Chaos at COP: Lessons for Future Climate Negotiations

YEAR IN REVIEW

Oxfam activists wearing oversized masks representing (left to right) European Commission President Ursula Von der Leyen, Argentina's President Javier Milei, US President Donald Trump and Britain's Prime Minister Keir Starmer during their "Big Heads" protest at Utinga Park in Belem, Para state, Brazil, on November 20, 2025.

Image: AFP

Jonah Harris

Plenary meetings under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) are generally boring—a space for technical, formulaic statements. But the closing plenary of the recently concluded 30th Conference of the Parties (COP30) was anything but boring.

It saw a surprising feud between the COP30 president, Brazil, and its fellow Latin American countries, particularly Argentina, Colombia, Uruguay, Paraguay, and Panama. The divide was further heightened by Colombia’s active push for a roadmap to transition away from fossil fuels, something Brazil did not pursue with enthusiasm or insert into official texts.

Much of the climate negotiations is conducted through regional groups, and countries from the same region often support the presidency and help bring the outcome to the table. This time, the final plenary session revealed the opposite: a bitter war of words between countries that have historically collaborated on climate issues. The scene shocked and confused many observers.

Decision-Making in the UNFCCC

To understand why this chaos erupted, one must first understand the decision-making process within the UNFCCC. The COP and the meetings of the parties for the Kyoto Protocol and Paris Agreement (the CMP and CMA) all operate based on consensus.

Consensus is both a process and an outcome. As a result, it is a group decision not made through a formal vote. As a process, it is generally understood to require good-faith negotiation by parties to reach an agreement and, in the event of disagreement, the chance to put that disagreement on the record.

Once a disagreeing party has voiced its concerns and been heard, it is then asked to “step aside” and not block the final passage. A key figure in determining both the process and the outcome is the chair of the meeting, who must shepherd nearly 200 diverse countries to an outcome at least minimally acceptable to all.

In the UNFCCC, at least over the last several years, consensus has been defined generously: serious objections from one or two parties rarely hold up adoption. In almost every case, the president of the meeting is a representative of the summit’s host country and therefore motivated to achieve a political outcome, which comes with prestige.

In the plenary, the president will announce consideration of an item, look around the hall for objections, and then say, “Hearing no objections, it is so decided” while banging the gavel.

Despite deep divisions in climate diplomacy, official objections—or worse, calls for a vote—are rare to nonexistent for three reasons.

First, disagreements are typically negotiated behind the scenes outside the plenary hall, and if consensus is truly impossible, the president will decline to present a draft item for adoption.

Second, the consensus-driven nature of the negotiations means parties will often step aside rather than formally oppose items they dislike, understanding that the texts represent the will of the majority and that voting would be pointless and politically costly.

Finally, the parties continue to work on draft rules of procedure due to disagreement over whether formal rules should allow for votes in more circumstances.

Despite these norms, it is common for parties to take the floor before or after the adoption of an item they don’t like to express displeasure at the process or the outcome, or to state for the record how they interpret the language.

At the most extreme, speakers will use strong language to show that consensus has not been reached and that the item should not be adopted. A problem (and opportunity) for presidents is that the implications of such statements for consensus decision-making are often unclear.

A party may clarify that remarks are for the record only or decline to clarify, leading to uncertainty as to whether they intend to block passage. Further complicating the situation is the fluid definition of consensus and the ill-defined boundaries of a president’s power.

Nearly all agree that a single party’s opposition is not enough to break consensus, and past COPs are filled with moments when decisions were passed over angry opposition, with selectively deaf or blind presidents gaveling decisions through while ignoring desperate requests to take the floor.

Two Weeks of Negotiations

Every year, COPs bring tens of thousands of people together to discuss climate change. While there are thousands of official and unofficial events, at the core of the meetings are the intergovernmental negotiations, which result in a few dozen official decisions and resolutions.

Across two weeks, negotiations on different agenda items proceed in parallel in side rooms, as diplomats seek common ground while refining successive draft texts. This is always a race against time as country groups with highly varying priorities seek to influence the language. Negotiations inevitably lead to sleepless nights and drag on past the scheduled closing time—indeed, guessing how late summits will run has been a popular game in recent years.

In Belém, several issues were particularly contentious. Among them was a decision adopting a set of indicators for tracking progress toward the Global Goal on Adaptation (GGA), with countries disagreeing on the list of indicators, how work would proceed, and how to finance the process.

Equally difficult was a proposed roadmap on phasing out fossil fuels, something many countries pushed hard to include in final texts, but others fiercely opposed. As the hours before the final plenary ticked down, and as the plenary was pushed back time and again to accommodate last-minute negotiations, it was not clear to outsiders whether a deal had been struck on a package of texts that all could accept.

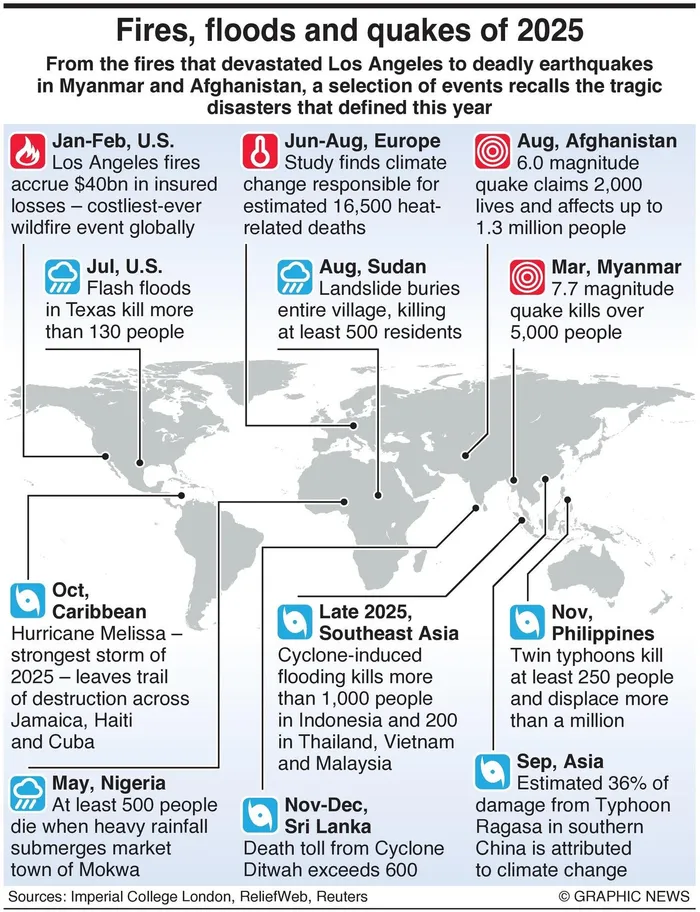

Environmental disasters in 2025.

Image: Graphic News

The Showdown

As the plenary commenced on Saturday afternoon, and as observers reviewed the draft texts, it was evident that many would be unhappy. The list of GGA indicators included items that had not been discussed in the multiyear negotiation process.

Moreover, the language on adaptation finance seemed calibrated to fulfill the adage of a compromise that leaves all equally unhappy. No fossil fuel roadmap was mentioned in the text.

Nevertheless, it was not clear whether any party would seek to block adoption. As the meeting began, the main texts—soon to be collectively named the Belém Political Package—were quickly gaveled through, with President André Corrêa do Lago moving from one adoption to the next with little visible pause to scan for objections.

Corrêa do Lago also announced that the presidency would undertake a fossil fuel roadmap and a second roadmap on deforestation under its own auspices—only a partial consolation to parties that sought references in the official texts. The last item to be given was the Mitigation Work Programme.

In formal meetings, parties and other actors request opportunities to address the plenary by communicating with the presidency or secretariat. While such requests are sometimes prearranged, at other times parties simply raise their hand or nameplate to indicate their desire to speak.

It is the responsibility of the president and secretariat to scan the hall at appropriate times to check for requests. Parties may also raise a point of order—an urgent request to bring the presidency’s attention to a procedural issue, signaled by raising both arms with fingers touching in an inverted V. A point of order must relate to procedure and cannot be used for a normal statement, but the presidency is expected to address it immediately rather than wait for a later opening.

As soon as the final text was gaveled, the chaos began. Numerous countries lodged complaints about how the plenary had unfolded. Upon being given the floor, Panama noted that a request to speak—and a point of order—had been ignored before the GGA was adopted, but that they would not hold up adoption.

Uruguay, speaking also on behalf of Argentina, Ecuador, and Paraguay, made a similar complaint, later calling a point of order and explicitly rejecting the premise that the text had been passed by consensus.

Colombia noted that a point of order had been ignored before the adoption of the MWP and rejected passage unless a paragraph referencing the transition away from fossil fuels was added; it also supported Panama and Uruguay. Canada emphasized the need to examine the points of order and asked for language changes, while other parties criticized the texts without blocking them.

While the line for how much opposition can be swept aside is unclear, it had evidently been crossed, and the situation was further complicated by the contested or ignored requests for the floor before formal adoption. The president suspended the meeting, and clamor arose from all quarters. On the dais, the presidency and UNFCCC secretariat began to urgently confer.

The immediate question—one the secretariat was best equipped to answer—was technical and legal: were the objections strong enough to prevent or undo passage of the given decisions? Had those items actually been approved? How would a ruling affect the rest of the climate regime?

Amid the widespread uncertainty and lack of sleep, some veteran observers speculated that a precedent of allowing objections to undo given decisions could be used by parties to call decisions into question.

India had notably strongly objected with emphatic language after last year’s headline passage of the New Collective Quantified Goal on climate finance (NCQG), also complaining that its request for the floor had been ignored before adoption. It appeared at least possible (albeit unlikely) that the summit could crash hard enough that the damage would spread backward to decisions whose ink was long dry.

Beyond this technical and legal quandary, and perhaps more immediately, there was the question of how to address the substance of the objections. The parties raising points of order had actionable requests on the GGA and MWP texts, but accepting them would invite objections from other parties and reopen difficult negotiations that—at least in the mind of the presidency—had reached their best possible landing zone.

After a tense hour, news spread that the secretariat would apologize for not seeing the nameplates, but that—to avoid the nightmare scenario of reopening past COPs—the texts would not be “ungaveled” or amended.

Parties’ objections would be reflected in the upcoming official report on the proceedings, and steps would be taken to avoid a repeat. The plenary reconvened, and a tired-looking Corrêa do Lago apologized and explained the compromise to the confused delegates. The fireworks over, the plenary continued for another few hours, adopting technical items and hearing statements from parties and observers before the summit was finally gavelled to a close.

Lessons for Future Negotiations

The public discord in the final plenary offers useful lessons for UNFCCC negotiators. Watchers were given clear examples of the potential for confusion due to the vagueness of concepts such as consensus and presidential authority.

At the same time, agreeing more precisely on the scope of the presidency and on how decisions should be made is unlikely: COPs are still operating on provisional rules of procedure because the parties have not been able to agree on these for 30 years. These concepts will thus remain nebulous. The lesson is that strategic, intentional leadership is needed to shepherd concrete outcomes through the process.

The secretariat’s pledge to examine how to avoid a repeat will be helpful. But if the main takeaway for future presidencies is simply to spend more time scanning the room before gaveling, the root cause of the showdown will remain unaddressed.

Presidencies need to spend the days, weeks, and months before taking their seat on the dais preparing. These preparations should involve parties from every region and negotiation grouping, and should involve writing and refining language as soon as possible. Neither two weeks nor two hours is enough time to discuss edits with all relevant parties, and it is inevitable that at such a frenetic pace, such fault lines will resurface.

Finally, COP30 was the first summit where the presidency prioritized discussions on “arrangements for intergovernmental meetings.” In this workstream, diverse stakeholders discussed ways to improve the UNFCCC’s COP process. While there were few concrete outcomes, these talks should continue and should address both the direct and the indirect causes of the final plenary issues.

The essential work of diplomacy takes place behind the scenes and involves patience, resolve, leadership, and optimism. Just as engineers study failures to design better machines, negotiators should seek to understand what led to the chaos to prevent it in the future.

By reflecting on and discussing arrangements for intergovernmental meetings, negotiators can help ensure that the UNFCCC can remain relevant and continue to secure concrete outcomes that benefit people and planet.

* Jonah Harris is a Policy Analyst in the Peace, Climate, and Sustainable Development Program. This article was originally published at https://theglobalobservatory.org/

** The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of IOL, Independent Media or The African.