Jury out on youth league’s quest for independence

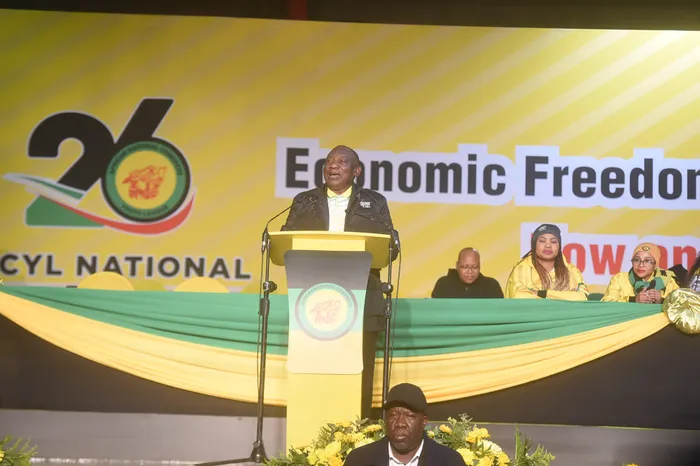

Picture: Itumeleng English / African News Agency (ANA) / July 2, 2023 – President Cyril Ramaphosa speaking during the 26 ANCYL conference at the Nasrec Expo Centre, Johannesburg. Among the developments that have characterised Ramaphosa’s presidency is the weakening of the ANC’s leagues, the writer says.

By Bheki Mngomezulu

President Cyril Ramaphosa’s ascendance to power was not smooth from its very inception. Firstly, during the ANC’s elective conference in December 2017 in Nasrec, something unprecedented in the history of the ANC happened. Nkosazana Dlamini Zuma gave Ramaphosa a good run for his money. No woman had contested an ANC leadership position at this level.

As the campaign gained momentum, there were clear signs that Dlamini Zuma was in a better position to win the race. It was only at the 11th hour that David Mabuza, then premier of Mpumalanga Province, handed the presidency of the party to Ramaphosa on a silver platter, using what he called a “unity vote”.

Even then, Ramaphosa won the election with a very narrow margin of only 179 votes – something that had never happened in the ANC before. Second, Ramaphosa took the baton from his predecessor, former president Jacob Zuma, under controversial circumstances. He ascended to power on February 15, 2018, after the ANC had forced Zuma to resign on February 14. Unlike when former president Thabo Mbeki was forced to vacate office under the same conditions in September 2008, and Kgalema Motlanthe became the caretaker president, this time around, Ramaphosa jumped in immediately to complete Zuma’s term as president of the country.

In 2019, the ANC won the election once again. This meant that Ramaphosa was now officially expected to assume his first term in office. Hypocrisy, dishonesty, and a lack of consistency in the ANC played a critical role in giving factionalism in the party a fresh impetus.

One of the resolutions of the ANC in 2017 was to push for radical economic transformation (RET). After the conference, some in the ANC abandoned this policy position as they did many other resolutions. Those who were honest and loyal to the party insisted that RET should be on the ANC’s agenda. When no consensus was reached, the party loyalists were labelled as the “RET faction”, while the other group became known as the “CR 17” faction – later referred to as the “Ankole”.

Surely, none of these groups are enshrined in the ANC’s constitution or any of its official documents. But the reality is that activities in the ANC, including the appointment of officials and the election of members into office, have been shaped by these informal factions. Elections are no longer fair, and they are devoid of any rationality. Among the developments that have characterised Ramaphosa’s presidency is the weakening of the ANC’s leagues.

The youth league (ANCYL), women’s league (ANCWL) and the MK Military Veterans League have all been non-existent for some time. This has dented the political image of the ANC and has negatively re-written the party’s history.

The party’s leagues are expected to represent the ANC among different constituencies. Their absence leaves a political void. Lately, in the aftermath of the ANC’s provincial elections and the 2022 national election, where Ramaphosa won his second term, the RET faction has been neutralised. This is evidenced in the expulsion of both Carl Niehaus and Ace Magashule and the loss in elections of many of those who are linked to the RET faction.

The dominance of the other faction in both the party’s national executive committee (NEC) and the national working committee (NWC) attests to this assertion. It did not come as a surprise that, when the Phala Phala issue was debated in Parliament, it was dismissed by the majority of ANC MPs. Even the report of the Section 89 three-member panel, which was led by former chief justice Sandile Ngcobo, was abruptly shot down.

These incidents put it beyond doubt that Ramaphosa was on an upward political trajectory. Something worth noting is that when Ramaphosa could no longer stand the mounting heat caused by the Phala Phala matter, he decided that he was resigning on November 21, last year – which was the right and noble decision meant to protect the integrity of the party and the country.

However, those who surround him could not let this happen. They convinced Ramaphosa not to resign. They did not do this for the love of the country or the ANC. Instead, they did it for their own self-aggrandisement but to the detriment of both the ANC and the country. This incident boosted the president’s confidence level but tarnished the ANC’s image. After over eight years, the ANCYL eventually elected its new leadership. During July 2023, the ANCWL is also set to elect its new leadership. If the Veterans League regains its former glory, this would bring stability to the ANC. The resurgence of the leagues and the neutralisation of the RET would increase prospects for ANC unity under Ramaphosa.

Prof Bheki Mngomezulu is Director of the Centre for the Advancement of Non-Racialism and Democracy (CANRAD) at the Nelson Mandela University