Challenging SA’s moral standing on African affairs

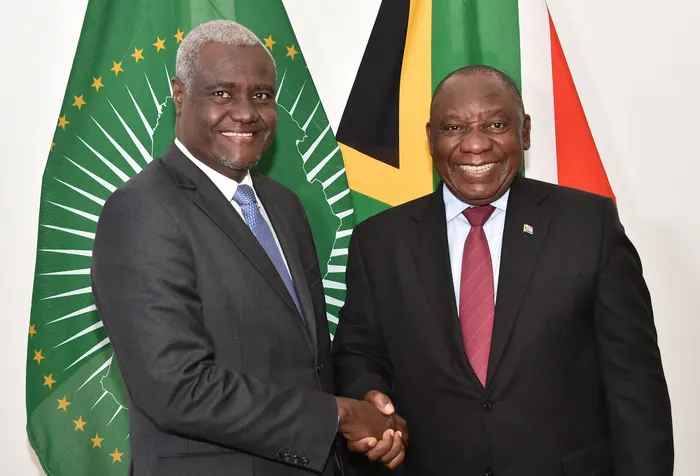

File picture: Kopano Tlape/GCIS - President Cyril Ramaphosa with African Union Commission chairperson Moussa Faki Mahamat at luncheon meeting at his Mahlamba Ndlopfu residence in Pretoria, South Africa.

By Dr Omololu Fagbadebo

South Africa is a paradox. As a rainbow nation with racial diversity, it is also a society characterised by internal socio-political divisions and inequality.

In the international system, South Africa is a key player in Africa’s politics and economy. A little Europe in Africa, Pretoria is a symbol of African pride, capable of competing with other actors in the international system.

With a gross domestic product of $418 billion (R7.8 trillion), South Africa ranks as the second-largest economy on the continent but, undoubtedly, the most industrialised with a robust manufacturing sector.

South Africa also has an enviable higher education system that attracts foreign African nationals. Hence, it is the destination for African migrants for greener pastures and quality education.

In terms of its pivotal role in continental affairs and politics, South Africa is an influential member of the AU. Since the end of apartheid in 1994, Pretoria has emerged as a power broker and an active member of the continental body. The country played a crucial role in the transformation of the Organisation of African Union into the AU, with former president Thabo Mbeki as its first chairperson in 2002. His tenure bolstered the institutionalisation of the continental socio-economic development flagship, the New Partnership for Africa’s Development (Nepad) and its governance mechanism, the African Peer Review. Dr Nkosazana Dlamini Zuma was the third chairperson of the AU Commission, from 2012 to 2017.

Post-apartheid South Africa rejigged its pariah status in the international system “to exercising leadership regionally and globally” and became a “norm- and agenda-setter” for the continent.

South Africa enjoyed its diplomatic honeymoon on the continent as Nelson Mandela became a colossus, well respected and adorned by world powers. The fame increased the status of Pretoria in global affairs as the country became the African giant in diplomatic shuttles, with a buoyant domestic environment. Mandela’s South Africa was the doyen of African international relations, with foreign powers extending diplomatic gestures and partnerships. Mandela led South Africa’s advocacy for a restructured global system and institutions, notably the UN Security Council.

Given its apartheid experience, Pretoria was at the forefront of championing a new world order based on respect for rules, human rights, peace, especially in Africa and multilateralism. South Africa is also a member, (the only African country) of the G20, a forum for international economic co-operation. Its intercontinental tentacles include IBSA and BRICS. As the southern African hegemon, Pretoria is the only African member of the BRICS, an intercontinental regional organisation.

As a leading member of the AU, Pretoria is expected to showcase the Nepad objectives of poverty eradication, promotion of sustainable growth and development, integration of the African economy into the global economy and acceleration of women’s security and empowerment.

Yet, it has the highest crime rate on the continent and the third highest in the world, a development that has made it the most dangerous country in Africa and one of its cities the “murder capital of the world”. An unemployment rate of 32.9%, with 61.60% of the population in poverty and less than 20% of citizens holding and controlling more than 70% of national resources and income are notable drivers of insecurity and violence. Socio-economic inequality has engendered structural violence that drives other forms of violence and criminal activities in the country.

The worsening governance crisis has stretched the country’s public service delivery capacity. Rather than take responsibility for the country’s structural failure, attributing the challenge to African nationals aggravated xenophobic violence that has pitted Pretoria against its fellow African nations. This does not support its supposed continental status as an economic giant.

With changes in its foreign policy objectives in terms of emphasis and application, Pretoria is seeking to advance its relevance beyond continental politics. President Cyril Ramaphosa is the leading light of the ‘African Peace Mission’ in the Russia-Ukraine war. This is perceived as Pretoria’s initiative because such a diplomatic adventure ought to have been undertaken by the AU Commission. But its support for Russia in the war put a moral dent in the integrity of the “mission”. Thus, the mission cannot be an African agenda, given the plethora of unresolved conflicts on the continent, notably, Sudan, South Sudan, Ethiopia, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Cameroon. The US had doubted Pretoria’s neutrality in the war, given the Lady R saga and Russian President Vladimir Putin’s impending attendance at the BRICS Summit in August.

There is a need to address the burgeoning crisis of governance, recently compounded by the challenge of electricity supply, a major issue that has reduced its manufacturing capacity. An inclusive governance structure devoid of grafts and state capture phenomena is a necessity to restore the waning influence and glory. It is time for Pretoria to reshape its foreign policies and demonstrate its multilateral stance on the continent, through a more accommodating diplomatic rule with comparative advantages.

*Dr Omololu Fagbadebo is from the Department of Public Management, Law and Economics at the Durban University of Technology.