Mbeki, Zuma Resistance Undermining the Struggle for Truth and Justice

TRC'S UNFINISHED BUSINESS

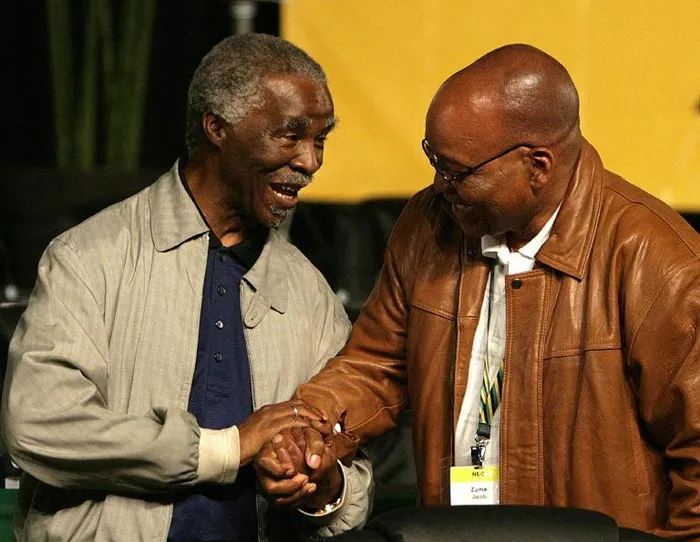

Newly elected leader of the ANC Jacob Zuma (right) is congratulated by outgoing ANC President Thabo Mbeki (left) on 18 December 2007 in Polokwane. The Khampepe Commission represents another defining test of South Africa’s democratic maturity. The resistance by Mbeki and Zuma reveals the enduring power of elite consensus and controlled memory, says the writer.

Image: AFP

Dr Clyde N.S. Ramalaine

South Africa finds itself at a defining historical juncture. The contestation surrounding the Khampepe Commission is not merely about law, procedure, or political rivalry. It concerns the moral architecture of the democratic state and whether a nation born out of compromise, through a negotiated settlement now sustained in a grand coalition, dares to interrogate the very foundations of that compromise.

The resistance by former presidents Thabo Mbeki and Jacob Zuma must therefore be understood beyond the narrow legal language in which it is framed. At stake is the legitimacy of South Africa’s transition, the integrity of its liberation legacy, and the dignity of those whose suffering was deferred in the name of reconciliation without recompense and peace without truth.

The central question that reverberates through public discourse remains simple yet unsettling: what, precisely, are these former presidents seeking to protect?

Any serious engagement with the Commission must begin with its ontology, its moral logic, and constitutional necessity. The inquiry exists because South Africa’s transition left unresolved contradictions. It is not a partisan project but an epistemic and constitutional intervention aimed at restoring coherence between the ideals of justice and the realities of political settlement.

Its mandate is to investigate the failure of the democratic state to prosecute apartheid-era crimes, particularly those identified during the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Many perpetrators implicated in gross human rights violations neither sought nor received amnesty, yet were never prosecuted. This produced a profound ethical and constitutional deficit. The promise of accountability gave way to inertia.

The intended outcomes are threefold: the recovery of truth through an authoritative historical record; accountability, whether criminal, institutional, or symbolic; and restorative justice that affirms the dignity of victims whose suffering was subordinated to the pursuit of political stability. In this sense, the Commission marks a transition into a post-reconciliation phase, in which justice must move beyond symbolism.

The emergence of the Commission in 2025 reflects accumulated frustration. Victims and civil society refused silence. Litigation, advocacy, and sustained public pressure compelled the state to act. This development is less the product of executive generosity than constitutional insistence.

President Cyril Ramaphosa initiated the inquiry amid declining institutional credibility. Corruption, governance failures, and prosecutorial paralysis had eroded public trust. The Commission thus functions as both a constitutional reckoning and a legitimacy project, personal and institutional.

It seeks to restore confidence in the rule of law without destabilising the negotiated settlement. Yet this balancing act remains precarious. Truth, once unleashed, rarely remains contained.

The legal and moral case advanced by victims is both restrained and compelling. Their primary grievance is institutional betrayal. They argue that the democratic state extended de facto impunity to perpetrators through inaction.

Submissions emphasise violations of dignity, equality, and access to justice. They point to prosecutorial failure, political interference, and the emotional and material consequences of decades of silence.

A central concern arises from testimony by former National Director of Public Prosecutions Vusi Pikoli, who asserted that he was instructed by Mbeki not to proceed with certain prosecutions. If sustained, this challenges the notion of prosecutorial independence within South Africa’s constitutional order.

Yet this claim introduces a troubling contradiction. Pikoli also resisted executive pressure in the case of Jackie Selebi, demonstrating institutional courage. The question that emerges is why a similar resolve was not displayed when apartheid-era prosecutions were allegedly halted. This inconsistency demands scrutiny.

The tension complicates claims of institutional rectitude. It raises deeper concerns about political calculation, institutional culture, and the uneven application of constitutional principle. It suggests that the failure of accountability resulted not only from political interference but also internal ambivalence.

South Africa’s prosecutorial independence has often been asserted in principle, yet it has been uneven in practice. The contrast between the Selebi case and apartheid-era prosecutions underscores the central concern: whether justice was selectively pursued and victims subordinated to political expediency.

For victims, the struggle is not about seeking vengeance, but about gaining recognition. Reconciliation without accountability entrenched a hierarchy in which perpetrators were protected, and victims marginalised. This asymmetry remains one of the transition’s most enduring moral failures.

The Commission reopens debate on the negotiated settlement shaped through the Convention for a Democratic South Africa. The so-called miracle avoided civil war but prioritised stability over justice. Amnesty in exchange for disclosure was central, yet consistent prosecution where amnesty was neither sought nor granted never materialised.

The Anglican Cleric Desmond Tutu-led TRC reinforced a reconciliation imperative that, while morally compelling, enabled what may be termed a managed silence. Political elites prioritised continuity and legitimacy. Victims of exile camp abuses and apartheid atrocities became inconvenient truths in a nation-building narrative.

The Commission disrupts this equilibrium. It insists that historical justice cannot be selective.

Ramaphosa represents technocratic constitutionalism, seeking institutional renewal without destabilising the political order. Mbeki reflects an intellectual elite concerned with historical narrative and preservation of the liberation movement’s moral authority. Zuma represents populist mobilisation and scepticism toward legal processes, framing the inquiry as selective.

Despite these differences, both Mbeki and Zuma share proximity to the transition. They were central brokers in negotiations that shaped democratic South Africa. Their resistance suggests anxiety about broader implications beyond personal reputations.

Their actions reveal a layered strategy:

• Legal challenges questioning the mandate and constitutionality.

• Procedural delays are slowing testimony and frustrating victims.

• Narrative framing mobilising different constituencies.

• Institutional scepticism undermining public confidence.

This convergence, despite rivalry, signals systemic stakes.

The Commission threatens to expose political decisions, informal understandings, and strategic compromises prioritising stability over justice. The issue may not be personal guilt but institutional complicity. If impunity were structurally embedded, the foundational myth of the transition would be destabilised.

A striking contradiction emerges. Leaders of the liberation struggle now appear to defend those implicated in apartheid-era crimes. This reflects a broader paradox of postcolonial governance, where movements in power prioritise stability over transformative justice. What was rationalised as peace now appears as deferred injustice. Victims increasingly view the democratic state as complicit.

Legal disputes may therefore function as a smokescreen masking deeper struggles over historical memory and legitimacy. Should the Commission succeed, it may expose structural compromises that shaped contemporary inequality and institutional weakness. The stakes extend beyond past crimes to present governance.

The Khampepe Commission represents another defining test of South Africa’s democratic maturity. It asks whether reconciliation was an endpoint or a beginning. The resistance by Mbeki and Zuma reveals the enduring power of elite consensus and controlled memory. Yet history resists suppression.

The victims of injustice are not adversaries of the liberation legacy but its unfinished conscience. If allowed to proceed, the Commission may redeem rather than destroy that legacy. The true miracle of South Africa will not be the avoidance of conflict but the courage to confront truth.

Ultimately, South Africa’s future depends on whether it chooses silence or accountability.

* Dr Clyde N.S. Ramalaine is a political scientist and analyst whose work interrogates governance, political economy, international affairs, and the intersections of theology, social justice, and state power.

** The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of IOL, Independent Media or The African.