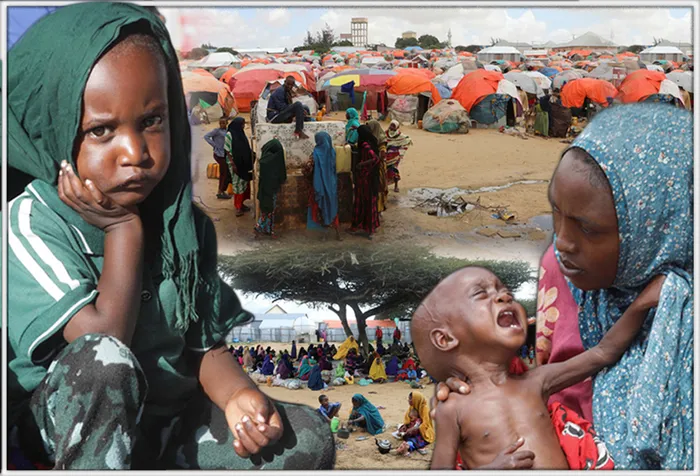

Dire challenges for children in Africa

Graphic: Wayne Geduldt African News Agency (ANA) – The shocking new evidence of low learning outcomes is devastating for Africa. It makes one question whether the education system on the Continent is relevant to the needs of the 21st century.

By Edwin Naidu

As matrics in South Africa brace themselves for the final countdown towards their school exit, according to a damning new report, children in Africa are five times less likely to learn the basics.

The shocking new evidence of low learning outcomes is devastating for Africa. It makes one question whether the education system on the Continent is relevant to the needs of the 21st century.

The relevance of matric, for example, in South Africa, has often been questioned. And it will become a talking point again when we see how few make it to university or employment.

Among the challenges are hunger, poverty, access to learning materials, language barriers and a challenge reported on previously in this column, inadequate support for educators.

Given the evidence, it may not come as a surprise to learn that the ability of education systems to ensure even rudimentary literacy skills for their students has declined in four out of 10 African countries over the past three decades.

These alarming findings are published in the first of a three-part series of Spotlight reports on foundational learning in Africa, called Born to Learn, published by the Global Education Monitoring (GEM) Report at UNESCO, the Association for the Development of Education in Africa (ADEA) and the African Union (AU).

African leaders gathered in Mauritius on Thursday, October 20, to discuss solutions to the education gap highlighted by a new United Nations education agency report, which shows children on the continent are five times less likely to learn the basics than those living elsewhere.

According to Manos Antoninis, director of the GEM Report, while every child is born to learn, they can’t do so if they’re hungry, lack textbooks, or don’t speak the language in which they’re being taught. Lack of essential support for teachers is another key factor. “Every country needs to learn too, ideally from its peers,” Antoninis said.

“We hope this Spotlight report will guide ministries to make a clear plan to improve learning, setting a vision for change, working closely with teachers and school leaders, and making more effective use of external resources.”

The report includes data from accompanying country reports developed in partnership with ministries of education in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Ghana, Mozambique, Rwanda and Senegal and a series of other case studies on the Continent.

“Africa has a complex past that has left parts of it with linguistic fragmentation, conflict, poverty and malnutrition that have weighed heavily on the education system’s ability to ensure universal primary completion and foundational learning,” the Executive Secretary of ADEA, Albert Nsengiyumva, said.

Nsengiyumva has said that the partnership shines a spotlight on this issue with education ministries to help find solutions that work. The social and economic consequences of low learning outcomes are devastating for Africa. “This report’s findings give us a chance to find a new way forward, learning from each other.”

The report finds that, in addition to socio-economic challenges, the limited availability of good quality textbooks, lack of proper teacher support, inadequate teacher training and provision of teacher guides were a bar to progress across sub-Saharan Africa.

But there are hopeful signs, too, as recent interventions show that progress is possible if efforts are focused on evidence-based classroom practices.

What good is this information if nothing were to come out of it to change the narrative?

Fortunately, the positive practices highlighted in the report and other experiences will be fed into a peer-learning mechanism on foundational learning. Hosted by the AU, the Leveraging Education Analysis for Results Network (LEARN), building on the Continental Education Strategy for Africa clusters, has been launched alongside the information.

If the politicians can take it forward beyond the idyllic Indian Ocean island talk shop, it would prove more than a refreshing break but a mindset shift for the Continent. Inevitably, the global impact of what the world has experienced since 2020 has left its mark on the planet.

Mohammed Belhocine, AU Commissioner for Education, Science, Technology and Innovation, said the Covid-19 pandemic thwarted efforts to ensure all children have fundamental skills in reading and maths.

“This is why a focus on basic education within our continental strategy’s policy dialogue platform is warranted. The work of the new LEARN network on basic education within the AU launched this week will draw from the experiences of countries that have taken part in the Spotlight report series.”

According to the report, there are several steps one must take to ensure that Africa shifts the dial when it comes to education. Thus, the key recommendations appear simple but depend on education budgets and the appetite to do more urgently.

The first step is a simple one: give all children textbooks to ensure that all children have learning materials that are research-based and locally developed.

Statistics they produced reveal that having their textbook can increase a child’s literacy scores by up to 20% with Senegal’s Lecture pour tous project, which ensured textbooks were high quality, cited as a winning example. Another was that of Benin, whose system-wide curriculum and textbook reform that has provided more explicit and direct instruction for teachers has received acclaim for its impact.

Given the multiplicity of languages, the report said the effect of teaching all children in their

home language could not be discounted. In 16 out of 22 countries, at most, one-third of students are taught in their home language. Mozambique’s recent expansion of bilingual education covers around a quarter of primary schools, with children learning under the new approach achieving outcomes 15 per cent higher than those teaching in one language. While this may be a winning suggestion, one wonders how it will accommodate the fact that English, French, Mandarin and Hindi are among the most spoken languages in the world.

But there are no one-size fits.

An area in which South Africa has seemingly done well is ensuring that children do not go hungry. The report recommends that all children be provided with a school meal. Only one in three primary school learners in Africa currently gets a school meal. Trendsetters in technology, Rwanda has committed to delivering school meals to all children from pre- primary to lower secondary education, covering 40 percent of the costs. It makes sense that children, humans with food in their bellies, can think and perform better.

The report calls for a commitment from governments to make a clear plan to improve learning by defining learning standards, setting targets and monitoring outcomes to inform the national vision. Easier said than done, which would depend on the finances and willingness to invest far more in education on the Continent.

Currently, it warns that there is no information on the learning levels of two-thirds of children across the region. This represents 140 million children. Far from being the pace-setters when it comes to research, it is the Ghana Accountability for Learning Outcomes Project is working on a framework for learning accountability.

In addition, the reports push for extensive teacher development, boosting capacity; in particular, a recent study covering 13 countries, 8 in sub-Saharan Africa, found that projects with teacher guides significantly increased reading fluency.

It calls for teachers to become leaders with the Let’s read programme in Kenya, which combines school support and monitoring with effective leadership and has seen improvements equivalent to one additional year of schooling for children.

Thanks to ubiquitous technology, something that could work far more effectively in the world now is sharing experiences between teachers and pupils across borders.

The Continent should not work in silos but ensure that education is relevant and makes a difference in a better continent. It can then ensure that its children are strengthened and enhanced through education.

Perhaps, the next time they have such a conference, they would borrow from the UN, which took youth leaders to New York, and hosts a competition for children to be part of the conversation. Why should politicians always have talk shops at fancy places like in Mauritius? Give the children a taste of the good life and a chance to aspire to do better than the concerning picture the report paints.

Naidu is a journalist and communications expert. He also heads up Higher Education Media Services – a social enterprise start-up committed to stimulating dialogue and raising awareness around education and the socio-economic, environmental, and political factors it influences in South Africa and the African Continent.

This article is original to the The African. To republish, see terms and conditions.