What Is the State of Play of Climate Commitments Heading into COP30?

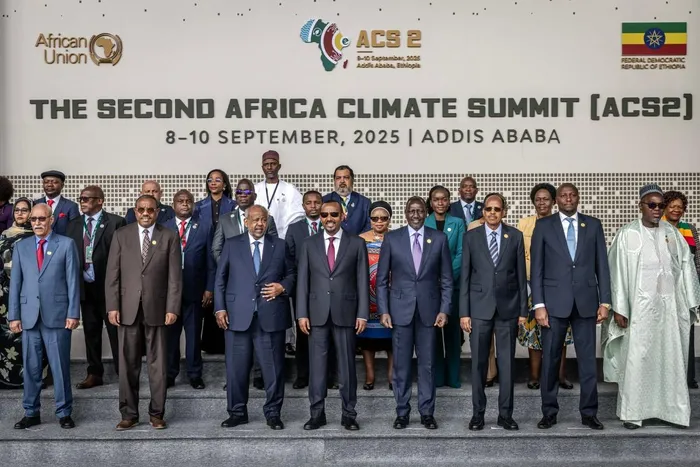

African heads of state and government representatives during the opening of the High-Level Leaders Summit at the Second Africa Climate Summit (ACS2) in Addis Ababa, on September 8, 2025.

Image: AFP

Jonah Harris

The 30th Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP30) is fast approaching. In Belém, where the Amazon River meets the Brazilian coast, diplomats must agree on a package of outcomes that keep the goals of the Paris Agreement within reach.

The Paris Agreement, signed in 2015, centers on nationally determined contributions (NDCs), which are nonbinding pledges that outline domestic climate targets. Per the agreement, NDCs should be communicated every five years, represent the highest possible ambition, progress over time through the “ratchet mechanism,” and respond to a series of global stocktakes that monitor collective progress.

This is a pivotal year for the NDCs. States are required to submit enhanced pledges—so-called NDCs 3.0, following the initial pledges around the signing of the Paris Agreement and a second round in 2020. These NDCs are meant to respond to the first global stocktake, which concluded in 2023, and set targets for 2035.

Despite an initial February deadline, then a revised September deadline, most countries are worryingly behind schedule on submitting their NDCs. September’s General Debate at the UN General Assembly and the secretary-general’s Climate Summit were expected to kick things into gear: the submission or announcement of climate targets, in particular from major emitters, were among the most eagerly anticipated elements. However, the limited number of new commitments and the lack of ambition of new pledges disappointed observers.

A Worrying Lack of Ambition

Although more than 150 heads of state and government mentioned climate change in the General Debate, and about 35 participated in the Climate Summit, the number of new NDCs submitted and announced was underwhelming.

China’s pledge at the Climate Summit received by far the most attention. Due to its enormous population and industrial capacity, it accounts for 30.1% of contemporary global GHG emissions and 90% of CO2 growth since the signing of the Paris Agreement—2.7 times as much as the next largest emitter, the United States; 3.9 times the emissions of India; and 5 times the emissions of the European Union. For this reason, China’s actions can singlehandedly make or break the pathway to 1.5°C.

The highlight of China’s pledge, as outlined by President Xi Jinping, was to reduce GHG emissions 7–10% from an undefined peak year by 2035. Civil society assessments had previously held that China needed to reduce emissions by 30% by 2035 to align with the 1.5°C pathway, and the announced numbers were widely derided as critically insufficient.

Beyond China, several countries also announced or reintegrated pledges at the Climate Summit. Brazil reaffirmed its 59–67% economy-wide reduction target; the United Kingdom pledged an 81% reduction of GHG emissions from 1990 levels—the first major economy to go beyond 80%; and the EU proposed raising its ambition from 55% to 66–72%, pending member state approval. Australia pledged a 62–70% reduction from 2005 levels, Norway promised a 70–75% reduction from 1990 levels, and Russia promised (and later officially submitted) a plan for a 65–67% reduction from 1990 levels and carbon neutrality by 2060.

Nigeria and Bangladesh outlined NDCs they had already submitted to the secretariat of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), while Mexico, Tanzania, and South Africa indicated that their next NDCs were being drafted but did not provide details.

Civil society reactions to the NDCs were negative, focusing on the limited number of finalized NDCs, the weakness of China’s target, and the lack of detail from important mid-level emitters like India, Indonesia, Mexico, and the Republic of Korea.

The forthcoming NDC Synthesis Report, which aggregates all pledges, is likely to assess that current commitments still place the world on a trajectory to exceed 2.0°C in warming: progress from 2.6°C, but not nearly enough.

The absence of US participation in the Climate Summit under President Donald Trump reinforced the sense of disengagement by the world’s largest economy—an absence all the more striking given the personal intervention by China’s President Xi (even if via video). The COP presidency will now hold consultations on a response to the pledges and on other key topics.

The Path Forward

To get back on track, countries that have not submitted NDCs need to do so, and all need to raise the ambitions of their commitments. In the 2015 Paris Agreement, countries agreed to “holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C.”

Since then, the latest scientific evidence has underlined the importance of the more ambitious goal. Small island developing states (SIDS) and other vulnerable countries have consistently pushed for broader policies aligned with 1.5°C rather than 2°C.

These efforts were given a major boost by a recent advisory opinion by the International Court of Justice (ICJ), which found that states have a legal obligation to act consistently with the 1.5°C target—a positive development in international climate law. This opinion only emphasizes the importance of ambitious NDCs 3.0 and underscores the cost of the current global indifference.

Higher ambition is particularly needed from the highest emitters. China’s scale gives it unique leverage over global outcomes. Yet despite the low promise of a 7–10% reduction, there is a glimmer of hope.

Historically, China has tended to make conservative commitments and overperform, especially given its leadership on renewable energy. Analysts from the Asia Society noted that expanding China’s solar and wind resources to 3,600 gigawatts—a figure mentioned by Xi as an aspirational goal—could alone reduce power generation from coal by 20%.

President Xi’s language hinted that a higher target might be within reach. To achieve that, an intervention by Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva to engage China and reaffirm the importance of a strong COP outcome for the BRICS and the Global South could go a long way.

Despite the disappointing NDCs, the Climate Summit also revealed promising avenues for progress. For example, numerous world leaders mentioned methane reduction as a policy priority. As the secretary-general highlighted, about 40% of contemporary methane emissions from fossil fuel infrastructure can be cut with zero net costs, and there are also quick and cheap ways to reduce methane emissions in other areas.

Yet meeting these goals requires more than just commitments on paper. Countries must ensure that there is sufficient financing to meet the targets in a timely manner. Estimates vary widely, but there is consensus that trillions of US dollars must be mobilized before 2030 to meet current targets alone, well above the current NCQG, which sets differentiated targets of $300 billion and $1.3 trillion. Without predictable and scaled-up financing, even the most ambitious commitments still fall short of the 1.5°C goal.

With only weeks remaining before COP30—the conference that may make or break the 1.5°C target—there is no time to lose.

* Jonah Harris is a Policy Analyst in the Peace, Climate, and Sustainable Development Program. This is an edited version of the article originally published at https://theglobalobservatory.org/

** The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of IOL, Independent Media or The African.