‘Rockets streaking through the night sky’

BOOK EXTRACT

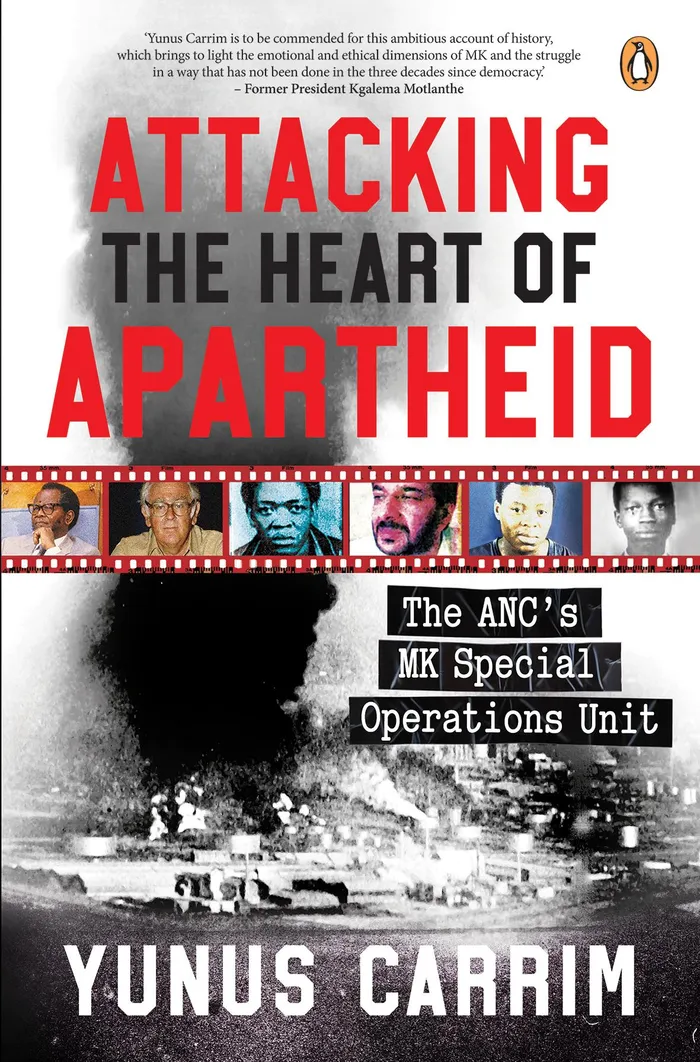

Former ANC Member of Parliament Yunus Carrim narrates the untold stories of the ANC's MK Special Operations Unit.

Image: Supplied

Blurb:

For over three decades, the remarkable story of Umkhonto we Sizwe’s Special Operations Unit has remained largely untold. Formed under the direct command of ANC president Oliver Tambo and senior ANC and SACP leader Joe Slovo, this elite unit executed some of the most daring and high-profile attacks against the apartheid state in the 1980s. In this groundbreaking book by ANC and SACP activist Yunus Carrim, the history of Special Ops is brought to life through the voices of its surviving participants. This is an account of the unit's daring attack on the SADF's militray fortress Voortrekkerhoogte.

Between 22:30 and 23:00 on 12 August 1981, five 122-mm rockets from a Grad-P rocket launcher, used for the first time in South Africa, hit Voortrekkerhoogte, the main SADF base in the heart of Pretoria.

The blasts were heard all over the city’s southern and eastern suburbs.

A resident described the loud noise as “a grinding sound, like the sliding door of a panel van being opened”. He rushed outside to see rockets “streaking through the night sky”.

Zora Ahli saw “four streaks of flame, one after the other, rising from open ground to the west, flashing right over her house moving eastwards. She likened the phenomenon to four shooting stars.”

It’s not clear exactly what was hit. A rocket certainly hit the house of a domestic worker. The other rockets hit a pillar of the military college, an ablution block, an open field, and one or two houses. One rocket seems to have failed to explode.

Another cut through the corrugated-iron walls of a garage, went through a storeroom, passed between the storeroom and the domestic worker’s room, struck the ground, and detonated. The force of the blast dislodged the roof of the room, burst the windows and toppled furniture.

“All I could see was fire … I just heard ‘bam’ and saw fire all over my room,” said Elsie Sekanka, the domestic worker. She scrambled out of the burning room and climbed through a broken window.

The army was taken completely by surprise. They mounted a massive search for the perpetrators. They erected roadblocks throughout the Transvaal and searched cars and people. Entrances to Atteridgeville and Saulsville were blocked, and Soweto was cordoned off.

Police in camouflage uniforms boarded the morning trains and searched commuters.

Commissioner General Johann Coetzee said that the attack was “a significant event because it had a psychological effect on the government by striking at the heart of its military forces”. The regime retaliated by bombing the ANC office in London

The attack took place during the twentieth anniversary celebrations of South Africa becoming a republic. Coincidentally, it was also Budget Day, but the Voortrekkerhoogte attack overshadowed this.

The operation was carried out by the ANC’s Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK) Special Operations Unit. The operational commander of the attack was Barney Molokoane, and the others in the unit were Johannes Mnisi, Johnny Mashigo, Vincent Sekete and Velaphi Mbele.

Getting their ducks in a row

Secluded among blue gum trees in Erasmia, a white area of Pretoria, was

a smallholding, “Mooiplaas”, with a five-roomed farmhouse. It was about 600 metres from the police station.

In June 1981, Nicholas Heath and Bonnie Muller, a British couple, rented Mooiplaas for R500 a year from Gerhard Basson. They said they were married and wanted to relax in South Africa as Heath recovered from ill health.

But they were not married. Nor was Heath ill. Joe Slovo had recruited them. They were in South Africa to create a base for the cadres who were to attack Voortrekkerhoogte.

Getting the Grad-P into the country was challenging. It was very difficult to create hidden compartments in a Ford bakkie, into which the Grad-P could fit. The barrel of a Grad-P is 2.54 metres long. The tripod mount weighs 27.7 kilograms, and the rocket weighs between 45.8 and 46.3 kilograms.

“What was remarkable about this operation was the difficulties we had packing the weapons in,” says Aboobaker Ismail (MK name Rashid). “When I did the calculations, I didn’t count the bits that were sticking out, so every time I modelled it – and I had built little models – I was somewhat out.”

A metal frame was welded under the vehicle. The rocket launcher was mounted on a tripod under it with two rockets in the barrel, taking the weight to well over 100 kilograms.

At the border, on returning to the bakkie after processing their passports, Muller and Heath found that it just wouldn’t start. So, the distraught and nervous couple tried to push it. And the border guards very helpfully joined in! The bakkie got going again to their considerable relief. They were let through the border gates without the bakkie being checked. They waved a friendly bye-bye to the guards and went off again to ensure Voortrekkerhoogte was attacked.

“I mean, of all the things that can go wrong!’ says Rashid laughingly. ‘How many things are you meant to think of beforehand! All our meticulous planning – then this …”

Into action

Heath and Muller stocked Mooiplaas with food and other essentials for the five cadres to be based there. A few days later, Molokoane joined them. He posed as a gardener. Heath and Muller left the country.

Shortly after 20:00 on 8 August 1981, the others crossed the Swaziland border.

The cadres behaved as if they were labourers, in case anybody saw them.

Philemon Malefo, Mnisi’s friend, had a Ranchero bakkie. This was used to get the equipment to the firing point, about 4.5 kilometres from Voortrekkerhoogte. They got there at about 22:00 on 12 August.

Shortly after 22:30, Molokoane fired the first rocket, which had 43 kilograms of high explosives. There was a huge roar. People in Laudium and Erasmia came out of their houses. Most presumed it was an SADF drill and watched with interest.

With the crowd gathering, it “was like being in FNB stadium,” Mnisi told journalist Esther Waugh later.

A few people even leaned on the Ranchero as they watched. The cadres continued to fire rockets. Malefo got anxious about people being in his bakkie. He was also worried that somebody might take down the registration number and he’d be traced. So, he left in a hurry.

Evading capture

The cadres packed up the equipment quickly. But the getaway bakkie had disappeared. And roadblocks were being set up.

Mnisi went to Malefo’s place while Molokoane and the rest of the unit went back to Mooiplaas. The cadres bolted themselves

in the farmhouse, closed the windows, drew the curtains and set up their defences. They put up mattresses and moved furniture around. They took positions around the windows and waited for an attack. They were in

trouble but decided they’d fight to the death.

For three days, security forces with tracker dogs and helicopters searched the area. Sometimes the cadres could hear the murmur of voices and the barking of dogs. The search party came right to the gate of Mooiplaas but, amazingly, decided that there was no one there.

When the roadblocks eased, they left for Swaziland around 30 August. Malefo crossed at the Oshoek border legally in the Ranchero, while the others jumped over the fence and joined him on the Swaziland side. The following day, the cadres climbed over the Swaziland–Mozambique fence.

It was about three weeks after the attack that the cadres returned to Maputo. “I cannot describe the euphoria. Amazingly, everybody survived,” says Rashid. Slovo was thrilled. Oliver Tambo came to thank them for pulling the operation off.

Significance beyond material damage

“We recognised that we could not take on the SADF in a full confrontational operation,” said Rashid. “It would be suicidal – and we were never into suicide operations. We wanted the psychological impact of hitting it. That, here we are, taking on the enemy in its heart, in its biggest military base, so we left people under no illusion that we had the capability. The Boers didn’t ever, in their wildest imagination, believe that we would have struck Voortrekkerhoogte.

“On the one hand, the police are saying, look at how useless they were; they didn’t hit any significant targets. On the other hand, the people celebrated because here was the glorious MK taking on the Boers and hitting Voortrekkerhoogte right in the heart of the military machine. And what do you think the reaction was in the camps? Positive. If we’re already hitting Voortrekkerhoogte, we’re going home tomorrow – that’s how they felt. They said we’re sure the commanders will come to call us all to go to the front. And they all want to join Special Ops.

“The Boers were in a dilemma. On the one hand, they wanted to say what a big threat the ANC was, and on the other hand, they wanted to show how useless the ANC was. But now they had to deal with that question. Which is it?

“Maybe Voortrekkerhoogte portrayed MK as bigger than it was, as much more competent than we were. “

That it was attacked at all was very important. That a Grad-P was used from four and a half kilometres away added to its significance. That the cadres were able to get away safely despite a massive police search reinforced its significance.

Whatever its limits, the attack showed that the SADF was not invincible. If the physical damage was little, the psychological impact was huge. Voortrekkerhoogte, after all, was the ‘front garden’ of the Defence Force. The ANC considered the attack to be ‘a psychological landmark’, noted Waugh in an article headlined ‘Umkhonto’s cheeky blow at the military core of apartheid’.

It was the first direct attack on an army base. And it came shortly after the major Sasol and power stations operations. So, strategic sites of the apartheid regime – fuel, electricity and the military – were all hit within about fifteen months, signalling a new phase in the armed struggle.

As armed propaganda, the goal was significantly achieved. And the attack on Voortrekkerhoogte became etched in the ANC’s military history and an important part of its political capital, and it served to inspire many in the camps and outside to actively engage in the armed and broader political struggles.

* The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of IOL, Independent Media or The African.