‘No go’: UAW president rejects Stellantis wage increase offer

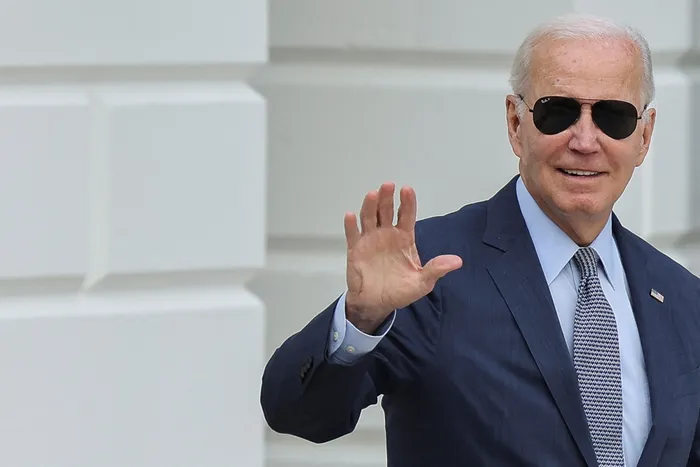

Picture: Kevin Wurm/REUTERS/August 11, 2023 – With presidential elections in the offing, President Joe Biden has given his support to striking motor industry workers, saying ‘the automakers should match their “record corporate profits” with “record contracts” for workers, the writers report.

Picture: UAW via Twitter – About 12,700 UAW members went on strike Friday, demanding pay increases and more-equal treatment and benefits for temporary workers, who have seen their pay lag behind full-time workers for years, the writers say.

By Gerrit De Vynck and Lauren Kaori Gurley

The president of the United Auto Workers on Sunday rejected a public offer by Jeep parent company Stellantis to boost pay 21 percent over four years, pushing a historic, co-ordinated strike against the nation’s three biggest carmakers into a third day.

Stellantis, which is based in the Netherlands and was formed in 2021 through a merger of Fiat Chrysler and France’s Peugeot, said Saturday that it had offered the union a “highly competitive” 21 percent wage increase. The union said it had “reasonably productive” conversations with Ford on Saturday and was planning to meet with GM as well. Both of those companies have offered 20 percent raises over four years.

But on Sunday morning, UAW President Shawn Fain said that Stellantis’s 21 percent offer and other terms presented by the automakers aren’t sufficient and that the strike will continue.

“That’s definitely a no go,” Fain said on CBS’s “Face the Nation”. He added: “We’ve asked for 40 percent pay increases. And the reason we asked for 40 percent pay increases is because in the last four years alone, the CEO pay went up 40 percent.”

About 12,700 UAW members, or 8 percent of the union’s autoworkers, went on strike Friday, demanding pay increases and more-equal treatment and benefits for temporary workers, who have seen their pay lag behind full-time workers for years. It’s the first time the UAW has gone on strike against all three of America’s biggest automakers at once.

The strike comes as unemployment in the United States is at historic lows, but fallout from the pandemic and higher inflation have boosted worker anxiety. Companies have continued to post profits and increase executive pay, and the autoworkers are among a broad resurgence in union activity in the United States as workers from nurses to Hollywood script writers and actors seek better pay and job security.

Although the UAW strike affects only a handful of plants, Fain said the union was prepared to do “whatever we have to do” and expand work stoppages. “If we don’t get better offers and we don’t get down to taking care of the members’ needs, we’re going to amp this thing up even more,” Fain said.

‘Record profits’

Fain’s comments tempered any hope generated by the Saturday negotiations of a swift resolution. The union is asking for a 36 percent raise over four years, a four-day workweek, defined-benefit pensions and company-financed healthcare in retirement. The automakers have countered that their offers to the union are among the best in history, but that they can’t meet all their demands while still remaining profitable.

A spokesperson for Stellantis said the company would resume bargaining with UAW on Monday. Spokespeople for Ford and GM did not return requests for comment.

“It’s all of our hope that it will end sooner rather than later. But record profits have been generated,” said House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries (NY), who was travelling to Detroit on Sunday. “It’s only fair that everyone share in those record profits in the prosperity that has been created.”

Over the weekend, workers gathered on picket lines at the plants where UAW had kicked off the strike. Spirits were high as supporters brought supplies and honked their car horns in solidarity. “We want to become middle class again,” said Andrew Hudson, a striking production worker outside Ford’s assembly plant in Wayne, Michigan, where the company makes Ranger trucks and Bronco SUVs.

A few weeks ago, Hudson reached Ford’s top pay rate, $32 an hour, but it took him six years to get there. He’s on strike mostly because he doesn’t want his newer colleagues to have to wait that many years to get the top pay like he had to, he said. “We can’t experience the American Dream that so many autoworkers before us, like my grandfather, got to,” said Hudson, whose grandfather was able to own a house and two cars while putting his kids through college on an autoworker’s salary. By contrast, Hudson said he and his co-workers are “struggling” to do the same on their own salaries.

Nicholas Harvey, 33, a single father who works in material handling, said he was on strike for higher pay. At $24.85 an hour, he said he had to move back in with his parents after his split with his wife. “This used to be a coveted job,” he said. “But I’m paycheque to paycheque. I want to own a house, put money away for [my kids’] college, but it’s hard saving.”

Battleground states

Meanwhile, the spectre of the presidential election hovered over the strike, as politicians from both parties weighed in. President Biden and former president Donald Trump, the leading front-runner in the Republican contest, have taken contrasting approaches, with Biden saying the automakers should match their “record corporate profits” with “record contracts” for workers and Trump criticising the UAW president. Biden said Friday he was sending two of his senior advisers to offer help in getting a deal done.

The Midwest states where auto plants are traditionally concentrated, including Michigan, are expected to be key battlegrounds in the 2024 election. But Representative Debbie Dingell, Democrat-Michigan (D-Mich) cautioned on Sunday that politicians should keep their distance. “I do not believe that the president should intervene or be at the negotiating table,” Dingell told CBS.

For his part, Fain has said another Trump presidency would be a “disaster”, but he has held off from endorsing Biden, saying the president must earn his self-styled moniker of the “the most pro-union president” in history.

Trump and other Republicans have criticised Democrats for pushing the country toward electric vehicles, many of which are not built in the United States. Democrats have said the companies need to consider their workers while pushing the transition to more climate-friendly cars. Chinese companies like BYD currently dominate the global electric vehicle market, and even US companies like Tesla order their batteries, the key component of an electric car, from foreign manufacturers.

“Anyone that doesn’t believe global warming is happening isn’t paying attention,” Fain said Sunday. “But this transition has to be a just transition. As it stands right now, the workers are being left behind.”

The Big Three automakers have been ramping up their design and production of electric vehicles as Americans’ interest in buying the cars continues to grow. But a major strike could get in the way of that transition, and the traditional automakers’ ability to catch up to foreign competitors and electric-only producers like Tesla, said Dan Ives, an analyst with Wedbush Securities.

“A long and nasty strike … would be an absolute debacle for the Detroit Three,” Ives said. Any delay in ramping up their electric vehicle production will stand to benefit Tesla, which has been facing increasing competition from the traditional automakers, he added.

Lauren Kaori Gurley is the labour reporter for The Washington Post. She previously covered labour and tech for Vice’s Motherboard. Gurley reported from Wayne, Michigan. Gerrit De Vynck is a tech reporter for The Washington Post. He writes about Google, artificial intelligence and the algorithms that increasingly shape society.

This article was first published in The Washington Post