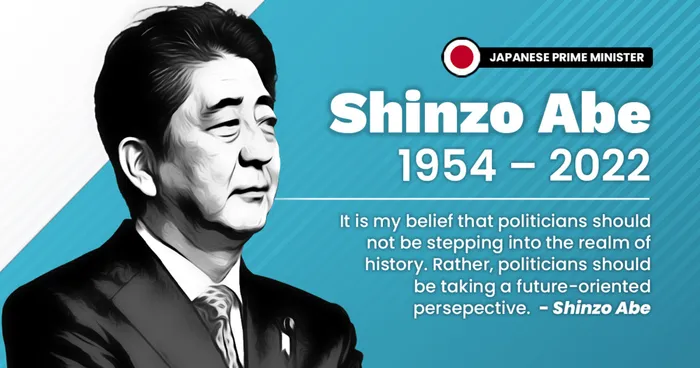

Four Ways to See Shinzo Abe’s Legacy

Graphic: Timothy Alexander/African News Agency (ANA)

By Ishaan Tharoor

The family of Shinzo Abe held a wake Monday, a day before his funeral today. Japan and, indeed, much of the world, remains stunned by the assassination of the former prime minister, which took place at an election rally Friday where Abe was stumping for a local candidate. In the 21st century, such fatal shootings of prominent leaders are exceedingly rare, let alone in a country that registered only one gun-related homicide in 2021.

Police have opened an investigation, and the culprit, who has confessed guilt, said the killing was not politically motivated.

Abe leaves behind a considerable and complex legacy. He is the longest-serving Japanese premier in post-World War II era and a leading proponent of Japan's economic reform and geopolitical reimagining in the 21st century. His loss was memorialised around the world – flags flew at half-staff from Washington to New Delhi to myriad other capitals.

Here are some ways in which he will be remembered:

– The pre-eminent statesman of the Indo-Pacific

In power for much of the past decade, Abe pushed forward what he and his allies dubbed a “proactive“ vision of Japan’s place in Asia and the world. Abe tugged at the 20th-century tethers that restrained Japan under a pacifist constitution and sought to focus attention on the threats posed by a saber-rattling, nuclear-armed North Korea and an expansionist China.

“Abe’s approach to China – a healthy mix of hawkish skepticism and realpolitik acknowledgement of its trading status – became what is now the backbone of western policy of President Xi Jinping's regime,“ wrote Bloomberg's Gearoid Reidy.

His energetic global diplomacy – visiting more than 80 nations in his tenure – yielded mixed results. Few world leaders called on Russian President Vladimir Putin as frequently as Abe, but those overtures did little to mend fences between the Kremlin and the influential Group of Seven nations. In 2019, an Abe mission to Iran awkwardly preceded a deadly conflagration over the Persian Gulf.

But Abe did emerge as the linchpin in a new vision of Asian security, one that was loosely strung around cooperation with major regional democracies, with the United States (US) also closely involved. More than previous Japanese leaders, Abe was deeply animated by the perceived need to hedge against China’s rise.

“He knew two things: that the US’s continued presence is vital for the region and beyond, and that for the US to stay engaged in the region, Japan is vital,“ Tomohiko Taniguchi, a longtime Abe foreign policy adviser and speechwriter, told The Washington Post’s Josh Rogin. ”His tactful relationship-building [efforts] both with [Barack] Obama and [Donald] Trump were all based on that realist consideration.”

“Abe was the first world leader to elaborate the vision of a free and open Indo-Pacific,” wrote HR McMaster, former national security adviser in the Trump White House. “He encouraged co-operation among the so-called Quad – Japan, the US, Australia and India – to address emerging challenges in the region.”

“I think he will be remembered as among the most consequential leaders of contemporary Asia,” the White House’s top Asia-focused official, Kurt Campbell, said to reporters after Abe’s death.

– The assertive – and divisive – nationalist

At home and in Japan’s neighbourhood, Abe was hardly a figure of consensus and unity. His right-wing nationalism periodically incensed the public and officials in nearby China and South Korea, where Abe’s denial or downplaying of Japanese atrocities during World War II rankled. His unrealised desire to amend the country’s pacifist constitution to change the footing of Japan’s “self-defence” forces was bitterly opposed by adversaries to the left and remains a source of tension within Japanese politics.

“He was the most polarising Japanese political figure in several generations, a political battler whose commitment to his vision of the country’s future invited the adoration of his friends and the opprobrium of his critics,” wrote Tobias Harris, a senior fellow at the Centre for American Progress.

“While many are extolling him as a great leader, his personal vision for rewriting Japanese history, of a glorious past, created a real problem in East Asia which will linger, because it divided not just the different countries’ approach to diplomacy with Japan; it also divided Japanese society even further over how to approach its own responsibility for wartime actions carried out in the name of the emperor,” Alexis Dudden, historian of modern Japan and Korea, told the New Yorker.

– The champion of the neo-liberal order

His bid to revive Japan’s stagnating economy after the global financial crisis – a set of pro-growth policies dubbed “Abenomics” – achieved mixed results. Company profits surged and unemployment was halved while he was in office, but he still fell short of his stated goals.

“Abe was thwarted; the core ambition – a 2 percent inflation target – was never met on his watch,” explained a Financial Times editorial. “But the effort was not in vain. Ultra-expansive monetary policy successfully weakened the yen and cut borrowing costs. His ambitions were let down by fiscal squeamishness – in particular, by raising the consumption tax too quickly, which choked off momentum. Japan needed more of Abe’s bold positivity, but benefited from what it got.”

On the world stage, at a time of ascendant populism in the West, Abe emerged as a pillar of the traditional “liberal” order. He was a proponent of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) – an ambitious US-led free trade pact – and worked to keep it, or a version of it, alive after it was nixed by President Donald Trump.

– The “shadow shogun”

Even out of office, Abe loomed large over Japanese politics and was a commanding figure of an influential faction within the ruling Liberal Democratic Party. His authority and kingmaker role led him to be hailed by some as the “shadow shogun” within the party.

Now, Japan’s politicians are left to navigate an economic and political environment conditioned for years by Abe’s agenda. After the ruling party secured a clear majority in Japan’s upper house of the parliament, Prime Minister Fumio Kishida, an Abe ally, finds himself in a “golden period” of three years without elections to complicate his rule. He had set about on a somewhat different course than his predecessor, invoking a “New Capitalism” that sought to tackle economic inequality and was, in some senses, a tacit rebuke of Abe’s neo-liberalism.

Abe’s death “may now make it more difficult for Kishida to distance himself from Abe so explicitly”, explained Bloomberg’s Reidy. “In the coming months, he will have to decide on a replacement for Haruhiko Kuroda at the Bank of Japan, a decision that may define Kishida’s entire economic legacy. Abe’s death comes as the yen drops to a historic low; and there is intense pressure on the BOJ to join other central banks in tightening, though Kishida has been broadly supportive of the Abe-Kuroda consensus so far.”

Tharoor is a columnist on the foreign desk of The Washington Post

This is an edited version of an article originally published in the Washington Post