Emulating the 1976 generation will require resilience, innovation

YOUTH DAY

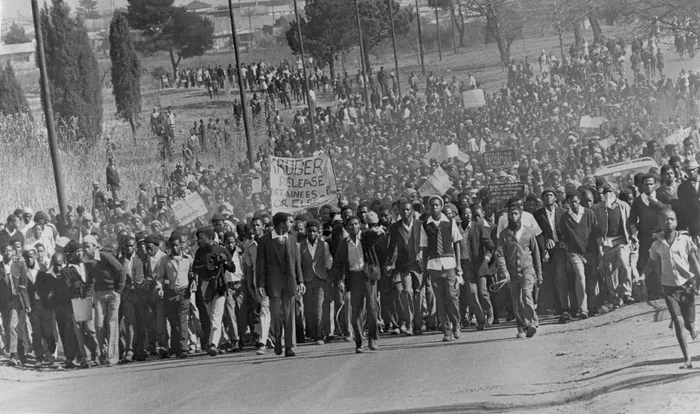

On June 16, 1976, thousands of students in Soweto took to the streets to demonstrate against Bantu Education and the imposition of Afrikaans in their schools. We owe the 1976 generation not silence, but succession. Not nostalgia, but nation-building, says the writer.

Image: Mike MIZLENI / AFP

Zamikhaya Maseti

As we mark June 16, 2025, forty-nine years since the uprising, we must ask not for the sake of ritual but for the sake of our republic: Where is the youth of today? What are they confronting? Do they carry the same fire, and crucially, do they have control over their economic destiny as the 1976 generation had over the political one?

On June 16, 1976, the youth of this land, armed with nothing but conviction and the matchbox of defiance, took to the streets and declared war against the Apartheid state. They confronted tanks with chants.

Today’s youth stand at a different frontline. It is not one patrolled by army vehicles and tear gas but by unemployment, under-skilling, digital exclusion, and economic marginalisation. The war is no longer for votes but for value. And make no mistake, it is no less urgent.

Recent QLFS data from Stats SA (Q1 2025) reveal that out of 8.2 million officially unemployed South Africans, 4.8 million youths aged 15–34 remain jobless, pushing the youth unemployment rate to 46.1 per cent, a yawning gap compared to the 32.9 per cent general rate.

Moreover, 58.7 per cent of these unemployed youths are first-time seekers, indicating acute structural unemployment and a stalling of labour market entry. The NEET rate (Not in Employment, Education or Training) stands at 45.1 per cent, signifying profound cyclical and frictional unemployment constraints.

In macroeconomic terms, this cohort’s participation inertia and underabsorption exacerbate the natural rate of unemployment and depress potential GDP growth, a symptom of underleveraged human capital and insufficient aggregate demand. This is not merely a labour market problem; it is a national emergency.

While the youth of 1976 wielded placards and songs as instruments of change, today's youth grips smartphones and Wi-Fi logins, but to what end? The digital economy, the new battlefield of production and innovation, has found them mostly on the periphery. They scroll. They consume. They swipe through innovations imported from elsewhere, yet their fingerprints are absent from the circuitry of invention. This is not participation; it is passive absorption.

There lies a pressing obligation on the Ministry of Science and Technology, indeed, on the entire State apparatus, to respond not with speeches but with strategy. The young must be repositioned from being spectators in the Fourth Industrial Revolution to being its architects.

We must ask, urgently and boldly: Where is our National Youth Tech Incubator? Where is our State-funded Digital Skills Academy, open to township youth, free at the point of use, and rich in ambition?

A well-articulated and cross-sectoral Country Youth Employment Strategy is not a luxury; it is a lifeline. This strategy must locate and activate the engines of growth where youth can insert themselves, not as interns but as innovators, not as job seekers but as job creators.

We must also interrogate the voluntaristic landscape of Youth employment interventions, particularly the much-lauded Youth Employment Service (YES), a Presidentially endorsed mechanism aimed at integrating first-time job seekers into the formal economy.

At the surface level, YES presents as a visionary model: private sector collaboration, placement targets, and experiential learning. But scratch beneath the glossy annual reports and you find a structure held up by corporate voluntarism, not sovereign will.

The State applauds from the sidelines but does not fund from the centre. There is no budget line in the National Treasury with YES's name in lights. This is the central contradiction: a government that rhetorically champions the program but refuses to place fiscal muscle behind it.

Without direct state investment, YES remains a charity model in a crisis economy, admirable, but insufficient. It cannot absorb the millions locked out of labour markets, nor can it scale against systemic constraints without an injection of public capital, regulatory certainty, and structural alignment with industrial policy. Voluntarism without velocity breeds stagnation. And the youth are tired of waiting.

Our macroeconomic data whispers a truth we must listen to: agriculture and manufacturing remain the pillars of our GDP, yet they stand like old factories, functional, but underutilised. These sectors require not only revitalisation but also infusion of young blood. In agriculture, particularly, the crisis is grave and immediate. The post-1994 public sector cohort of agricultural bureaucrats is now ageing, and with them, the institutional memory of land and food security is fading. We are sleepwalking toward a nutritional catastrophe.

Shockingly, we have 49 South African farmers, yes, forty-nine, now refugees in the United States. They are not coming back. The Minister of Land Reform must act decisively and distribute those abandoned farms, not tomorrow, not after another feasibility study, but now, as part of a radical agrarian reset. Land is not only a historical grievance; it is a living resource.

The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) is not merely a diplomatic trophy; it is an economic corridor. But who walks through its gates? If our youth do not take up the challenge of intra-African trade, someone else will. Already, the machinery of cross-border commerce is moving, but our youth remain untrained in the languages of export regulation, fintech, and customs compliance. This is where the State must intervene with scholarships, borderless internships, with youth-led export hubs.

To shape the economy, the youth must first be armed with skills. Yes, the youth of 1976 defined their destiny. They defied an oppressive order and offered themselves to history’s altar.

The youth of today must do the same, except their struggle is not to enter the political system but to redesign the economic one. They must ask themselves not “What is to be done?” but “What must we build? “June 16, 2025, must not pass like a calendar commemoration. It must sting. It must summon. It must stir our policymakers from their slumber and our Young people from their scrolls. We owe the 1976 generation not silence, but succession. Not nostalgia, but nation-building.

* Zamikhaya Maseti is a Political Economy Analyst with a Magister Philosophiae (M. PHIL) in South African Politics and Political Economy from the University of Port Elizabeth (UPE), now known as the Nelson Mandela University (NMU).

** The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of IOL, Independent Media or The African.