When TV crime mirrors daily life in Modi's India

Picture: Supplied - India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi can go abroad and promote India as the world's largest democracy all he likes, but the situation at home tells the real story, writes the author.

By Ruth Pollard

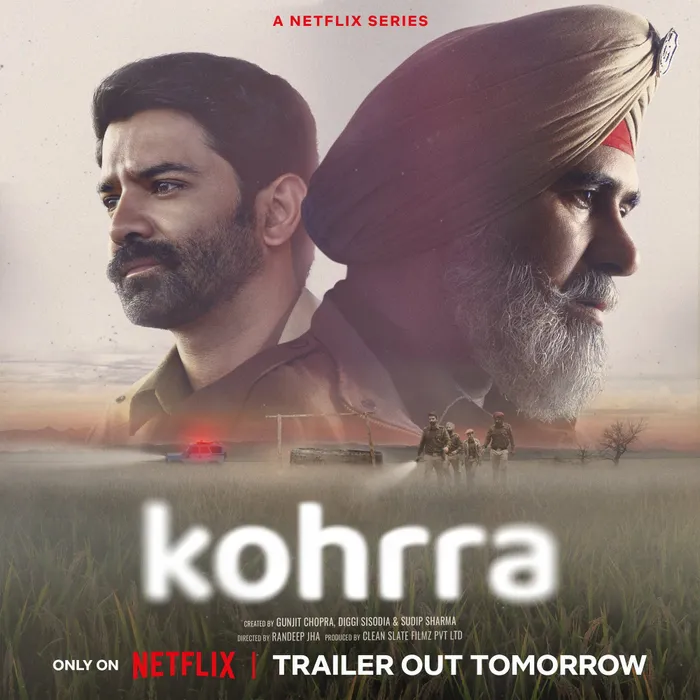

"Kohrra" is the latest Indian crime thriller to capture the attention of Netflix viewers, now in its third week at No. 1 of the streaming giant's Top 10 most-watched series in the South Asian nation.

If you haven't dipped your toe into this gritty genre - devoid of giant Bollywood dance numbers and cringingly improbable heroes - it's time you did. There, with other excellent dramas such as "Paatal Lok," "Delhi Crime" and "Indian Predator: The Butcher of Delhi," you will find the story of today's India writ large. Life imitating art: Corrupt politicians, violent cops, a society riven by caste and class divisions, and a staggering level of inequality.

While most reviews of "Kohrra" have focused on its complicated family dynamics, gang crime and the political pressure on law enforcement officers (or - spoiler alert - the gay subplot), for me what stood out was the casual, relentless police violence.

From regular beatings of suspects to an almost unwatchable assault on a man whose only crime was to date the chief inspector's daughter, it prompted me to ask around about whether the portrayals were overblown. "No, 100% accurate," came the responses from those who have closely observed the system.

Of course, there is more to India than crime and corruption - and it is not alone in battling these twin scourges. But it is hard to look away when news from the world's most populous nation reads, as it does, like a police procedural.

Last month, a horrifying video emerged showing two women being paraded naked and sexually assaulted in Manipur, prompting Prime Minister Narendra Modi to break his silence on the deadly months-long ethnic conflict in the northeastern state. Then a police officer shot dead three Muslim passengers and his superior on a train passing through the financial capital of Mumbai. Reports of men murdering and dismembering women are almost too numerous to count.

Just last week, communal tensions exploded into violence on the outskirts of the capital, New Delhi, where six people died in clashes between Hindus and Muslims in the neighboring state of Haryana. In the finance and technology hub of Gurugram - home to a raft of multinational companies like Alphabet's Google, Facebook-parent Meta Platforms and Hyundai - Haryana authorities insisted the situation was under control even as offices started sending staff home early and Muslim workers rushed to leave the city in fear for their lives. Instead of calming the situation, the government, led by Modi's hard line Bharatiya Janata Party, implemented a "demolition drive" in the district of Nuh, where much of the violence took place, bulldozing scores of mostly Muslim-occupied homes and shops it said were illegally constructed.

As Tanvi Madan, senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, wryly noted of the violence in Gurugram on X, formerly known as Twitter: "Say all you want that internal affairs are nobody else's business, but if you think various foreign businesses aren't calling their political risk divisions/consultants..."

In most cases, the main law enforcement tool - beyond the bulldozer and police brutality - is to shut down the internet. Manipur was in digital darkness for as many as 83 days (one reason the rape video took so long to surface) before a small easing of restrictions on July 25, while in Nuh, web and SMS services are currently closed until Aug. 8. For a fifth consecutive year, India led the world in internet shutdowns, according to 2022 data from the digital-rights group, Access Now.

Time and again, police have proved to be the Achilles' heel in India's security and stability, as Amit Ahuja and Devesh Kapur note in their excellent book Internal Security in India: Violence, Order and the State. In the most populous (and famously lawless) state of Uttar Pradesh - where the BJP is also in power - police are chronically understaffed despite sharp increases in crime, they write. Shortages at forensic labs were at 67%, while the traffic police faced a 70%-90% deficit. They also lack modern weapons "with about half of the police force using .303-bore rifles that had been declared obsolete by the Ministry of Home Affairs more than two decades ago," Ahuja and Kapur said.

Back in 2007, a government reform commission highlighted the serious obstacles police were facing: A poor civilian-to-police ratio, long delays in filling vacancies, an outdated legal framework, terrible working conditions where staff regularly logged 12-14 hours a day, weak infrastructure and a culture of influence from politicians and other powerful forces. As Ahuja and Kapur noted: "Mounting arrears of undetected crimes, delayed and denied justice and acts of violence that go unchecked all generate a sense of impunity among those engaging in such actions and frustration and anger in those at the receiving end. The widening gap between the two is an obvious threat to internal security."

Nothing has changed. And with India intensely focused on hosting the G-20 Leaders' Summit in New Delhi on Sept. 9-10, papering over these failings is clearly the priority.

Yet two terms of Modi's Hindu nationalist government have made their mark, and that has implications for security and the economy. Minority communities live in constant fear. Ethnic and sectarian violence is commonplace and the next big event on the horizon - the 2024 national elections - will only stoke those fires.

Modi can go abroad and promote India as the world's largest democracy all he likes, but the situation at home tells the real story. He shouldn't wait for the release of the next crime series to tell his supporters to dial it down. The time for that is now.

*Ruth Pollard is a Bloomberg Opinion editor. Previously she was South and Southeast Asia government team leader at Bloomberg News and Middle East correspondent for the Sydney Morning Herald.

This article was published in The Washington Post.