Thabo Mbeki Africa Day lecture historically and geographically significant

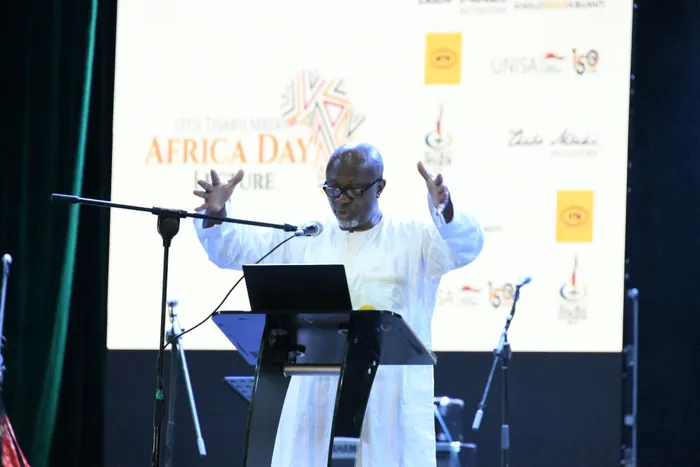

Picture: Facebook/Thabo Mbeki African School of Public & International Affairs – Guinean born scholar Professor Siba N’Zatioula Grovogui presents the Thabo Mbeki Africa Day lecture on May 27, 2023. Grovogui spoke of the symbolic shrinking of Africa, the erasure of knowledge systems, and the nullification of African self-determination. He speaks of a new colonialism where Africans have slowly surrendered their sovereignties, wills, desires, and imaginaries, on the back of choices, obstacles, and handicaps that are often not of African choosing, the writer says.

The decision to deliver the Thabo Mbeki Africa Day lecture in Guinea this year was both historically and geographically significant. It was poignant that on the dusk of Africa Day celebrations, former President of South Africa, Thabo Mbeki, participated in a wreath laying ceremony to honour legendary Guinean liberation leader Amilcar Cabral who had been assassinated in 1973.

Mbeki spoke of Amilcar Cabral as a “leader for all of us” and of how his murderers had wanted to sow divisions among Africans. The former President emphasised the need to forge unity in current day Africa where he argued that strategies of divisiveness continue.

Sixty years after the formation of the African Union, and fifty years after the assassination of Cabral, African unity has been no easy victory and today is still a dream deferred.

Cabral, who had helped lead Guinea from Portuguese colonialism to political freedom, left a powerful legacy, including considerable writings on colonisation, identity, culture, and liberation, which are as resonate in the Continent today as when they were first penned decades ago.

Cabral wrote that “one of the most serious errors, if not the most serious error, committed by colonial powers in Africa, may have been to ignore or underestimate the cultural strength of African peoples”.

But for now, there is no great tower or great power of African culture. Rather, indigenous African culture which could have been an invincibly strong foundation for building unity and development in Africa, has been largely shattered, torn apart and refashioned, misshaped, adjudicated and found wanting against foreign colonial inspired benchmarks. Rather than being given primacy or returned to pride of place, African culture is today not celebrated daily but marked on a single day in western calendars. A form of capitulation, perhaps, to the dominance of colonial cultures. Worse still, culture has become an instrument of division rather than unification.

Cabral had an acute understanding of the destructive seeds of colonialism on the African culturally and educationally. For one, he recognised the potency and poison of colonial education. In 1979, Cabral wrote that “all Portuguese education disparages the African, his culture and civilisation”. “African languages are forbidden in schools. The white man is always presented as a superior being and the African as an inferior.” He proposed a process of “re-Africanisation” as a necessary antidote to systemic de-education and de-culturing.

“Re-Africanisation” was a call for African elites to cast off the robes and rewards bestowed on them by colonialism and re-fashion their consciousness on authentic African culture, values, and knowledge systems. This, Cabral, argued would reignite African purpose and prosperity. He wrote, “A people who free themselves from foreign domination will be free culturally only if, without complexes and without underestimating the importance of positive accretions from oppressor and other cultures, they return to the upward paths of their own culture, which is nourished by the living reality of its environment, and which negates both harmful influences and any kind of subjection to foreign culture.

“Culture” Cabral wrote, “is simultaneously the fruit of a people’s history and a determinant of history.”

The issues of culture and sovereignty were a key theme in the very powerful Thabo Mbeki Africa Day lecture presented by Guinean born scholar Professor Siba N’Zatioula Grovogui.

“I am here today to look inward and call to attention greater threats ahead than before. These too are related to the inequalities of the structure, mechanisms, and processes of the world of nations, states, capital, and cultures,” Professor Grovogui began.

In his lecture, the Professor spoke of the symbolic shrinking of Africa, the erasure of knowledge systems, and the nullification of African self-determination. He speaks of a new colonialism where Africans have slowly surrendered their sovereignties, wills, desires, and imaginaries, on the back of choices, obstacles, and handicaps that are often not of African choosing.

He spoke of how many African scholars “inhabit disciplinary trenches from which they write in and for journals set up mostly in the West, whose concerns do not always accord with the temporal exigencies of Africans”.

His lecture sets out a clear picture of the lingering legacy of colonialism, where culture and sovereignty were extracted alongside minerals and other wealth. Cabral’s notion of re-Africanisation is indeed necessary to regenerate a mindset free of colonial erosion and extraction, and forge a future based on sovereignty and self-determination.

The Thabo Mbeki Africa Day lecture took place in a Guinea that is far from perfect. The sight of the former President of South Africa, accompanied by the Guinea military, was a pictorial spectacle of the omnipresence of the country’s military might, and Guinea’s culture of governance. Although Guinea has never had a war it has a long history of coups and unrest.

Just weeks after he had led a coup against President Alpha Conde in 2021, Colonel Mamady Doumbouya was to become Guinea’s interim President. The young soldier justified the military coup as a legitimate and necessary means to end government corruption, mismanagement, and human rights abuses by President Alpha Conde.

Announcing the coup, Doumbouya told the people of Guinea, “the Guinean personalisation of political life is over. We will no longer entrust politics to one man, we must entrust it to the people”.

While at first, citizens celebrated openly about the coup, and the fall of Conde, joy was short-lived as yet another regime began to stray from its promise and promises. Two years later, Doumbouya is still at the helm of the country as an interim leader. For now, the country is still caught in the tightrope of uncertainty. Just this month, there were anti-government protests against frustrations at poor delivery and unrealised expectation from the interim government. Reports show that at least seven people were killed in the skirmishes, and over 30 injured between citizens and security forces. Doumbouya’s military government has now banned all public demonstrations, a direct contradiction of his ‘will of the people’ utterances.

Five decades after the death of Cabral, the Africa he longed for and lost his life for is not yet born. There is a surrender of sovereignty and culture. The soul of Africa is lost and yet to be found. Cabral once wrote “we must act as if we answer to, and only answer to, our Ancestors, our children, and the unborn”. Perhaps if this was to become the Continental anthem of Africa, the cultural strength of Africa would be the unconquerable force of which Cabral spoke.

Kim Heller is a political analyst and author of ‘No White Lies: Black Politics and White Power in South Africa’.

This article was written exclusively for The African. To republish, see terms and conditions.