Matric 2025: Celebrating Success or Perpetuating Inequality?

BASIC EDUCATION

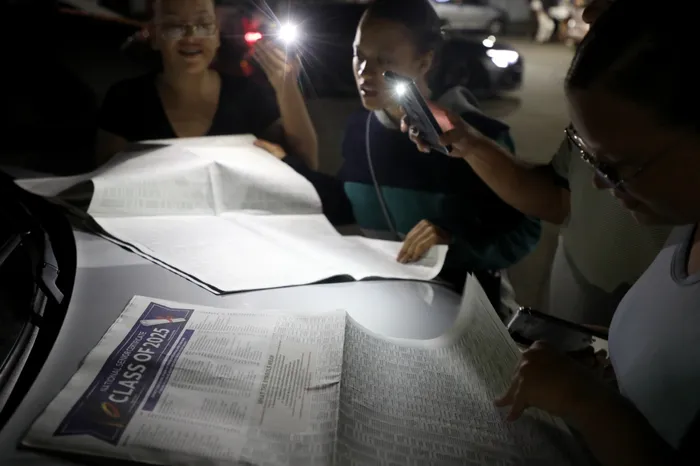

Gauteng matriculants gathered in their numbers at Independent Media's printers to obtains their matric results on January 13. The sooner basic Education Minister Siviwe Gwarube teams up with Higher Education and Training Minister Buti Manamela and works out a cohesive pipeline from schooling to post-school opportunities, the better it will be for South Africa, says the writer.

Image: TIMOTHY BERNARD

Edwin Naidu

As the euphoria around the matric 2025 results cools down, the focus turns to university admissions. But the burning question over the public versus private education debate remains. One has to ask whether the elite Independent Examinations Board (IEB) schooling system is better equipped to give one’s child a better head start in life than the current National Senior Certificate (NSC) public system?

Despite massive transformative shifts aimed at redress and inclusion, the annual noise around the matric gives one the impression that the system continues to perpetuate the apartheid goals. On the stage at the MTN auditorium, the Government of National Unity Minister of Basic Education, Siviwe Gwarube, celebrates the top achievers. Ditto these celebrations throughout the country as the Education MECs celebrated the cream of the crop in provincial public schools. The same scenario played out at private schools as IEB announced the results.

Beaming parents, varsities scrambling for the best, learners brimming with enthusiasm over their bright futures. Why celebrate the cream of the crop when most learners who have sat the 2025 matric exams in public schools are still mired in poverty and have finished their schooling unemployed with little prospects?

Gwarube did not mention those who failed the education system on Monday, when the results were announced. At the IEB celebrations, they talk only about those with distinctions too, which includes the majority of their learners.

When former President Thabo Mbeki spoke of two nations in one country, he meant a relatively prosperous, developed, white-dominated "first nation," and a larger, poorer, underdeveloped black "second nation," divided by vast economic and infrastructural inequality, a stark legacy of apartheid that persists despite democracy.

Three decades after democracy, one does not expect these challenges to shift. However, annually celebrating the haves shows just how captured the government is by privilege. Of course, many in the public system come from poor backgrounds whose parents worked hard to get them through school. I am not denying their selfie moment with Gwarube.

But one must ask: What good is a schooling system out of which only one-third get a university pass? Of course, there is no guarantee of acceptance, as tertiary institutions can accommodate over 200,000 students.

Is it unfair to claim that the majority remain suppressed with a gloomy future? Despite billions of rands being pumped into education, there is currently no evidence that the government has yet shown returns. All we see is good public relations.

Ironically, and sadly, before the announcement of the matric results, to put things into perspective of the shallow progress over the past three decades of democracy, a six-year-old girl drowned after falling into a pit toilet in Nkuzana Village, Limpopo. This little girl will never matriculate and have the opportunities that continue to elude many.

The number of deaths in pit latrines continues despite the constitution compelling the government to protect children and eliminate pit latrine toilets in the country. If, under a GNU, children cannot be protected as a constitutional obligation, do we really expect them to be prepared for a bright future?

Given the growth of private higher education institutions in South Africa, statistics show that many IEB students are opting for private education providers rather than public universities. This is an indictment of the system, plagued by a variety of issues, which, though there are pockets of excellence, is struggling. Add to the mix that thousands of graduates are unemployed, with their degrees doing little to enable them to contribute to the economy or their families.

While the comparison may not be entirely fair, the evidence is clear that the IEB 2025 Matric results, which revealed a 98.31% overall pass rate out of 17,413 candidates allows the haves to enjoy an easier bite of the tertiary opportunities

Consider the exceptional IEB pass rate which remains among the highest globally for school-leaving qualifications, strong university readiness in which nearly nine in ten students qualify for degree-level study and a balanced qualification mix of Diploma and Higher Cert entries reflect diversified post-school pathways. Furthermore, it highlights student excellence, with 286 learners achieving distinction-level recognition across multiple subjects.

Now look at the NSC, which achieved a record high 88%, the highest ever for more than 900,000 candidates, but good only for a third. In 2025, over 656,000 learners passed the National Senior Certificate. So, what happens to the 244,000 learners who did not make the grade? The results show low math participation, declining gateway subject performance, and an increasing number of learners who dropped out in grades 11 and 12.

Credit to Gwarube for taking over the baton from long-serving Angie Motshekga, but I don’t take comfort in the fact that she is proud of the fact that “We are reaching more learners in Grade 12 than at any other point in decades”. Numbers mean little when the result of tens of thousands is failure.

Alarmingly, only 34% of candidates wrote Mathematics. In contrast, most wrote Mathematical Literacy, meaning that the majority of candidates from the Class of 2025 will not be ready for the world of Artificial Intelligence. They cannot study further in AI, science, or technology subjects, as these require good results in maths.

So does that mean a vast majority of those who make it to university will study humanities, and that joblessness?

Really, we have nothing to celebrate. The sooner Gwarube teams up with Higher Education and Training Minister Buti Manamela and works out a cohesive pipeline from schooling to post-school opportunities, the better it will be for South Africa.

Manamela has thrown his weight behind artisanal skills through TVET colleges, and he is right: not all school leavers can be scientists, doctors, or lawyers. We need welders, plumbers, and electricians. TVET colleges have received massive government investment, and some are leading the way in robotics and technology. The Sector Education Training Authorities can also be cajoled into doing better; some are, but they get a bad reputation from a few rotten apples.

The task to fix education is not a magic wand. But a desire to want South Africa to become a great nation. One wonders why there is not a greater connection between private and public education. It is not just about having the best infrastructure and resources, but also about teachers who are committed to producing the best.

Teachers are integral to positive education outcomes. But as a nation, we cannot annually celebrate mediocrity and then keep the cycle going. It’s the reason we continue to have two educational South Africas – innovative and privileged, with vast potential, and failed and doomed without opportunities - by a system that remains premised on celebrating a few.

* Edwin Naidu is a strategic communications expert in financial services, driving mentoring and dialogue initiatives in higher education through Higher Education Media Services.

** The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the opinions of IOL, Independent Media, or The African.