Celebrating Rashid Lombard: A Legacy of Humility and Courage

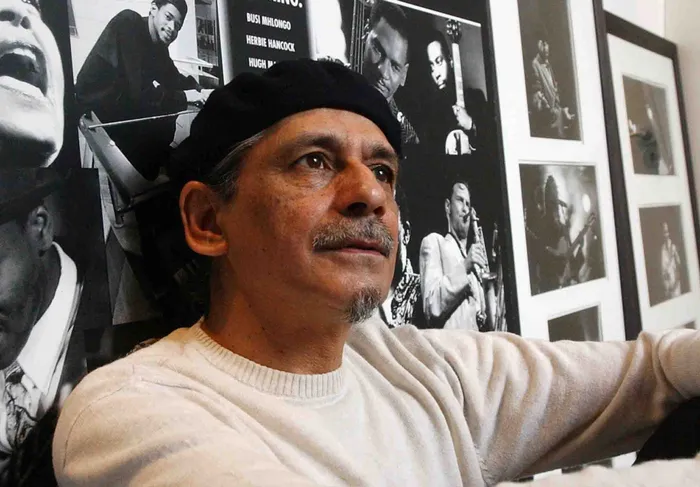

Legendary photographer and cultural activist Rashid Lombard, who passed away on Wednesday at the age of 74, surrounded by posters of iconic musicians. Rashid was a formidable news photographer and captured some excellent pictures of protests and police action during the 1980s, but his real love was taking pictures of people, especially musicians, says the writer.

Image: Brenton Geach/Independent Newspapers (Archives)

Ryland Fisher

When I was introduced more than 40 years ago to Rashid Lombard, who passed away on Wednesday, I thought his name was ‘Pusher’. Later on, I heard people calling him ‘Moena’. I never understood why he had those two names.

Such was the humility and popularity of the man that many people at the time did not even know that his name was Rashid Lombard. Not many knew that his second name was Ahmed.

Also, not many people knew that he was born in Port Elizabeth before moving to Cape Town as a young man, such has been the impact that he has made on his adoptive city over the past 40 years or more.

Even fewer people knew that Rashid was not always a lover of jazz music. In fact, in his earlier years, in the 1960s, he loved musicians such as Carlos Santana, Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin, a story related by one of his best friends, the late James Matthews, when he wrote the foreword to Rashid’s book, Jazz Rocks. “I got him to listen to Nina Simone, whose words affected him deeply, placing him in another dimension. I thought to myself, this Rashid is a cool cat. And he still is.” Matthews wrote these words in 2013 and it was true to the end.

I first met Rashid in the early 1980s on the protest-filled streets of Cape Town covering student protest actions against apartheid education, detentions and calling for the release of political leaders.

I worked part-time at first and later full-time for the Grassroots community newspaper after being employed by a newspaper belonging to the Argus Company, while Rashid worked for an overseas photographic company. Rashid became one of many photographers who provided Grassroots with photographs that their bosses would not use, but they felt should be published. The fact that Grassroots had a ‘no-byline’ policy helped these photographers hide their association with a paper that would often be banned by the apartheid regime.

Rashid was peripherally active in the Media Workers Association of South Africa (MWASA), but appeared to have found a new lease of life when a group of progressive journalists formed an organisation called the Association of Democratic Journalists (ADJ) with all of us proudly declaring ourselves ‘media terrorists’.

Rashid was a formidable news photographer and captured some excellent pictures of protests and police action during the 1980s, but his real love was taking pictures of people, especially musicians. He photographed musicians throughout the world, some of which pictures were reproduced in his book, Jazz Rocks, which was published in 2013.

Liya Williams, granddaughter of cultural activist photographer Rashid Lombard, rests her head on his coffin before his burial according to Muslim rites on Thursday June 5, 2025 in Cape Town.

Image: Ian Landsberg / Independent Media

After we became a democracy, Rashid decided to follow his first love, jazz music and worked as the first station manager at Fine Music Radio before joining P4 Radio (now Heart FM) as programme manager. He also took the audacious step in the late 1990s to bring the North Sea Jazz Festival to Cape Town and, within a few years, transformed it into the Cape Town International Jazz Festival, which is now one of the leading jazz festivals in the world.

In 2008, as the CEO of Sekunjalo Media, I led the negotiations to buy a 51 per cent stake in ESP Afrika, the company organising the jazz festival which was formed by Rashid and his partner, Billy Domingo, who also acted as production director of the jazz festival and ESP.

After Sekunjalo successfully bought into ESP, I became the chair of the company for about a year before I left to pursue other interests. It was easily my favourite job, and I learned so much about music and event planning from Rashid, Billy and Eva Domingo, Billy’s wife. I also learned much about music from Rashid’s daughter, Yana, who booked all the talent for the festival at the time.

We worked together well and very hard to turn around a company that was doing well publicly, but privately it was struggling to make a profit, which is one of the most important things for any business.

One memory that stands out for me from that time was travelling with Rashid and Billy to Mozambique to investigate the establishment of a jazz festival in Maputo. The idea was to have a series of jazz festivals throughout the sub-continent at around the same time, which would lead to economies of scale when booking foreign artists. For three days, we were hosted in Maputo by leading jazz guitarist, Jimmy Dludlu, who proudly showed off his hometown and country.

Over the years, Rashid and I would often meet, either at functions or sometimes just to catch up.

I remember how proud he was a few years ago when he announced his partnership with the University of the Western Cape to preserve his photographic archives along with that of some other photographers, such as the late George Hallet.

Rashid was a humble man and did not always know the influence he had on the lives of many people throughout South Africa. He loved music and photography (he was never without his camera), but I suspect he loved people more. He was one of those people who could never leave a party without speaking to everyone in attendance.

He loved to party and would often be one of the last to leave. I remember offering to give him and his wife a lift home from one party and then having to wait until he had said all his plentiful goodbyes.

Over the last year or so, Rashid became ill and did not venture out much. In fact, when his good friend, James Matthews, passed away in September last year, Rashid was conspicuous by his absence. But he was already very sick at the time.

Rashid married the love of his life, Colleen, in 1970 and they had three children, Chevan, Shadley and Yana. Colleen had been a trade unionist and ANC underground activists during the 1980s.

He had two other younger sons with Heidi Raizenberg, the daughter of one of his friends. Rashid returned to Colleen a few years ago after she became very ill and he undertook to look after her.

But they did not know that he too would become ill and that she would eventually outlive him.

The last time I saw him was at a gathering of struggle journalists in Kalk Bay last year where we talked about ways of intervening in the media landscape to give more voices to ordinary people.

Yesterday, his funeral was attended by a who’s who of South African politics, business and civil society. Most people arrived way before the starting time of 12h45 and only left as the sun set in the early evening.

Rashid received a simple Muslim burial, with a sendoff from his house in Burwood Road, Crawford, the coffin being carried through the streets to the mosque in nearby Taronga Road, and finally being laid to rest in the rough clay ground at the Mowbray cemetery, in the shadow of Table Mountain, before the mourners returned to the family house to wash their hands and have a meal.

The simplicity of his burial belied the greatness of the man.

* Ryland Fisher is a veteran journalist and former newspaper editor.

** The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of IOL, Independent Media or The African.