Progressive leaders emerge amid less favourable forces

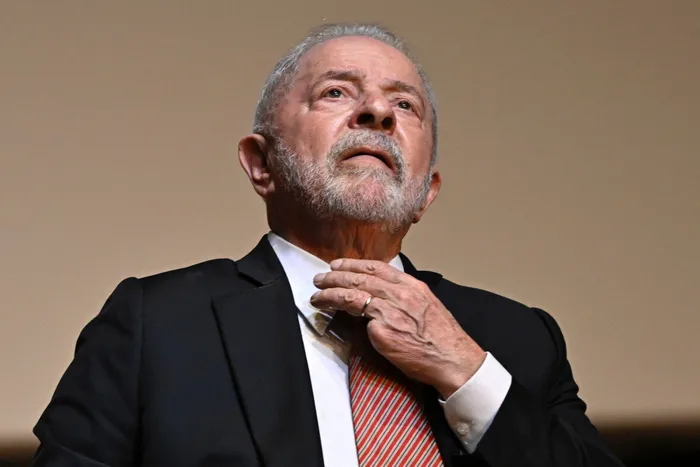

Picture: Mauro Pimental / AFP / February 6, 2023 – Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva gestures during the inauguration ceremony of Aloizio Mercadante as President of the Brazilian National Economic and Social Development Bank (BNDES) at the BNDES headquarters in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

By Miguel Enrique Stedile

This century that has been, and will continue to be for a long time, marked by the geopolitical dispute between the US’s attempt to maintain hegemony and China’s rise, which is shielded by Russia.

Latin America and the Global South, however, occupy a central role because of their resource wealth, which is the object of the desire and greed of “green capitalism”. Political control over this territory implies easy access to agricultural products, minerals, and hydrocarbons converted into commodities.

The first progressive wave, which began with the victory of Hugo Chávez in Venezuela in 1998, was characterised by regional integration and geopolitical sovereignty that removed the continent as a satellite of the US.

The Unarsu (Union of South American Nations) and Celac (Community of Latin American and Caribbean States) diminished the power of the traditional OAS (Organisation of American States), retrieving Cuba from political isolation imposed by the US.

The second decade of the 21st century was marked by a counter-offensive by the US. The US supported, publicly or discreetly, movements to weaken and overthrow these independent and proud Latin American governments, even if they played within the limits of capitalist institutionality and reformism.

Thus, different anti-democratic actions were used in the continent such as parliamentary coups (Paraguay and Brazil), traditional military coups (Honduras), hybrid wars (Venezuela and Bolivia) and the constant and intensive use of lawfare by the judiciary and by parliaments and industrialists, given the subordination of elites in Latin America.

This “second wave” of progressivism emerges in a scenario of less than favourable external and internal forces. And as the presidents of Chile and Peru (Gabriel Boric and Pedro Castillo) know very well, electoral victories are not necessarily political victories in their entirety.

The new leaders came to power with complex, young and often fragile alliances, some of them with rightwing sectors, such as Luiz Inácio “Lula” da Silva’s candidacy. Alliances that are weakly formed or are not formed around programmes, carry with them tensions and contradictions between different forces.

There are also the contradictions that the progressive “first wave” was not able to overcome, as the Cuban intellectual Fernando Heredia reminded us: all advances are reversible; world capitalism is hypercentralised, financialised, parasitic and destructive, and can only live if it continues to be so and the exploitation and domination of Latin America are necessary for the maintenance of US imperialism.

Therefore, Lula will discover a very different scenario from the one he left at the end of his second mandate. His election aroused expectations and hopes throughout the continent. Lula still contends with the internal devastation and dismantling of the state, in all areas, as well as a global recession on the horizon and the return of hunger to the country.

It is still unknown how resilient the far-right opposition mobilised by the remnants of Bolsonarism will be, but the riots of January 8 signal an active opposition. Even without the support of the Bolsonaro government, what will be the behaviour of the extreme right in Latin America, since it is highly internationalised, ideologically and financially?

The new Brazilian government faces the prospect of both the global economic and climate crises. In both cases, Lula’s administration needs to build alternatives that do not punish the poorest and do not take place within the ineffective framework of “green capitalism”. Not to mention that Brazil and Latin America will be pressured to choose “co-existence” with the US or co-operation with China.

The Brazilian left, as well as its Latin American counterparts, has the challenge of understanding the deep transformations in work in peripheral countries and the changes in the organisational, cultural and ideological configuration of the working class, from production and precarious work to the advance of religious fundamentalism.

And, again and permanently in leftist governments, the tension between time and the limits of the state will confront the urgency and the need for structural changes demanded by popular movements. The people must be the subject of the transformations and clashes, to understand these limits not in a passive way, but as a tool to accelerate them.

The progressive processes in Latin America are often personified in the trajectory of their leaders. Lula, Cristina Kirchner, and Andrés Manuel López Obrador are examples of personalities that go beyond the limits of their organisations and political fields, that assume the roles of spokespersons for the projects they represent, but, at the same time, may collaterally replace organisations in the dialogue with the population or be too responsible to make the decisions to conduct these processes individually.

What the Latin American progressive “first” and “second wave” have in common is the conviction that in this scenario of geopolitical dispute and global economic crisis, there are no individual ways out.

It is only possible to place oneself in a sovereign position by acting in regional co-operation, recovering the mechanisms of integration and solidarity, behaving as a cohesive bloc, based, not on pragmatism, but on a historical project of autonomy, independence and political, food, energy and ecological sovereignty.

And, primarily, sustained by a permanent organisation and popular mobilisation.

Miguel Enrique Stedile is a member of the coordination of the Tricontinental Institute for Social Research

The article was published in Peoples Dispatch