Pearl Harbour: site of Black heroism and protests against racism

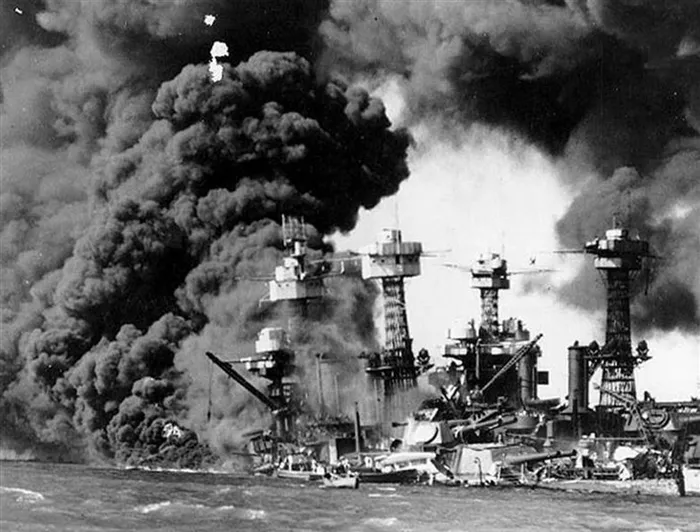

Picture: REUTERS/US Navy/Newscom – The USS West Virginia burns and sinks after the attack on Pearl Harbour, December 7, 1941.

By Matthew F Delmont

On January 4, 1942, more than 300 people filled the pews at the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, for a memorial service to honour Julius Ellsberry, a 20-year-old mess attendant first class killed during the attack on Pearl Harbour.

Ellsberry had volunteered for the Navy as soon as he turned 18, and on the morning of December 7, 1942, he helped several shipmates on the USS Oklahoma reach safety before he was killed. Birmingham World editor Emory O Jackson compared Ellsberry to Crispus Attucks, the Black hero who was the first American killed in the American Revolution. "No man not even an admiral can give more to his country than his life," Jackson wrote.

Ellsberry was one of dozens of Black men stationed at Pearl Harbor, which was a site of both Black heroism and organized protests against racism. More than 80 years later, these stories show how Black Americans are central to the history of World War II, revealing the absurdity of the US military's policy of segregation during the war – and offering lessons for eliminating institutionalized prejudices today.

At the start of the war, Navy policies dictated that Black volunteers and draftees could only be mess attendants, where they would serve and feed White officers. In the Navy's view, segregation was necessary for general ship efficiency. “This policy not only serves the best interests of the Navy and the country, but serves as well the best interests of Negroes themselves,” Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox said.

Black messmen serving in the Navy disagreed.

In 1940, 15 of them aboard the USS Philadelphia stationed at Pearl Harbour wrote to the Pittsburgh Courier asking for help publicizing their plight and discouraging other Black men from enlisting. Describing themselves as “sea going bellhops, chambermaids and dishwashers”, the messmen explained that White sailors were offered rank advancement after finishing training and given a pay increase to $36 per month, while Black sailors were paid only $21 a month and had limited opportunities for promotion. The men boldly signed their names to the protest letter, and the Navy quickly punished them with dishonourable discharges for two of the men and undesirable discharges for the rest.

In response, the National Committee for Participation of Negroes in the National Defence ran a large advertisement in the Courier urging readers to "REMEMBER THE THIRTEEN NEGRO MESSMEN OF THE USS PHILADELPHIA!," organise mass protest meetings and write to their congressmen. The military’s war plans excluded Blacks Americans, the ad warned. Even worse they, “DEGRADE you”. “They would make war without you if they could. They would challenge your right to citizenship ... Negros are Americans and you have a way to make known your wants.”

The NAACP’s Roy Wilkins also saw the Navy’s mess attendant policy as a fundamental challenge to Black citizenship and rights. “There is more to all this than standing on the deck of a warship in a white uniform,” Wilkins wrote in a powerful editorial in the group’s Crisis magazine.

“Being classified as a race, as mess attendants only”, came at a steep cost. The Navy offered White sailors valuable job training, education, healthcare, character building and travel. By contrast, Black Americans paid taxes to support the US Naval Academy and maintain naval bases, facilities and training programmes, from which they were excluded. Despite this clear bigotry and a denial of equal opportunity, White Americans expected their Black peers to “appreciate . . . the ‘vast difference’ between American Democracy and Hitlerism”.

The idea that mess attendants were in noncombat roles crumbled during the attack on Pearl Harbour. Enemy torpedoes made no distinction between White sailors and Black messmen. Doris Miller, a 22-year-old mess attendant aboard the USS West Virginia, used a fire hose to beat back the flames on the deck and pulled several sailors out of the burning water. Despite having no training on the ship’s weapons, Miller loaded ammunition and fired at the Japanese planes that continued to buzz overhead.

For Black Americans, Miller’s heroism at Pearl Harbour was a rebuke of the military’s policy of segregation. Miller showed that Black men could perform bravely in combat if only given the opportunity.

The sacrifices Black messmen made at Pearl Harbour were nowhere more evident than in the communities that mourned them. In Beaufort, SC, Navy veteran Adam W Bush mourned the loss of his son, Samuel Jackson Bush, who perished on the USS California. Similar scenes took place at memorials across the country. Moses Anderson Allen in New Bern, NC, Irwin Corinthia Anderson and Donald Monroe in Norfolk, and Andrew Tiny Whittemore in Nashville were each among the first Americans in their towns to die in World War II.

In Birmingham, Ellsberry’s parents and six younger siblings sat in the church’s front row. His mother thought of how Julius had written her just days before the attack to apologise for missing Christmas for the second year in a row. He enclosed a money order to buy presents for the family. The next letter she received was an official telegram from the Navy, saying that her son was lost in action in the line of duty and in service to his country. She was devastated to lose him. Nothing could bring Julius back, but she took pride in seeing his Navy picture displayed prominently in homes and businesses throughout Black Birmingham with the message, “Remember Pearl Harbour”.

Despite the heroism Black messmen demonstrated at Pearl Harbour, the Navy remained segregated through the end of the war.

This policy was costly and inefficient because it required the construction and maintenance of separate and redundant training facilities, as well as additional logistical planning for troop transportation and deployments. Military segregation made no sense for a nation trying to win a war; it made sense only for a nation trying to appease White racial prejudices. At the same time Army and Navy recruiters pleaded for volunteers after Pearl Harbour, they continued to turn away Black college graduates, doctors, language specialists, tradesmen and others with skills that would have aided the war effort. The Navy, Wilkins charged, “would rather not have a vital radio message get through than to have it sent by Black hands or over equipment set up by Black technicians”.

By 1944, Black Americans did begin to make inroads in the Navy. Black sailors were the majority of the crew on the USS Mason, a destroyer that protected ship convoys from German U-boat attacks as they crossed the Atlantic Ocean. The men aboard the Mason had the rank and responsibilities of combat sailors, which had previously been denied to Black mess attendants. That same year, the Navy commissioned its first 13 Black officers, who joined more than 100,000 Black enlisted sailors. In 1945, Phyllis Mae Dailey became the first African American sworn in as a Navy nurse, and she was one of only four Black women to serve in the Navy during World War II.

In February 1946, without great fanfare, the Navy issued Circular Order 48-46, which ended the Navy’s official policy of segregation and assignments based on race. In 1948, President Harry S Truman signed Executive Order 9981 mandating desegregation of all branches of the US military. While many White military officers and enlisted men dug in their heels and resisted the order, by the end of the Korean War in 1953, the military was almost fully desegregated.

There are now decades of evidence that racial integration has been good for military readiness and effectiveness. More broadly, the steps toward equality that the Navy and other military branches made in the years after World War II offer an important example that significant institutional change is possible.

When the war ended in 1945, it was unimaginable to many Americans that the military would ever be integrated. Millions of Americans supported the status quo of segregation and worked to actively uphold racial hierarchies during the war. If Truman had waited for public opinion polls to show majority support for racial integration, he would have been waiting a long time.

Today, when many of our nation's challenges can seem intractable, the desegregation of the military offers an example of a bold step toward racial equity.

Matthew F Delmont is the Sherman Fairchild Distinguished professor of history at Dartmouth College and author of the new book “Half American: The Epic Story of African Americans Fighting World War II at Home and Abroad”.

This article was first published in the Washington Post.