Social media misinformation during election season

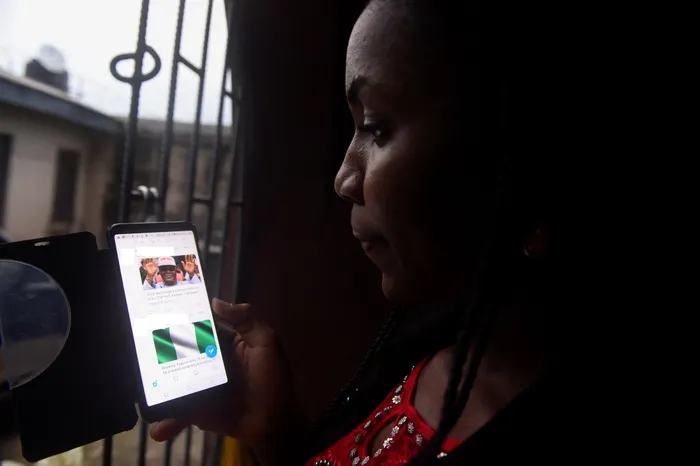

Picture: AFP – Nigeria goes to the polls on February 25. According to the Independent National Election Commission of Nigeria, misinformation on social media is a real problem. The Institute for Security Studies also says that, with growing access to social media in Africa, there had been evidence of such platforms being weaponised in political spaces.

By Vhonani Petla

This year is a significant year for several democracies in Africa. Countries, including Nigeria, will be taking to the polling stations for their presidential elections.

With the Nigerian elections just a few weeks away, there is much attention on the country. The elections have been described as crucial for Nigeria’s democratic history. They are the first elections under the new electoral legislation, which was signed into law in February last year. The elections also come at a time when Nigerians are dissatisfied with the socio-economic standing of the country, and the government’s failure to remedy the issues.

A poll showed that 77 percent of the population were dissatisfied with how the government has been failing to improve livelihoods, which have been deteriorating, and failing to curb corruption. Hence the hope that new leadership will restore the people’s faith in the government. With more than 11 million new voters registered, there is no question about how desperate the citizens are for change. While the Nigerian government and the Independent National Election Commission (Inec) of Nigeria are confident about the work they have put into issues like vote-rigging which often delegitimises elections, there is much anxiety over the issue of social media during elections.

The Inec commissioner has argued that social media is a real problem in Nigerian elections. The Institute for Security Studies also argued that, with growing access to social media in Africa, there had been evidence of social media being weaponised in political spaces. The use of social media in election campaigns and their success dates from Barack Obama’s 2008 success in the US elections. However, in recent years, evidence from other countries, as well as Nigeria, has shown that social media is a double-edged sword.

This can be seen through the spread of misinformation on the platforms or smear campaigns, for example, the #WithdrawIsko in the Philippines elections. The Kenyan elections last year saw misinformation via social media being used to reduce voter turnout to compromise the electoral process. In Nigeria, the elections are set to take place on February 25.

However, by the end of last year, there were suspicions of foul play on social media, the most popular being bots. Bots, short for robots, refer to software that performs automated pre-defined tasks. These are favourable as they carry out tasks faster, more accurately and at a higher volume than humans. There are bots used for good, however many bots are used dishonestly.

The Centre for Journalism Innovation and Development has shown that hashtags like #BATified, #Obidient, #Atikulated and #kwankwasiya related to the presidential candidates were bot operated. Furthermore, evidence from an analysis carried out using botsight tools found that more than a million bots followed the electoral candidates on Twitter.

The implication of the bots and other artificial intelligence (AI) tools used on social media to spread misinformation is that they undermine the principles of democracy. Democracy ought to be built on free and fair elections; however, the AI tools take this away. Furthermore, the content from the bots and other AI tools, like deep fakes, also has the potential to fuel political conflict which, in some instances, has caused violence. It is evident from the above that besides defeating the whole point of elections and democracy, AI, through social media, also has the potential to stir violence.

The question then is: What have the social media companies done to mitigate the risk that AI poses with misinformation? In answering this, it is important to acknowledge that there have been some measures in place; however, there is a long way to go in fighting the dangers caused by misinformation. This could include the countries increasing the number of people allocated to moderate social media content and making them as diverse as possible. For example, African countries are diverse and have many languages. The moderators and tools used must be able to deal with this. For the Nigerian elections, META (Facebook’s parent company) is said to have hired 70 fulltime staff to work on the upcoming election. However, in Nigeria, which has about 150 million internet users, 70 staff will probably not be enough to moderate such a large pool of posts. Undoubtedly, media monitoring is challenging in a country like Nigeria, with its more than 250 languages and the moderators being familiar with only four – Igbo, Yoruba, Hausa, and Pidgin. What does this mean for the content and misinformation that might come from the bots, deep fakes, or other tools in the other languages that the moderators and tools are unfamiliar with?

This demonstrates the need for more work and investment in curbing misinformation. Organisations like Africa-Check have taken it upon themselves to verify information and flag misinformation that might be on social media regarding the elections. It is important that for the sake of the legitimacy of the elections, such platforms are made accessible to people so that they can verify the information on social media, as highlighted that much of it comes from bots, deep fakes or unreliable sources on social media. The importance of a high volume of staff and tools in content moderation is playing out in the January 8 events in Brazil.

Researchers have argued that the algorithm on Facebook and Tiktok is responsible for steering people towards baseless accusations, false claims of election fraud, and extremist content. Hence the events that took place in Brazil on January 8. This highlights the need for adequate content moderation from these social media companies, especially in elections where emotions run extremely high, and any piece of misinformation can lead to violence.

This then justifies the growing anxiety over the events at Twitter. In the past couple of months, there has been an easing of content moderation, the firing of staff, particularly in the African office, and harmful accounts that had been banned from the platform being brought back. This raises questions about the platform’s ability to be impartial and prioritise making the platform free of misinformation and harmful content.

It is time for African countries to consider digital literacy for organisations, governments and citizens. This will empower them with skills to verify the information and be knowledgeable on artificial intelligence so that they are not quick to believe everything they encounter.

It is time for African governments to be aware of the risks and challenges associated with artificial intelligence and try to mitigate them. Africans must invest in research and adequate digital literacy that allows them to understand how the digital world works and be able to adapt accordingly. The need for this is not limited to elections only. Misinformation can be spread around any other issue within the country, hence the need to have digital literacy as a priority.

Vhonani Petla is a junior researcher, Digital Africa Research Unit, Institute for Pan African Thought and Conversation at the University of Johannesburg.