Remembering Titus Mafolo: A Tribute to an Afrocentric Visionary and Selfless Cadre

TRIBUTE

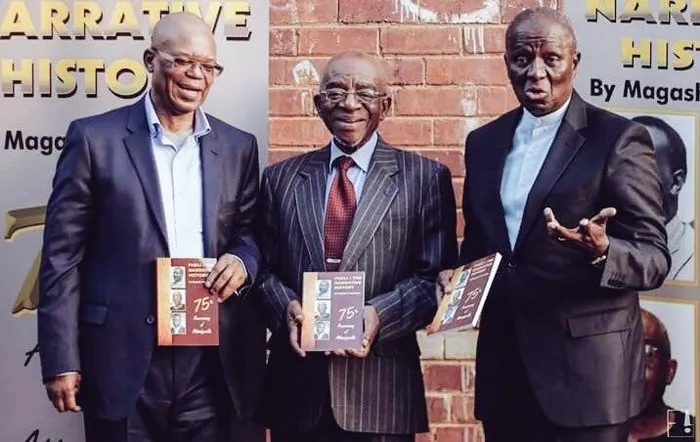

Struggle veterans (from left) Titus Mafolo, late Dr. Abe Nkomo and former Deputy Chief Justice Dikgang Moseneke. To Mafolo, Africans are not spectators of history but active participants shaping it and constantly determining their future, says the writer.

Image: X

Eddy Maloka

We were unprepared for the sudden passing of our dear friend and comrade, Titus Mafolo, after a brief illness. Ti, as he was affectionately called, can be described in various ways.

An “outie” from Atteridgeville, a township in Tshwane known as “Pheli” by its residents. His Atteridgeville roots were evident not only in the circle of friends he associated with but also in his local dialect, which blended pidgin Sesotho with a mix of Afrikaans.

To others, Mafolo will be remembered as a veteran of the erstwhile United Democratic Front (UDF). During those difficult years of our struggle, he suffered incarceration, torture, and banning orders like many of its leaders, but was never deterred. He prevailed, outlived his oppressors, and was among the first contingent of ANC members deployed to the parliament of democratic South Africa.

We can also describe Mafolo as a trusted advisor to President Thabo Mbeki during the vibrant years of the African Renaissance. I was told then that Mbeki trusted Mafolo’s writing skills so much that he would confidently take a speech drafted by him to deliver it without worrying much about proofreading it first.

In this tribute, I want to emphasise one trait that fuelled his passion – his steadfast Afrocentric outlook on life and his environment. He applied this perspective not only in his epistemological bias, or in his views on culture, but also to street names.

He was a leading figure in the movement to rename Pretoria as Tshwane. Those of us who took time to adapt to the new name would be promptly corrected during a casual conversation and provided with a lecture on the history of Tshwane.

A few years ago, when I led the Africa Institute of South Africa, Mafolo invited me to join a new organisation called The Native Club. While the club had modest goals, it sparked unexpected controversy.

In June 2006, The Guardian published an article titled “South Africa’s ‘Native Club’ stirs unease,” questioning: “Based at the Africa Institute in Pretoria, the club has garnered praise, ridicule, and uneasy questions: Who are its members? How influential are they? What defines a native?” Mafolo replied, “Although we are Africans, many South Africans seem to have an identity crisis. Our clothing, music, cuisine, role models, and references suggest we are copies of Americans and Europeans.”

His Afrocentric perspective, coupled with his background as a political activist, placed emphasis on African agency. To Mafolo, Africans are not spectators of history but active participants shaping it and constantly determining their future. He expressed this conviction through his passionate writing, like in his book Pheli – A Narrative History (2015), which chronicles the history of his beloved Atteridgeville.

During its launch in 2015 at his former high school in his hometown, he told his audience, “I am tired of people telling our story. It is time we wrote our own history… I do not think anyone else could write what I wrote because I was there. Why can’t I be one of the primary sources myself?”

He did not stop there. A few years later, he published his African Odyssey trilogy (2020), a three-volume epic history of Africa. Through this trilogy, Mafolo sought to expand on the work pioneered by the likes of Cheikh Anta Diop in African Origin of Civilization, Martin Bernal in Black Athena: The Afroasiatic Roots of Classical Civilisation, and George James in Stolen Legacy: Greek Philosophy is Stolen Egyptian Philosophy.

Such an intellectual pursuit is demanding, given the numerous books to read and the deep knowledge required. Nevertheless, Mafolo took on this challenge with impressive ease. The only headache that he constantly complained about was the length of his manuscript, which he then divided into three volumes.

He just couldn’t stop writing. As he departs, he has left us two unfinished manuscripts that he was working on simultaneously. I don’t know how he managed that. One of them is on the heroes and heroines of Tshwane.

We will miss him as his friends, especially his subtle sense of humour. But the ANC has lost more. He was constantly worried about the future and direction of this movement, to which he dedicated his entire adult life. Always ready for an ANC assignment, he never complained, nor sought recognition or reward. His Afrocentric passion kept him grounded, being a selfless cadre among his people.

* Eddy Maloka is a friend of the Mafolo family.

** The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of IOL, Independent Media or The African.