Madiba’s long walk to freedom should not be in vain

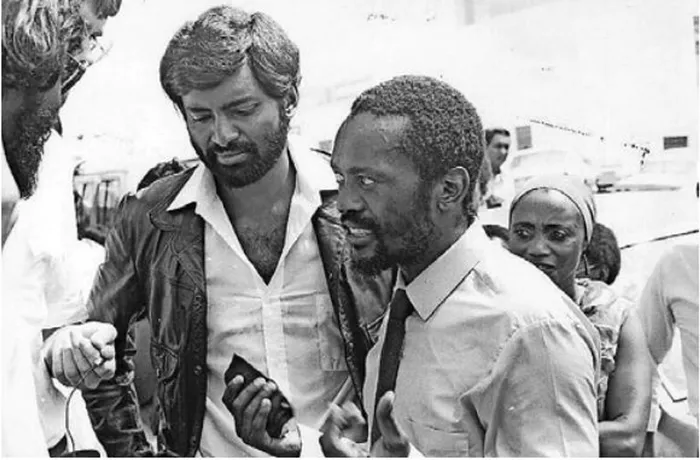

Black Consciousness activists (from left) Strini Moodley, Saths Cooper and Aubrey Mokoape, launched the SA Students Organisation (SASO) with Steve Biko. The trio were jailed for treason as a result of their activism. – Picture: Independent Media Archives

Nelson and Winnie Mandela salute the crowd outside the Victor Verster Prison following his release on February 11, 1990. – Picture: AFP

On February 11, 1990, South Africa's first democratically elected President, Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela, was released from prison. Today marks the 34th anniversary of that epoch-making moment in history when the world joined millions of South Africans to welcome him back home. Black Consciousness Movement leader Prof Saths Cooper, who spent time with Madiba while they were imprisoned on Robben Island, reflects on Mandela's leadership in prison, the role he played in ushering South Africa's transition to democracy and why the sacrifices made by his generation should inspire all South Africans to reclaim the country’s democracy project.

By Saths Cooper

Today marks the release from imprisonment of Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela (Madiba) 34 years ago. Arrested on August 5, 1962, in Howick, and sentenced to hard labour that November for incitement and leaving the country illegally, he was first imprisoned on Robben Island on May 27, 1963.

On October 9, 1963, he was joined with the other founders of Umkhonto we Sizwe – the real MK – in the famous Rivonia Trial. On June 12, 1964, Madiba, Walter Sisulu, Govan Mbeki, Raymond Mhlaba, Ahmed Kathrada, Dennis Goldberg, Elias Motsoaledi and Andrew Mlangeni received life sentences. All but Goldberg joined numerous other political prisoners on Robben Island, some sentenced to “natural life”, and some who had been there since 1961 – The Stellenbosch 21 – and Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe, who was kept in virtual solitary confinement from May 3, 1963, to May 4, 1969.

I got to know and interact with the Rivonia trialists intimately from October 1977, till the end of March 1982, when he, Sisulu, Mhlaba and Mlangeni were removed to Pollsmoor Prison. A few days later, the remaining SASO/BPC trialists and I – Muntu Myeza, Patrick Lekota, Aubrey Mokoape, Pandelani Nefolovhodwe and Nkwenkwe Nkomo – were removed to Victor Verster Prison, from where Madiba was released on February 11, 1990.

Madiba’s perspicacity was demonstrated the very next day after the late Aubrey Mokoape, the late Strini Moodley and I were removed by the then Cape Town Supreme Court from isolation into his cell block. Madiba mentioned an incident involving the late Neville Alexander where the latter was accustomed to use first names that had apparently caused resentment amongst peasant inmates. This was Madiba’s way of informing us that he preferred to be called Madiba, although we had used the respectful ‘Ntate’ (Sesotho/Setswana for a male elder). He probably foresaw that as we were urban university-student types – I was 26, the age that he joined the ANC – we could lapse into using first names.

Our respect for him and the older prisoners and our disquiet with using clan/tribal names, resulted in our continued usage of ‘Ntate’ until it simply became Madiba. The generational and political gaps were obvious, and it was much easier to overcome the former. We naturally accorded Madiba and the older comrades the respect that we were wont to afford our elders, which was part of our upbringing, and indicated to them the many ways in which we perceived the world differently, which Madiba and many of the older leadership acknowledged.

The political differences were much more difficult to resolve. The source of tension was the post-June 1976 aftermath, which resulted in the largest influx of political prisoners in the history of Robben Island. Indeed, it was only in January 1977 when the high walls [came down]. This portended a ripe recruitment opportunity for the older sections of the liberation movement, which were largely comprised of middle-aged members. Initially, the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC) attempted to avoid recruitment, because of its inherently divisive nature, but the ANC had no such qualms.

Madiba and Walter Sisulu – the ANC Liaison with the Black Consciousness Movement (BCM) – decried this situation and only when the BCM had dwindled in size around 1980 did they sign a non-recruitment pact. The PAC, then feeling that it had lost out in the numbers game, baulked at signing.

The major political difference between the ANC and us in the BCM was the ANC’s four nations hypothesis; that Africans, Coloureds, Indians and Whites comprised the four spokes that emblazon the ANC wheel. We held that all blacks were oppressed by a phalanx of white racist power and privilege that was apartheid and that our unity as blacks in opposition to apartheid was paramount.

In our first encounter that chilly spring afternoon in 1977, he also invited us to discuss with him when his exams were over (the SASO/BPC trialists were denied study privileges) the question of when it was appropriate for a liberation organisation to open its membership to other races. Our response was that the ANC had taken such a decision at one of its conferences in Tanzania and that our BCM was founded on the testimony of all blacks – Africans, Coloureds and Indians – working together in the same formation to actively oppose apartheid. We never traversed this topic again. In many ways, the ANC in Robben Island was different to the ANC outside those prison walls, as most of the information only reached prison much later. The natural tendency in most people – and politicos are no exception – is to retain understandings with which we are familiar.

Although he initially could not understand the birth and growth of the Black Consciousness Movement, he soon began to appreciate our standpoint and accepted the definition of ‘black’ as essentially embracing all those who were not white. I never heard him use the pejorative ‘non-white’ after October 1977. Thus, it perhaps is that our democracy relies on this generic description of blacks (eschewing the narcissistic and demeaning term ‘non-white’), as opposed to privileged whites who had generally enjoyed and benefited from the previous apartheid system.

We asked for and got a meeting with all the Rivonia trialists a few days later to make known our strong reservations about their impending meeting with George Matanzima and members of the Transkei Cabinet, concerning their possible release as part of the Transkei Homeland Independence celebrations. This we did the following day, amidst intense but cordial questioning. The meeting with Matanzima was aborted, and the Transkei anniversary celebrations went ahead without anyone being released from prison. I often wonder how someone who had been in jail for some 15 years, with the harsh prospect of serving life imprisonment would have felt of black hotheads who put principle above all else.

Madiba’s initial impression of me as a radical hothead was probably tempered over time and through various interactions of a social, sport and political nature. We used to share early morning runs around the tennis court, have regular tennis matches, and I even learnt to play dominoes which he loved to play almost daily after lunch. He would often share personal and political information and felt obliged to inform the leadership of the various political organisations of any developments that may impact them. He was adamant that all our organisations had been infiltrated by apartheid agents; this the record confirms. Yet some of his fellow trialists could not accept that Gerhard Ludi (an apartheid agent) had infiltrated Rivonia.

There was no rancour in any of our dealings with Madiba and the older ANC leadership, despite the periods of intense tension caused by the recruitment already alluded to. Our engagements were always cordial and grew to an easy camaraderie and deepening mutual respect. Disagreements on political positions never degenerated into acrimony – which was quite rife with the influx of hundreds of post-June 1976 youth into the rest of Robben Island – but always ended with us agreeing to disagree. This is something that our polity sorely lacks, as is seen in our tense and violence-prone political discourse.

From the time that I first met him in those miserable conditions in prison till the time of his recent illness he exuded a regal demeanour and carriage that infused respect amongst all who came into contact with him. A stickler for custom and pleasantries, he dictated the pace of the ensuing interaction, by careful listening, usually without interruption, and then presenting how he saw the way forward. Very few could refuse to take tea with him, by which time any anger and rancour had dissipated.

When he had made up his mind about a position, he was committed to it, despite the howl of protests from others around him. But if you could convince him that his position was flawed, he would not hesitate to acknowledge this. In this way he was able, for example, to move white racists in our midst to accept the inevitability of peaceful transformation in our country. And he led by example, making extraordinary concessions to reconciliation which, unfortunately, some in our country have taken for granted, ignoring the massive exploitation, oppression and suffering wrought by the erstwhile apartheid system.

During his presidency of our country, he was magnanimous to many of his detractors within the ANC who, if they had been in power, may not have been as generous. He went out of his way to accommodate numerous former prisoners from across the political spectrum who owe their positions to his ability to rise above partisanship. Beneficiaries of apartheid owe him a particular debt of gratitude for his reconciliatory approach that has permitted them to continue with their enterprises and positions, in most cases reaping unimaginable profit and personal benefit.

Since his release from prison, his accession to political power as our nascent democracy’s Founding President and his retirement, my interactions with him were infrequent. I avoided being intrusive. When we did meet, it was always with great fondness and he had the knack of saying the right thing, whatever the circumstances, especially to those I was with, whether family, friends or colleagues. This quality will endear him to all those people that he has interacted with in South Africa and abroad. Each will have their memories of being touched by a ‘saint’ in his lifetime.

Madiba was the first to disavow that he was a saint, but he was far from being a sinner either. There will be other occasions to dissect his foibles. Now is the time for South Africans to acknowledge the debt of gratitude that we owe to his singular contributions. Pity it is that there will be constant squabbling about his legacy. He deserves better. Unfortunately, greatness in public life is not a guarantee of equanimity in private life.

His ability to relate to all sectors of society, his sense of humour and quiet dignity has endeared him to people all over the world who have had the fortune to interact with him. History will record in detail his role in shaping our country. His lengthy illness has allowed most of us to grieve and accept his passing. It’s now time to celebrate his life and times that we have been so much a part of and ensure that what he and we have struggled for will not be in vain.

When we celebrate the 30th anniversary of our freedom on April 27, we would have been bombarded by the claimants to our liberation history and the hundreds of other parties who would:

- Pretend to carry through on the promise of liberation, which in nearly every public sector we seem to be failing;

- Wish to deny, diminish, ignore, or bad-mouth what was an essential life and death struggle for the freedoms that we do enjoy, while daily survival often intervenes, dimming even the best of memories of our terrible, murderous past, making us doubt that there was such a struggle;

- Want us to simply “get over” ourselves;

- Want us to just join them, in their quest for power, privilege, and position.

Indeed, the only visible growth area is in politics; all at our expense. Ego, jargon and all manner of sleight of mouth and hand are afoot. Sitting at SONA on Thursday night, it was impossible to avoid the dignified, often stirring, and largely visionary and factual portrayals by presidents Mandela and Mbeki. There was unparalleled dignity, undoubted and capable leadership.

While we may have disagreed with them, they did take us to great heights, restoring our impugned individual and collective dignity and respect, cohering as a people and holding our own across the globe. We were not a bedlam of languages, ethnicities, beliefs, and factions. There weren’t the hordes of hangers-on and praise singers, the strings of blue lights, and the orgy of self-serving and aggrandisement. Madiba particularly was not afraid of people and actively sought out children and youth, many of whom he tried to cultivate, as he did with President Ramaphosa.

Importantly, he committed to and only served one-term. Now, that may be a topic for another time: What if he had served another term, consolidating the immense gains made in mother-child health, education, and good governance, encouraging criticism, not foisting fawning fans on us, never eschewing or outsourcing his responsibilities to the country, its growth, its redevelopment and the redistribution of economic wealth, that increased independence and sustainability.

What we lost we cannot regain, but we can exercise our critical faculties to realise that the power lies with us. There is no Mandela who will be our saviour. Our salvation lies in our minds (to think and act positively on that thinking, away from the doom and gloom that can so easily engulf and consume us from acting to make things and change happen) and in our hands.

Prof Saths Cooper is the President of the Pan African Psychology Union, a former leader of the Black Consciousness Movement and a member of the 1970s group of activists.

This article was written exclusively for The African. To republish, see terms and conditions.