Khampepe Probe's False Start Heightens Apartheid-Era Victims' Cynicism

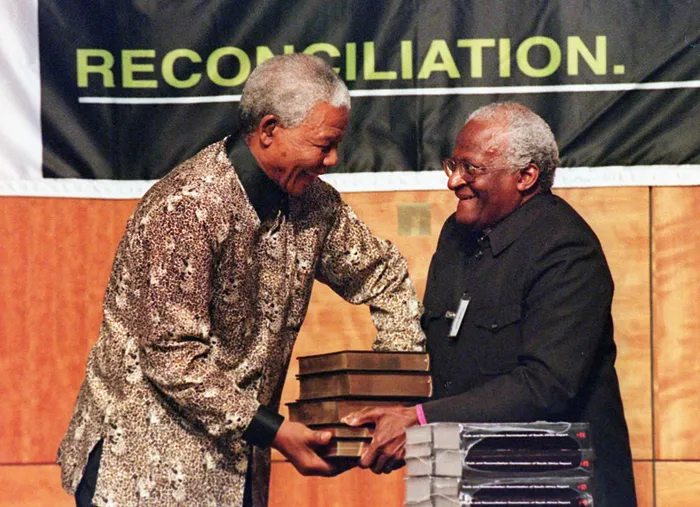

President Nelson Mandela receives five volumes of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) final report from Archbishop Desmond Tutu, in Pretoria on October 29, 1998.

Image: AFP

Prof. Bheki Mngomezulu

In May 2025, President Cyril Ramaphosa invoked Section 84(f) of the Constitution of South Africa, which states that a sitting president is responsible for “appointing commissions of inquiry.” This is the section that empowered the president to sign a proclamation for the establishment of a commission of inquiry to determine whether any attempts were made to prevent the investigation and subsequent prosecution of apartheid era crimes.

Retired Constitutional Court Judge Sisi Khampepe was appointed to chair this commission. Her assistants were retired Northern Cape Judge President Frans Diale Kgomo and Advocate Andrea Gabriel SC.

All three individuals are grounded in law and thus do qualify to serve in this commission. But the question arises: was the appointment of this commission justifiable? Were there no other mechanisms to establish the facts through normal legal channels using already existing state institutions? Are commissions being used to employ retired judges, or are they based on substance?

Given the country’s financial position, does it make sense to appoint one commission of inquiry after another each time the country needs to establish what happened on certain issues? What are office bearers in relevant units being paid for if they cannot conduct investigations and table findings to the National Prosecuting Authority (NPA) to carry out its mandate? These and other questions beg for attention.

A straight answer to the first question is that the country does not need another commission of inquiry. Signing the proclamation, President Ramaphosa argued that “for many years there have been allegations of interference in these cases,” thus resulting in delays in the investigation and prosecution of brutal crimes committed during apartheid. He continued to say that “this has caused the families of victims great anguish and frustration.”

Factually, the president was right. However, this is not a justification for or a reason to warrant the appointment of a commission of inquiry. A simple allegation like this one could be easily investigated by people already working within the justice system.

Appointing a commission of inquiry will cause another unnecessary delay. Firstly, by their very nature, commissions of inquiry do not have prosecutorial powers. All they do is collect evidence, compile reports, and make recommendations. Whoever receives the commission report (in this case, the president) will still tell the nation that he is studying the report, which will take some time.

Once he has studied the report, referrals would be made to the NPA to establish if reported cases have a chance of successful prosecution. This takes another time. The next step would be to enrol those cases and have dates assigned to them. Where additional information is required, there would be an adjournment to allow investigators to conduct further investigation. So, if these investigators do exist, why not give them the task to carry out the initial investigation, which must be done by a commission? This would save the state time and money.

This leads to the other question about how we use commissions of inquiry. Are we genuine in appointing them, or do we do so to create employment for our retired judges? If the latter is the case, what are we saying about service delivery protests and the increasing national debt?

The president was right in saying that “all affected families – and indeed all South Africans – deserve closure and justice.” But will that closure be best served by a commission of inquiry or a thorough, proper investigation carried out by incumbents in the system?

If the argument is that the judiciary cannot be trusted due to alleged infiltration by outside elements, when did such infiltration begin? If it has been there for some time, were the now-retired judges not implicated? If the answer is “no”, then there is optimism. However, if the answer is “yes”, then we have another serious problem which might cast doubt even on the recommendations they make.

My suspicions about the possibility of a long, drawn-out process are buttressed by the president’s own statements. He clearly and confidently stated that “a commission of inquiry with broad and comprehensive terms of reference is an opportunity to establish the truth and provide guidance on any further action that needs to be taken.” The fact that terms of reference are meant to be “broad and comprehensive” means that the process might take longer.

Secondly, the fact that the commission will recommend “further action that needs to be taken” means that the conclusion of the work of the commission will not provide the families of the victims and South Africans the truth they are yearning for. Instead, when the work of the commission ends, another process (or processes) will ensue. As the president stated, the commission will cover the period from 2003 to date.

If we take cases related to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) alone, we can see that the Khampepe commission has its work cut out. Once we add other cases, the situation gets even more complex. Families of the Cradock Four, Chief Albert Luthuli, Jameson Ngoloyi Mngomezulu, the Mxenge family, Steve Biko’s family, and many others may have to wait for much longer. Yes, the inquests that have been carried out in KwaZulu-Natal regarding the Luthuli and the Mxenge family matters have assisted a bit. But the country and the victims’ families still need more answers.

The TRC was established in 1995 following the passing of the Promotion of National Unity and Reconciliation Act. On October 29, 1998, the TRC submitted its first five volumes. The other two volumes were submitted on March 21, 2003, to coincide with the Human Rights Day – hence the commission’s starting date is 2003.

Between that time and now, many perpetrators have died. Adjourning the sitting to November 26, 2025, reduces any chance of getting to the truth of what happened. As the saying goes, ‘justice delayed is justice denied.’ Are we not doing that through these commissions?

Based on the above, my view is that there is no justification for the Khampepe Commission.

* Prof. Bheki Mngomezulu is Director of the Centre for the Advancement of Non-Racialism and Democracy at Nelson Mandela University.

** The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of IOL, Independent Media or The African.