The Legacy of a Fearless Activist in South Africa's Democratic Journey

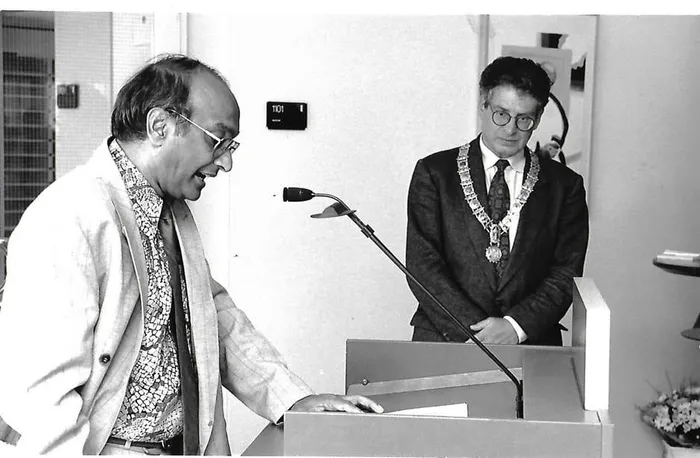

ANC veteran Sunny Singh with the Mayor of Amsterdam Van Thyn at the opening of the ANC's Netherlands office in the 1980s.

Image: Subry Govender

Ivan Pillay

Sunny is one of those rare persons who eschew self-interest. He placed others before himself and the nation above all else. I would like to share those parts of his story that I was fortunate enough to know about.

As activists, before we met Sunny, we had tried without much success to connect with the underground ANC. We had met with members of NIC, SACTU, and CPSA from the 1950s and 1960s. Most were then not active. This was the early 1970s. Fear of the Security Branch, fear of arrest and detention, and imprisonment was palpable. I first heard of Sunny from an acquaintance who donated to a quarterly publication we produced as a group in Merebank, “The Sentinel”.

Concerned that I may get myself into trouble through political activism, this acquaintance told me about his schoolmate who had been jailed on Robben Island, had been released, was banned, and was jobless, as a cautionary tale. So naturally, I asked for an introduction.

In the meantime, despite his banning orders, Sunny was in the process of engaging various community activist groups in the townships. Regular meetings took place with, for example, those around Bobby Marie in Merebank, Anban Govender, who was active in the Chatsworth area, Terrence Tryon, who was also banned, Shamim Meer, and Pravin Gordhan.

The meeting with Sunny was what some of us were waiting for.

It wasn’t long before Sunny drew us into his orbit. My brother Joe, the late Patrick Msomi, the late Krishna Rabilal, and I joined the ANC. Sunny left the country just before the introduction of legislation that would enable the regime to detain large numbers of people without the need to take them to court: the Internal Security Act.

After the arrest of the late Shadrack Maphumalo, to whom they were linked, Pat and Joe left the country in about May 1977, and I followed in July 1977. I next met Sunny in Angola in a camp in Funda. There, two IRA commanders were training a small group, including Joe and Sunny, in urban guerrilla warfare.

Quite rightly, he was disappointed to see me! Sunny had hoped that I would have lasted longer inside the country. A few months later, as instructed by the ANC, Joe and I surfaced in Swaziland, where we registered ourselves as refugees. Sunny was deployed to Maputo. We were all part of MK structures.

In Swaziland, we linked up again with Pat Msomi and Jabu. They were both active in SACTU, and Pat was, in addition, involved with intelligence and security. Sunny and I were members of MK. We were, moreover, critical members of MK. Influenced by pamphlets and books on the struggles of the Philippines, Latin America, and Amilcar Cabral in Guinea-Bissau, we regularly raised our concern that MK was not operating like a political army.

There was little or no ANC political underground work that concretely linked with armed activities inside the country, nor with the mobilization and organization undertaken by communities and the trade unions. Furthermore, our losses were too numerous for a guerrilla army. Eventually, in 1979, changes were made. Not exactly in the way that some of us had wished for. But it was a step forward. In what would become a typical ANC response, a new structure was formed –the Internal Political Reconstruction Committee.

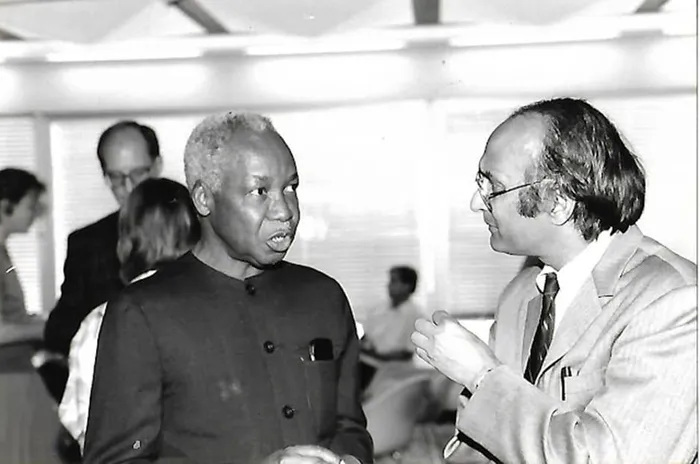

Then Tanzanian President Mwalimu Julius Kambarage Nyerere in discussion with Sunny 'Bobby' Singh at The Hague, Netherlands in the late 1980s.

Image: Subry Govender

That committee was headed by John Motsabi, and Mac was its Secretary. Both Sunny and I became part of this new structure, he in Mozambique and I in Swaziland. Botswana, Lesotho, and Swaziland were what we referred to as forward areas, as in the Southern African situation, neighbouring territories of South Africa could not be classical rear bases. Mozambique provided a limited rear base capability. Our senior regional leadership was located in Mozambique and provided direction, analytics, and training support.

Despite the limitations, cadres and weapons were smuggled from further north through Mozambique into Swaziland and into South Africa. At least four or five times a year, we jumped the fence into Mozambique to go to our Maputo headquarters, Internal House, in transit to elsewhere, and or consultations. I always stayed with Sunny in his flat. The lift didn’t work. Food was scarce. It may be difficult to imagine what that was like. There were no fast food outlets. When you were hungry, even if you had money, you couldn’t just go to a cafe. Most retail spaces were boarded up.

The Government provided rationed goods to its citizens. Citizens planted vegetables on every available piece of land to avoid going hungry. ANC provided rations and small allowances to its cadres, but these were very basic. Anything more, you would have to get from dollar shops, but these shops only accept foreign currencies.

Sunny, a notable networker, knew where to go.

On the fateful day when the suburb of Matola was attacked, I also happened to be in Maputo. That night, some alerts had been received about strange movements in Matola. Hours later, we received the tragic news that eleven people were killed, including the Head of the Natal MK command, Mdu, and one of the members of his team, Krishna Rabilal. We had lost comrades. We had also lost a friend, a simple, unassuming, dedicated patriot. More bad news was to follow.

Joe was kidnapped from Swaziland, taken to South Africa, and interrogated. Pat Msomi, who was part of the ANC’s security and intelligence capacity, worked tirelessly to accumulate bargaining chips while an international campaign to release Joe was initiated with the help of Dutch, English, and American aid-workers.

The first chip was a dompass that one of the kidnappers dropped in the scuffle when they overpowered Joe.

The second, the clincher, was the arrest some days later of some of the kidnappers who were based in Swaziland. A witness to the scuffle recognized some of the kidnappers in a street in Manzini. They were part of Renamo, an anti-Frelimo movement that was supported by the apartheid regime.

A few weeks after the arrests, a blindfolded Joe was dumped in Mbabane, while the Renamo members were released, probably to the South African authorities. Cadres in Swaziland were under continuous threat of attack from the SA security forces. Most of us lived incognito, travelling at night. Joe was vulnerable because he was a teacher who stayed in accommodation provided at the school.

Pat Msomi and his wife Jabu were also vulnerable. They had four children, three of whom were attending school. So, although they did take precautions, they could not be incognito. The SA security forces murdered Pat and Jabu. They booby-trapped their vehicle, which was parked outside a “safe” flat. The three surviving children are based in the Pietermaritzburg area. Pat and Jabu received posthumous awards in 2016.

Occasionally, Sunny came to Swaziland, crossing the fence. I will always remember a particular trip when Sunny, having completed his mission, bade farewell to us at about three o'clock in the morning as we moved to his rendezvous point. He was picked up by two comrades. They would drop him at a safe distance from the fence at Nomasha. Once over the fence, he would walk to a safe house. If there were also cadres crossing from Mozambique to Swaziland, then he would be escorted to the safe house.

Later that morning, Joe and I were surprised by Sunny at the door; he was fuming with anger and disappointment. On their way to the border, in the dark, a buck ran across the road. The comrades stopped the car and are insistent that this was a bad sign. They will not continue. They have to abort the mission.

He shakes his head-“we have a long way to go”. That experience makes me recall an earlier incident in South Africa. Comrade Dip was due to be released from prison. With the help of comrades, we had the house cleaned and painted. Sunny wanted me to give Dip a message. So I was safely waiting in Dip’s spruced-up little house while the family and friends went to receive Dip and bring him back home.

As is customary, Dip’s wife made him sit on a chair near the entrance outside the house and recited a prayer while turning an oil lamp three times clockwise and then three times anticlockwise and finally up and down vertically. From my vantage point, I could see and hear a visibly irritated Dip. He muttered his displeasure. “I am a man of science.”

Sunny attended the first congress of the SACP in 1984 in Moscow. Among other matters, the issue of whether the ANC leadership (the NEC) should be open to all South Africans was debated. It boggled our minds then that leading Party members could countenance the notion that the NEC could be restricted to “Africans”.

As Sunny pointed out at the meeting, not long ago, tens of thousands of mainly black people had marched to demonstrate their defiance of the security forces who had murdered Neil Aggett. In the end, the SACP resolved to support the view that the ANC should be open to all. There, we witnessed the tug of war for the soul of the Party. We celebrated the victory of the progressives that ushered in perhaps the most successful years of the Party in exile.

A strong Politbureau was elected. The Party machine became more efficient and effective. Umsebenzi, which addressed current events as they unfolded, was regularly published. More Party units were created and operated inside South Africa. When the Second Party Congress was convened in Cuba, comrades from Party structures in South Africa were present.

Shortly thereafter, the Nkomati accord between South Africa and Mozambique was signed. Sunny and many others who were formerly resident in Mozambique were forced to resettle in Zambia. Scores of cadres who operated clandestinely in Mozambique had to hastily move into Swaziland to avoid being rounded up and deported to Tanzania. The resultant build-up of our forces in tiny Swaziland led to tensions with Swazi security forces.

The apartheid state, using Askaris, multiplied its attacks and kidnappings. We lost many experienced cadres. Among them were Cassius Make, a member of the NEC, and Paul Dikeledi, a member of the Regional Political Military Committee. Both were well known to Sunny.

ANC President Oliver Tambo, Thabo Mbeki and Alfred Nzo address a press conference following the party's historic National Consultative Conference held in Kabwe, Zambia. Sunny Singh attended conference where the ANC decided to open its leadership to all races, says the writer.

Image: AFP

Sunny also attended the ANC conference in Kabwe. It was historic for at least three reasons:

1) OR briefed delegates that some South Africans wanted to talk to the ANC. At that stage, it was a group of businessmen. He asked for a mandate, which he was given to meet such groups. That marked the beginning of many meetings between civil society organisations and the ANC and perhaps laid the foundation for a negotiated settlement.

2) It was resolved that the leadership of the ANC cannot be restricted to Africans only, but it must be opened to all. The first non-racial NEC was duly elected.

3) Hitherto, MK avoided attacking targets that would lead to the death of civilians. It was decided that while it was not our intention to attack civilians per se, we would no longer avoid a legitimate military target if there might be loss of civilian lives.

In mid-1986, I was redeployed to Zambia, where I linked up with Sunny once again. Zambia is different from Swaziland, Mozambique, and the other forward areas. It is the headquarters of the ANC. There are many ANC people there and a considerable infrastructure. Branches of the ANC, called Regional Political Committees, existed and operated.

Sunny was then a part of the Department of International Relations and was awaiting his deployment to the Netherlands to open the first officially recognized ANC office there. While in Zambia, he was helpful to Operation Vula as he provided logistical support to us. When we returned from exile to South Africa, Sunny was deployed as a colonel in SAPS until his retirement.

While life in exile, even in Southern Africa, was less restrictive than operating inside South Africa, some comrades did lose their orientation. Not Sunny. Sunny led the way. He was and is always ethically grounded. Many ex-prisoners told us that Sunny was a critical part of the news and information value chain on Robben Island. Indres Naidoo’s book captures that well.

In the recent years, Sunny was deeply committed to the Monty Naicker Foundation in building awareness of our history and in building a democratic South Africa. Sunny lands on his feet in any situation and is always moving forward. He is the reason that some of us joined the ANC. And his example is a reason that some of us have questions about the ANC of today. But as Sunny shows, what matters is that we are not paralysed, that wherever we are, we take practical steps to strengthen our democracy.

* Ivan Pillay is a ANC and SACP veteran.

** The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of IOL, Independent Media or The African.