A Fearless News Hound: Subry Govender's Courageous Struggle To Tell The Truth

BOOK EXTRACT

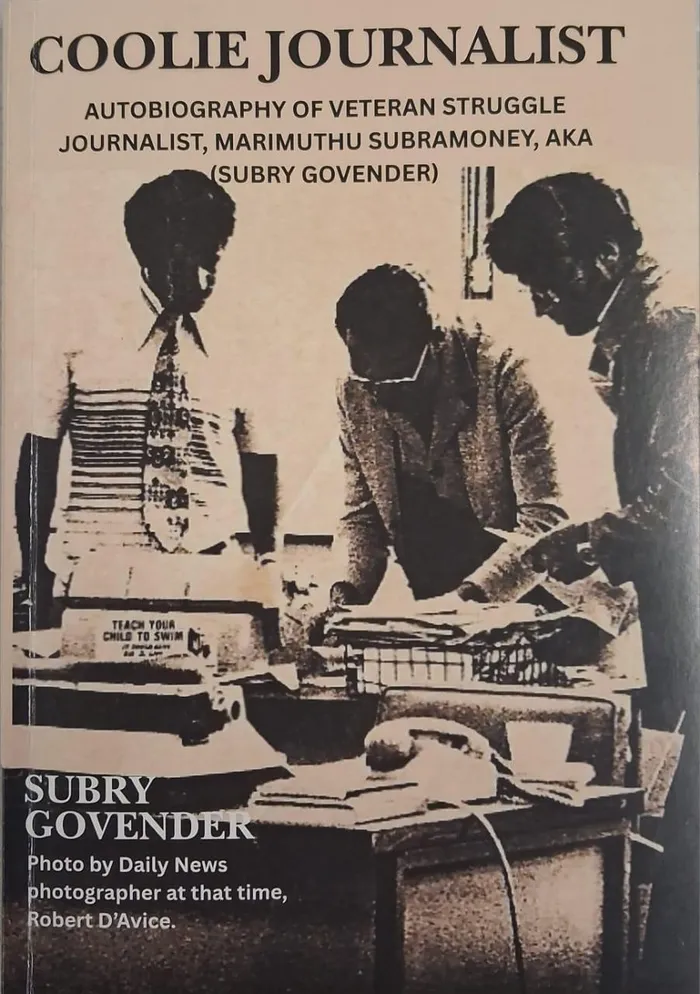

The book cover of veteran journalist Subry Govender's autobiography titled 'Coolie Journalist'.

Image: Supplied

In his autobiography titled 'Coolie Journalist' veteran Durban based struggle journalist Subry Govender reflects on his journey as a journalist despite unrelenting harassment by the apartheid-era security police, bannings and imprisonment. The 'Coolie Journalist' will be launched on January 25 at the Umhlanga Apart Hotel, Durban. The following is an extract from the book:

'You are nothing more than a Coolie journalist.'

It was around 3 a.m. on a weekday in the fourth week of May 1980. I heard frantic knocks on our door. It was my mother. Speaking in our Tamil mother tongue, she said: "Sadha, rende vela karagango inga irakarango. Una pakanoma."

(Translated: “Sadha (that's my cultural name), two white men are here. They say they want to see you.")

My wife, Thyna, and our son, Kennedy Pregarsen, and daughter, Seshini, and I used to occupy the outbuilding at number 30 Mimosa Road, Lotusville, Verulam - just north of Durban. My mother, Salatchie, my father, Subramoney Munien, and my brothers - Dhavanathan (Nanda), Gonaseelan (Sydney), and Gangadharan (Nelson) and sisters - Kistamma (Violet) and Natchathramah (Childie) - used to occupy the main building. My eldest sister, Mariamah (Ambie), was married at this time, and she was staying in the area of Phoenix - about 15km south of where we were residing.

Clearly in a sleepy mood, I opened the door to find two white security policemen with awkward smiles on their faces. I recognised one of them as Sergeant De Beer. He was one of the security policemen who questioned my position when I worked at the Daily News from the early 1970s to the late 1980s. I saw him questioning one of my Daily News colleagues outside the Daily News building at the former Field Street in the city of Durban. My colleague informed me later that De Beer had questioned him about my work at the Daily News.

On this occasion at my home in Lotusville, Verulam, he looked at me and, with a quirky smile, said: "Mr Subramoney, we have come to search your house and for you to accompany us back to the office."

At the same time, members of the security police were conducting similar raids at the homes of my colleagues and officials of the Media Workers Association of South Africa (MWASA) in the cities and towns of Johannesburg, Pretoria, Cape Town, Port Elizabeth, East London, Bloemfontein, and other parts of the country. In addition to us as journalists, the security police also raided the homes of political activists, such as Vijay Ramluckan, who became one of Nelson Mandela’s doctors after his release in 1990, and Yunus Shaik, brother of Moe Shaik, who became an ambassador in the new South Africa.

I informed De Beer that my family members were asleep and their visit was inappropriate. Their unannounced visit at such an unearthly early hour was an intrusion and would be disturbing my family. De Beer did not seem to care, and he and his colleague just pushed their way in.

"Where are all the communist books you keep?" De Beer and his colleague asked in gruff voices.

"I don't know about communist books, but here are all my files and literature," I responded.

I did have some communist literature, but this was stored away in the ceiling of the house. I used to receive material from the banned Communist Party of South Africa despite not being a member. I used to read the booklets and then store them in the ceiling.

"We want you around when we search your files and books," they said.

So, I watched them go through my files with a “fine-tooth comb" and read every letter in one of the files.

Suddenly they burst out laughing, and one of them said, "Here's an interesting letter."

It was a letter I had written sometime in the late 1960s to the then Prime Minister of India, Mrs Indira Gandhi.

I was still a "greenhorn" at that time. I was just learning about the political situation, the world, and the land of my ancestors - India. I did not know what went through my head that on one fine day, I sat at my typewriter and penned a letter to Mrs Gandhi. I told her about the oppression of people of colour in South Africa and asked her whether India was doing anything about it.

Mrs Gandhi knew something about South Africa. As a teenager, she stayed a few days in Durban while en route from London to India. She was the guest of members and officials of the progressive and influential Natal Indian Congress, a powerful ally of the African National Congress (ANC) during the dark days of the struggle against white minority rule and domination in the 1940s, 1950s, 1960s, 1970s, 1980s, and early 1990s. I was informed that two of the people she had met were struggle stalwarts, Mr Ismail Meer, who was a member and official of the Natal Indian Congress, and his wife, Professor Fatima Meer, who was a sociologist, author, and social activist at that time.

The letter to Mrs Gandhi read:

"Dear Mrs Gandhi. I am a South African whose forefathers and mothers had come down from India to the country since the 1860s to work as indentured labourers on the sugar cane plantations of the former Natal Colony.

"Our people have made great strides despite decades of slavery, colonial rule, and apartheid oppression.

"Leaders of our community, such as Dr Yusuf Dadoo, Dr Monty Naicker, Dr Kesaval Goonum, George Singh, J N Singh, Ismail Meer, Fatima Meer, Billy Nair, Mac Maharaj, Sonny Singh, and thousands of others, have made enormous contributions and sacrifices in the struggles against White minority rule and oppression.

“The situation is now deteriorating, and I would like to know whether the Government of India will be doing anything to promote our liberation."

I did not post that letter. But I did not tell the security policemen that. I wanted them to believe that I had really sent that letter to Mrs Gandhi.

After about an hour of searching through my files, the two security policemen put everything they wanted together in a pile and then told my wife:

"You are not going to see your husband for some time. He would need some clothes."

They did not clean up the mess they caused through their invasion and search. My wife, Thyna, had to clean up after I was taken away.

While they were conducting their search, my son, Kennedy Pregarsen, who was six years old, and my daughter, Seshini, who was three years old, woke up, and they were wondering what these strange white men were doing in our home.

It was around 6 am when De Beer and his colleague said they were finished, and I should join them.

As I was walking with the security policemen, I could see my son, Kennedy Pregarsen, watching with concern in his eyes, and my wife was really worried. When my son was born, I was looking for a name, in addition to a Tamil cultural name, for him. I recalled the assassination of John F. Kennedy two decades earlier when our family stayed in the neighbouring rural village of Ottawa. I was studying for my matriculation examinations at this time when I heard over the radio that President John Fitzgerald Kennedy was assassinated. I considered Kennedy to be a great liberal who introduced reform measures to uplift the lives of the discriminated African-American people.

That is how my son got the name Kennedy. From an early age, he became aware of our struggles, punching his right fist into the air and shouting "Amandla Awethu" (Power to the People) became a norm for him.

I told my wife not to worry and to telephone my news editor, Mr David James, at the Daily News.

My mother and my younger brothers and sisters were also watching closely.

In the car, the two security policemen told me that I was involved with communists and that I was in big trouble. De Beer said, "Mr Subramoney, you have a young family, why are you involving yourself with communists? You are associating yourself with terrorists. You are nothing more than a Coolie journalist, and we will make your life very difficult."

I just kept silent. I was too shocked.

This was not the first time that I had come into contact with the security police at close range.

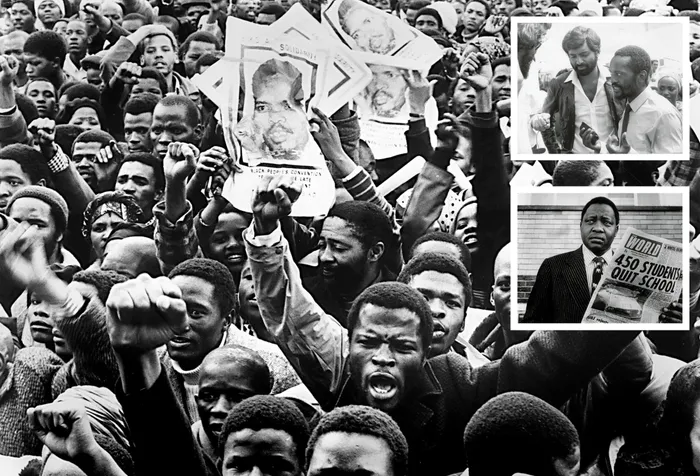

MOURNERS at the funeral of Black Consciousness (BC) leader Steve Biko in King William’s Town on September 25, 1977. INSET TOP: Then South African Students’ Organisation leaders Saths Cooper, Aubrey Mokoape and Strini Moodley were imprisoned for their BC activism. INSET BELOW: Percy Qoboza, editor of The World and Weekend World. In the aftermath of Biko's murder the apartheid regime banned 19 BC organisations, The World, The Weekend World and Qoboza was detained without trial. | Graphic: Viasen Soobramoney

Image: Independent Media Archives

On October 19, 1977, when the South African Government carried out one of the most oppressive actions against the media by banning the Union of Black Journalists (UBJ) and 18 other anti-apartheid and anti-regime organisations, the security police also visited my home in Verulam in the early hours of that fateful day. The security police also conducted similar raids at the home of my then colleague at the Daily News, Mr Dennis Pather, and at the homes and offices of my colleagues of the UBJ in Johannesburg, East London, Port Elizabeth, Cape Town, and other major centres of the country.

Then, about two years later, on June 3, 1979, two “Indian-origin” members of the security police called at our home in Verulam and questioned me about the visit to South Africa by a journalist from Norway, Mr Olie Ericksen. Mr Ericksen was on a fact-finding mission for the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ), and I hosted him in Durban.

The security policemen questioned me for about one-and-a-half hours on Mr Ericksen’s trip and about the Writers Association of South Africa (WASA), which we, black journalists, had established after the Union of Black Journalists (UBJ) was banned by the apartheid regime on 19 October 1977. One of the security policemen was Major Benjamin. He was well known to be a notorious security police officer who followed and pursued with passion most of the activists at that time. Although being a person of Indian-origin, he failed to understand the struggles for a non-racial and free South Africa. He was more interested in serving the “white baas”.

But after 1994, when the ANC was elected to power, and Nelson Mandela was elected president, Major Benjamin became a member of the ANC.

There were many “turncoats” like Major Benjamin in the political and business world who also changed their costumes and colours and suddenly became staunch supporters of “liberty and freedom”.

After the visit of Benjamin and his colleague, the only other time the security police showed some interest in my work as a journalist was when I was in my second year as a full-time staffer at the Daily News in 1975.

Some of the members of the security police questioned a white colleague about me. They wanted to know: “Who is this Coolie journalist working in your office?”

They were apparently interested in me because of my regular and comprehensive reports on black trade unions and about the struggles of anti-apartheid sports organisations and their leaders.

On this particular day at the end of May 1980, De Beer and his colleague, after taking me into custody, drove straight to the offices of the Daily News at 85 Field Street (now Joe Slovo Street) in the centre of Durban. We took the lift to the second floor, where our newsroom was located.

Without speaking to anyone or obtaining permission, they just asked me to point out my desk. My colleagues looked on in shock and dismay. At that time members of the Security Branch of the police in South Africa were notorious for their brutality and no one, not even white citizens, dared to square up against them.

De Beer and his colleague began to search my desk and the drawers. They collected a pile of stories that I had written and put them together to be taken away.

Unknown to the security policemen, one of the Daily News photographers, Robert D'avice, snapped away at the action of the security branch policemen. This photograph was given to me after I was released from solitary detention.

The security policemen, thereafter, drove me to the Brighton Beach police station, near the Bluff on the outskirts of the city of Durban. Here, they spoke to a policeman on duty and then locked me in a cell. They did not say anything. They just left.

I was left to myself. All kinds of emotions ran through me. But in the end, I was sure that I did not commit any crime and the security policemen were just "fishing".

At about 9 pm that evening, Sgt De Beer and two other security policemen turned up at the police station.

"Mr Subramoney, we have come to take you to our office."

They drove me to their security police headquarters in Fisher Street (now Masobiya Mdluli Street) in Durban. Here I was given a notebook and told to write down my personal history - where I was born, who my parents were, which schools I went to, which organisations I belonged to, and where I worked.

After I finished writing what they wanted, they began to fire questions at me about my work: why was I covering the trade union movement? Why was I only concerned about black politics? And about non-racial sport?

"You. You are playing with fire. The white man has developed this country and coolies like you think we are just going to hand it over to the 'k…..s' (a derogatory term used by the white man at that time to describe black African people)," one of the security policemen shouted at me.

It was around midnight when they took me back to the police cells at Brighton Beach.

The next day, my first visitors were my cousin, Lutchmee, and her husband, Benny Reddy, who lived in the nearby township of Merebank.

My cousin was the second daughter of my mother’s eldest sister, Baigium. As a family, we were very close. When I was a little boy, I used to visit their home in the “tin town” area of Merebank regularly during the school holidays. I also, during my school holidays, travelled to Merebank by train and bus to sell the guava fruit to the residents. I collected the guavas on Friday afternoons from trees near the Ottawa River. I then used to, on a Saturday, travel by train to Durban and from there catch a bus to Merebank from the Warwick Avenue bus rank.

After we got married in February 1973, my wife, Thyna, and I stayed in an outbuilding at my cousin’s new home in Merebank. Early in the 1970s, my cousin, her elder brother, Soobiah, and their families moved into a council house at 16 Nagpur Place, Merebank.

My wife had informed them earlier that I was being held at the Brighton Beach Police Station nearby, and they should try to visit me.

The white policeman in charge knocked on the cell gate and said, "You have some visitors. You are not allowed any visitors, but I am going to allow them to see you."

I was surprised to see my cousin and brother-in-law. They brought me some lunch, for which I was very grateful. Before I could greet them, my cousin spoke with a lot of concern:

"Why are you getting into all this trouble? You are causing a lot of worry for everyone.

"You have a good job. Your wife and children are very young. Why do you have to get into trouble with the white man?" she asked with a great deal of anxiety in her voice.

I told my cousin and brother-in-law not to worry.

"I will be okay," I told them. But they were not too happy. They departed after giving me these words of advice: "Please be careful."

I went back to the cell and began to ponder life in general. Why was I here? How long am I going to be here? What are they going to do to me?

I found a pen on the floor and took it to the wall. I began to write: "Release Nelson Mandela and all your problems will be over."

I wrote this on almost every available space on the wall to pass my time.

Later that evening, when the security branch policemen came for me again, one of them blurted:

"Hey, look at what this Coolie journalist has been scribbling on the wall!"

"You are wasting your time. We are not going to let that terrorist out of prison. He will rot in jail," said the other security policeman.

"We have come to take you to our office."

They drove along the Brighton Beach road, through the Bluff, and along the main road to the city. The lights and the moving cars took my thoughts away from the situation I found myself in. I noticed some people walking along the roads - the working-class people who did not know what the security policemen in the country were up to.

At the security police headquarters, there were four security policemen seated around a table.

"Tell us what you guys are up to?" asked one of them.

"I see your people are making a lot of noise", said another. I did not know what he was talking about, but I learnt later that our Daily News editor, Mr John O'Mally, had made representations to higher authority about my detention and demanded that I be charged or released immediately.

I knew that the security policemen did not have anything against me. After accusing me of being a “terrorist”, “communist”, and warning me that I should watch my steps, they drove me back to the Brighton Beach police station at about 11 pm.

My news editor, Mr David James, insisted that I was not involved in anything illegal and reiterated that I should either be charged or released.

It was the same David James who, in June 1976, wanted to know where I had been on June 16 when the school children of Soweto had protested against the imposition of the Afrikaans language as a medium of instruction in African schools. I was away on holiday at that time, but he jokingly said:

"Hey Subry, you have been up to your tricks in Soweto!"

I knew he was just trying to “pull my leg,” and he did not mean anything.

I did not tell my news editor that I had, in fact, travelled to Soweto a few weeks after the June 16 uprisings to join Zwelakhe Sisulu, Joe Thloloe, Philip Mthimkulu, Ms Juby Mayet, Mathatha Tsedu, Thami Mazwai, Rashid Seria, and other colleagues from Port Elizabeth, East London, Cape Town, and Bloemfontein to launch the Union of Black Journalists (UBJ).

The UBJ, however, did not last long as the apartheid regime cracked down on the UBJ and 18 other anti-apartheid organisations on October 19, 1977.

Internationally acclaimed cartoonist Nanda Sooben (left) and veteran struggle journalist Subry Govender with a copy of Coolie Journalist. Sooben will be a guest speaker at the launch of the book on January 25, Umhlanga Apart Hotel, Durban.

Image: Supplied

Now three years later, in May 1980, while I was being detained, the security police demonstrated their brutality once again when they told me in no uncertain terms that they could hold me as long as they liked and the Daily News or anyone else could not do anything about it.

"We know you are an instigator. Wherever the children have been boycotting classes, we have seen you there. What were you doing, besides encouraging the children to stay away from school?" they asked accusingly.

"I was only doing my job", I protested.

"Please behave, Mr Subramoney. We don't want to see any more of your slogans on the wall", said one of them.

On the sixth day of my detention, Sgt De Beer and another security policeman arrived early. It was about 9 am.

"We are going to release you. But we are warning you, we are not finished with you."

They drove along the North Coast road from the city of Durban and dropped me off at home at 30 Mimosa Road, Verulam, at about 10:30 am.

My mother was overjoyed. She was carrying my daughter, Seshini, who jumped off and ran towards me. I picked her up and just held her for some time.

It was a great feeling to be back at home.

But the troubles with the security police had just begun.

** The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of IOL, Independent Media, or The African.