Attack on Koeberg: How MK's Special Ops unit shattered the apartheid regime's invincibility

BOOK EXTRACT

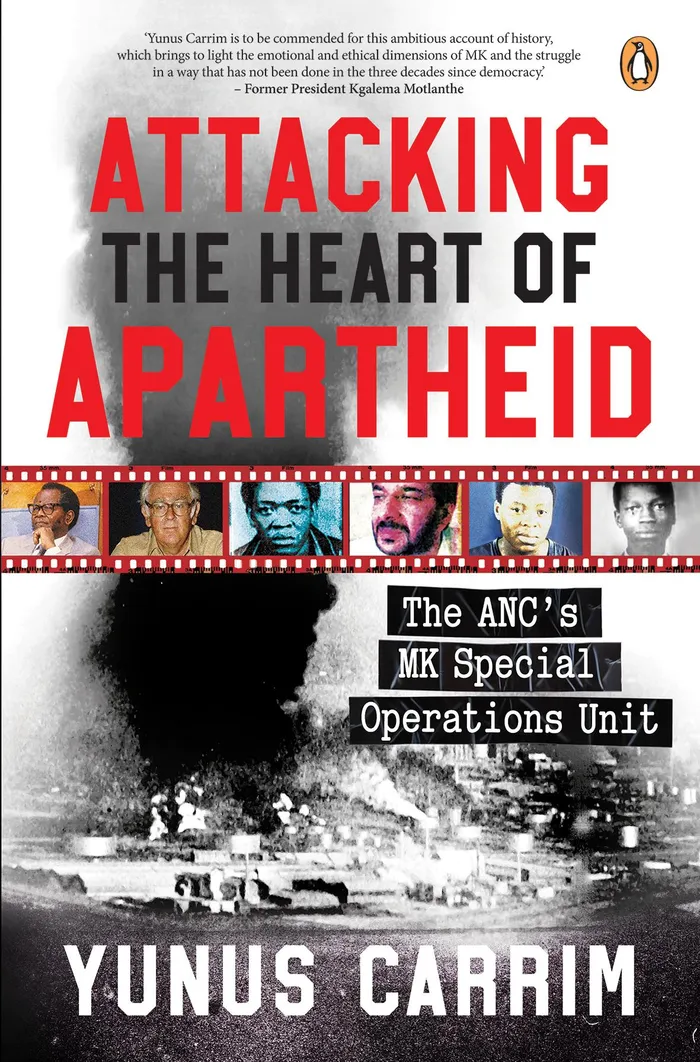

Former ANC Member of Parliament Yunus Carrim narrates the untold stories of the ANC's MK Special Operations Unit.

Image: Supplied

Blurb:

For over three decades, the remarkable story of Umkhonto we Sizwe’s Special Operations Unit has remained largely untold. Formed under the direct command of ANC president Oliver Tambo and senior ANC and SACP leader Joe Slovo, this elite unit executed some of the most daring and high-profile attacks against the apartheid state in the 1980s. In this groundbreaking book by ANC and SACP activist Yunus Carrim, the history of Special Ops is brought to life through the voices of its surviving participants. This is an account of the unit's daring attack on the Koeberg nuclear power plant.

Time was running out.

The Koeberg nuclear power station was getting ready to go online with reactor 1. So, certain areas had to be absolutely clean and free of any dust. Sections were being closed off, and the cabling conduits sealed. Security was being tightened. Rodney Wilkinson recounts:

“I was having sleepless nights about how to get a limpet mine into reactor 1. But I finally found a solution. I could get it to pass through the airlock and collect it on the other side.

“To get from the unclean to the clean area, you had to go through a change room and wear paper overalls with overshoes and a silly hat. You got searched and you weren’t allowed to take a sandwich, matchbox or anything in. If there was dust in there, you could inhale it and become a source of radiation.”

There was a tunnel from the unclean area to the clean area, with two pipes running along the wall. A panel of plywood and plastic stopped the dust from going down the tunnel. But the plywood was cut out to let the pipes through. And between the pipes, there was a gap big enough for a limpet mine. So, Wilkinson decided he would pass the limpet through that gap, go through the change room, and collect it on the other side.

With about two weeks before reactor 1 was to come online, Wilkinson had to move swiftly to get the limpets onto the site.

He took one limpet bomb at a time from their hiding place on the beach on 11, 13, 14 and 16 December 1982.

He used a screwdriver to loosen the panel underneath the Renault’s cubbyhole and put the limpets inside the dashboard. He had practised the unscrewing a lot to make sure he had sufficient time between the two security areas to get the limpets out.

“When I got through the vehicle gate, I could, while driving slowly to the office, with my gloved left hand, unscrew the dash, get the bomb into the shoulder bag, rescrew the dash panel, while driving with my right hand. And then get to the office before anybody else and lock the bag in my steel desk drawer.”

MK Special Operations operative Rodney Wilkinson narrates his unit's attack on the Koeberg Nuclear Power Station in Yunus Carrim's book titled "Attacking the heart of apartheid."

Image: Supplied

Koeberg as then was made up of two islands – the nuclear island towards the sea and the turbine island against it. The nuclear island produces highly pressurised, extremely heated steam, which the turbine island turns into electricity.

There are two control rooms. The main control room manages the reactors and the generation of power. The other control room manages the fuel and waste. Underneath the control rooms are hundreds of cables that carry out these functions.

There are two containment buildings, one for each reactor, to limit radiation leaks and contain possible explosions.

The reactor is the key component, containing the fuel and its nuclear chain reaction, along with all the nuclear waste products. It is the heat source for the power plant, just like a boiler is for a coal plant. Uranium is the dominant nuclear fuel used in nuclear reactors, and its fission reactions produce the heat within a reactor.

Wilkinson aimed to put a limpet on each of the reactors and under each of the control rooms. The fire from the explosions would spread through the cables under the control room.

To get to reactor 1, he had to go through three security checks: first, a car search at the gate, then walking past the security guard with a dog at a pedestrian gate, and then a check at the change room before entering the clean area of the nuclear island.

For the other limpets, for reactor 2 and the control rooms, he had to go through only the first two security checks.

Wilkinson’s office was between the car entrance and the two islands.

“I went with the limpets on four days through the first car gate where they could search your car, but hardly ever did,’ he says. ‘There were dogs. A mirror to stick under your car. But they just waved me on.”

He had two canvas shoulder bags. He brought the limpets in one of them, while the other, which he usually used, was left in his office drawer. He would put his work drawings in with the bomb in the bag and walk to the toilet nearby. He’d put the limpet into his belt. He had two belts so the bomb wouldn’t wobble as he walked casually through the gate, hands in his pockets, to cover the bulge, and a bag on his shoulder. The security officers would rarely check the bag.

On the 11th, he took the first limpet to reactor 1 and hid it under a big boron tank, to later put it on the reactor head.

“As reactor 1 was about to start up, I decided to use two bombs on it to make a stronger political point. But after I passed through the third security check, collected the limpet and walked towards the entrance to reactor 1, I saw this guard at the entrance, who was watching me with some suspicion. As reactor 1 was supposed to go online, there was probably no need for anybody to access it. And this guy made me so scared.

“My most tense moment. I froze and turned away from going through the entrance to reactor 1, and went back, with the limpet in the bag, as they don’t check you at the security entrance when you’re coming out of the clean area, only when you go in. I just said I’d be back in half an hour, so they didn’t sign me out.

“So, I put that second limpet in the basement under reactor 2.

“I also hid the other two bombs for the two control rooms in the basement under reactor 2.

“On the 17th, my final day at work, between 10:30 and 11:30, I took the limpets from where they were hidden and put them on the two reactor heads and the two control rooms.”

In the afternoon, he went back to the limpets, pulled out the pins, and then returned to the office. “Close to 17:00, I had a few drinks with the pallies at a farewell party, and said I was off.”

The bombs were set to go off on Saturday, the 18th, so that the likelihood of anyone being hurt would be minimal. This would be two days after the annual commemoration of the 16 December 1961 launch of MK.

Getting away

He flew to Johannesburg and put a bicycle on the plane. His sister, Cathy, and her partner, Adriaan Turgel, took him to the Swaziland border. But he couldn’t find the fence. A herd boy pointed, surprisingly, to “a silly little rusty, barbed-wire fence, looking like a farm fence, as the border crossing.

“There was a little stream a few kilometres inside. I was so relieved; it was so hot that I lay in this stream in my clothes. And it was quite a busy path, so people were laughing at me, and I was laughing too.

“The hailstorm of all hailstorms hit. So, I hid under a tree. I was so relieved, though. I felt bloody good.”

The Sunday paper reported that two bombs had gone off. “I still felt

fantastic. But I was a bit worried that the other two hadn’t gone off.”

Wilkinson flew to Maputo.

On 20 December, the news was splashed all over the world – Koeberg had been hit by four explosions! “It really was great. Nobody had been hurt, nobody got caught. It was world news.”

Slovo congratulated him and took him to meet Oliver Tambo. ‘It was like a big government house. We walked past some MK guards who greeted Joe with such affection. Tambo just hugged me, and we laughed and cried.’

Heather Gray, Wilkinson’s partner, said that:

“We had just committed a huge and highly secret act of sabotage – surely, we would be sought out by apartheid agents? It was so bloody scary. And, also, concerns about a whole new life opening for me … I think it was also the lying through my teeth to family and friends.”

The ANC arranged for them to go to the UK.

Wilkinson was keen to get involved in planning how to smuggle arms into the country. With Slovo and others, Wilkinson worked on a plan to transport arms into South Africa in a safari truck (http://youtu.be./foqURw31gmc)

Regime stunned

The Koeberg attack stunned the apartheid regime. Koeberg’s losses were about R500 million (approximately R13.5 billion today), said Eskom. The project was delayed by about eighteen months. The government was embarrassed and angered.

Some within the state wouldn’t accept that the ANC could have carried out such a slick and successful operation. Others didn’t want to publicly acknowledge this because it exposed the regime’s vulnerability. And others blamed the ANC, wanting to hit back.

An editorial in Die Transvaler noted, “From time to time we are awakened by incidents such as the Sasol and Koeberg attacks. However, it remains doubtful whether we are awake enough to remain

vigilant.”

Around 1996, Wilkinson, Gray, Aboobaker Ismail (MK Rashid), and others visited Koeberg. An engineer “congratulated us and told animated stories. He explained how frustrated they were after the first blast, not knowing how many bombs there were and others going off while they were looking for them. They were afraid they might get hurt.”

The fuses on the four limpets were set for a twenty-four-hour delay to explode on 18 December, about an hour or so apart. Despite the huge gaps between the explosions, the security services weren’t able to defuse a single limpet.

JP, the chief investigator of the bombing, refused to accept that the ANC did it, saying that they didn’t have “the skills and know-how to so accurately hit the targets.” Fourteen years later, still a denial!

A former Eskom executive, Paul Semark, claimed that they “knew the ANC would not target Koeberg once nuclear fuel was there, and they would try to attack at a time which would ensure the least loss of life. We even

pinpointed 16 December 1982, which was a public holiday, as the likely date.”

‘That’s a joke. Propaganda,’ says Wilkinson.

‘Hahaha! Oh, really!’ That was Gray’s response to Eskom’s Ian McRae’s suggestion that Baader–Meinhof (a German anarchist group) was behind it.

Plum of the establishment

Koeberg was, as Rodney says, “the plum of the establishment, it was the regime’s pride and joy, so it was a perfect place to sabotage,” notes Gray.

According to Wilkinson,

“It wasn’t visually spectacular, you couldn’t even see smoke, nothing. It was only spectacular in the news coverage. It must’ve hurt the security a lot, the feeling they’d been defeated and were vulnerable after all.”

It was also “a story of incredibly good luck”.

Rashid sees it as “A tremendous coup for us. That we could penetrate a major state institution once again showed the weakness of the regime. They didn’t have the foggiest idea of where the ANC could get to and when and how. It also showed that the ANC was everywhere.”

Most Special Ops cadres interviewed thought Sasol and Koeberg were the most effective operations.

No radioactive fallout, no casualties, and Wilkinson was out of the country before the bombs went off. The attack rattled the regime, caught the attention of the national and international media, and was an excellent example of armed propaganda. And it’s considered among MK’s best operations.

** The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of IOL, Independent Media or The African.