers who are believed to be fewer than 30 people in terms of population.

Some other parts of the land have been bought by investors and resold to various stakeholders who are not initial residents, while small-scale landholders have been settled outside conservancies.

Accumulation of large tracts of land by a few rich ranch owners at the expense of the majority, mainly the pastoralists, has resulted in inadequate land for pasture, culminating in violent conflicts manifested in the form of land invasion and wildlife conservancy attacks.

The recurrent conflict in Laikipia County is described as a class conflict between the poor pastoralists and rich ranch owners. Ranch owners have fenced large tracts of land using trenches, locking out pastoral communities using pastures and water points for their animals.

In addition, the ranch owners diverted the flow of the rivers Suguta and Pesis within the farm, as well as destroying established watering troughs and salt licks. This caused water scarcity among pastoralists, a situation that was worsened by drought. Conflicts between ranch owners and pastoralists resulted in the deaths of eight people, destruction of property, and the disruption of social services such as schooling.

There is a strong perception among the pastoral communities residing in the Northeast that they have been historically marginalised by the government. Comparatively, the region falls well below any other parts of the country in terms of infrastructure development, provision of health, and education.

Notably, counties situated in northern Kenya rank last in every human development index in Kenya. Menkhaus, Ken (2015) ‘Conflict Assessment: Northern Kenya and Somaliland’, op. cit. Insecurity characterised by high numbers of violent conflicts in some parts of Kenya, more specifically the North Eastern region, is sturdily linked to deep-rooted forms of political and economic marginalisation, inequality and exclusion.41

Violent conflicts that have a religious dimension are becoming more common across the world, including in Kenya. Violent extremist groups have also exploited Christian-Muslim differences to commit heinous acts. For instance, in 2015, Al-Shabab attacked Garissa University and killed 147 people.

While the country has experienced spates of terror attacks in the past, the worrying and unique factor in the Garissa attack was the fact that those who were held hostage were asked to recite parts of the Qur’an, with the aim of identifying Muslims. It is imperative to note that those who were unable to recite the Qur’an were perceived to be Christians and were killed, while those who recited or dressed like Muslims were spared.

Conclusion

This study has revealed that violent conflicts in Kenya are associated with horizontal inequalities. As discussed above, political, socio-economic, and cultural dimensions of horizontal inequalities have the potential to result or have resulted in violent conflicts in various parts of the country.

In summary, horizontal inequalities are important because of their implications for justice and social stability. Moreover, significant horizontal inequalities in a society are likely to undermine pluralism because they generate grievances between groups and disaffection in society. Therefore, they represent deep historical policy issues that need to be addressed.

Recommendations

- The Government of Kenya should equitably share political and economic goods with all ethnic groups to promote principles of fairness and inclusivity. This will play a critical role in institutionalising and strengthening good political governance.

- With regard to ethnic conflicts, the National Cohesion and Integration Commission should carry out peace awareness campaigns targeting all Kenyans to enhance social cohesion and promote peaceful coexistence among Kenyans. They should educate Kenyans on the different ways politicians exploit their ethnic differences to cause violence and on the benefits of maintaining peace.

- In order to reduce the existing socio-economic inequalities that have resulted in conflicts, while at the same time promoting balanced development, the Government of Kenya should increase financial allocation to the counties that have been historically marginalised and that have high poverty rates and low levels of socio-economic development.

- The Government of Kenya should adopt a whole-of-society approach to conflict prevention in the build-up to future general elections. The government should work with non-state actors, communities, and political and grassroots leaders to ensure peace and political stability prevail before, during, and after elections.

- In response to political inequalities, the Government of Kenya should put in place measures that ensure equal representation of public service appointments by all ethnic tribes. This reduces the perception of discrimination among ethnic communities, more specifically those that emanate from opposition and minority groups.

- In order to successfully deal with land inequalities in Laikipia County, the Government of Kenya should take necessary steps to address historical land injustices and socio-economic situations as a way of bringing lasting peace.

Sylvan Odidi is a Research Fellow at the Kenya School of Government, Nairobi.

This article was first published on ACCORD