Reflecting on Black Wednesday: The Need for Caution in Media Regulation

MADLANGA COMMISSION

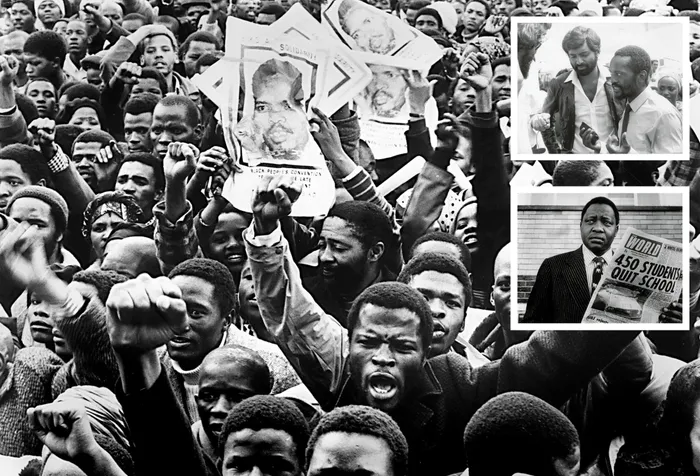

MOURNERS at the funeral of Black Consciousness (BC) leader Steve Biko in King William’s Town on September 25, 1977. INSET TOP: Then South African Students’ Organisation leaders Saths Cooper, Aubrey Mokoape and Strini Moodley were imprisoned for their BC activism. INSET BELOW: Percy Qoboza, editor of The World and Weekend World. In the aftermath of Biko's murder the apartheid regime banned 19 BC organisations, The World, The Weekend World and Qoboza was detained without trial. | Graphic: Viasen Soobramoney

Image: Independent Media Archives

Prof. Bheki Mngomezulu

On October 19, 1977, the apartheid government invoked the Internal Security Act and took two serious decisions that left an indelible mark on South Africa’s beleaguered past. Firstly, it banned two newspapers – The New World and Weekend World. It also detained some of the columnists – including the editor, Percy Qoboza.

Secondly, the apartheid government banned 19 Black Consciousness organisations. The aim was to silence the voice of anti-apartheid activists. This decision was informed by the political mood at the time, following the brutal assassination of Black Consciousness leader Steve Biko on September 12, 1977. The apartheid government was aware of the potential danger that could destabilise the country.

When South Africa transitioned to the new political dispensation, various changes were implemented to align with the new constitution. Regarding the media space, Black Wednesday was changed to National Press Freedom Day. This day is meant to honour those who fell prey to draconian laws implemented by the notorious apartheid regime. It also served as a reminder of the journey the South African media have travelled over the years to be where they are today.

Of particular importance in this regard are the provisions of the national constitution. Chapter 2, Sec 16(1) (a) and (b) states that “everyone has the right to freedom of expression.” These rights include “freedom of the press and other media,” and “freedom to receive or impact information or ideas.”

This section of the constitution was meant to undo the wrongs of the past, where the media got suffocated with their voice made inaudible. As such, journalists could not perform their duties freely. This practice inevitably deprived society of free access to quality and credible information.

Against this background, proposals made by Lit General Nhlanhla Mkhwanazi at the ongoing Madlanga Commission and the parliamentary Ad Hoc committee should be considered with sober minds devoid of any emotions. Instead, consideration of these proposals should be informed by context, the constitution, and rationality. Importantly, those who make decisions must be historically grounded so that they do not reinvent the wheel under the guise of bringing sanity to the media space and delinking journalists from politicians.

At the centre of the discussion should be a comparison or juxtaposition of then (apartheid era) and now (current political dispensation). The apartheid government was able to summarily close media outlets and ban Black Consciousness organisations for two reasons.

Firstly, the government was predominantly white and was determined to protect white interests. This meant that any media outlet that was critical of the government of the day was perceived to be an enemy of the state. Having all the powers, the state took unpalatable decisions, most of which negatively affected those who were not part of the government of the day. Among them was the state of emergency whose aim was to prevent people from gathering in numbers to plot against the state.

Secondly, the apartheid government did not want its brutality to be known by the international community. For this reason, media houses operated under very strict conditions, which made their work difficult.

From 1994, the political context changed with the advent of democracy. During this time, the interim constitution, which was adopted in 1993, annulled most of the apartheid laws and tried to bind the nation. This spirit was to be carried over to the 1996 constitution.

The inclusion of the Bill of Rights (Chapter 2) in the Constitution was an attempt to undo the wrongs of the past. Among them was to ensure that freedom of speech and freedom of association were guaranteed. Included in these rights was the freedom of the press. This was done to ensure that the media operated freely.

As mentioned earlier, changing Black Wednesday to National Press Freedom Day was part of the envisioning of a post-apartheid South Africa. This was in line with inter alia changing Sharpeville Day on March 21 to Human Rights Day, changing King Shaka’s Day to Heritage Day on September 24, and changing King Dingane’s Day to Reconciliation Day on December 16.

Given the long road that the country has travelled and given the deep wounds inflicted by the apartheid state, any decision to regulate the media should be handled cautiously. The concerns raised by General Mkhwanazi are genuine. However, these concerns should not be misconstrued to mean that the government must clamp down on the media in the same way that the apartheid government did. Any regulation should be done within the confines of the law and should not be geared towards silencing the media to avoid reinventing the wheel.

What should happen is that the weaponisation of the media by politicians should be both discouraged and condemned. This goal can be achieved in two ways.

Firstly, those in the media space should be reminded of the value of the work that they do. They should be made aware that it is in their hands to protect their profession by refraining from being used by politicians to fight their political battles.

Secondly, politicians should be told that abusing their political and financial powers to make some journalists push their political agendas tarnishes their public image, that of the journalists involved, and the image of the media fraternity. In a nutshell, politicians should be made aware that what each of them does has a direct impact on all politicians (including those who are innocent) as well as the media profession.

Lt General Mkhwanazi has good intentions for this country. He is also not against the media fraternity. His frustration in making those under whom he operates do the right thing prompted him to convene the historic media briefing on July 6, 2025. His call for the regulation of the media should be seen as curative as opposed to being punitive.

The statements and proposals made by Mkhwanazi should be seen as a clarion call for the revival of professionalism, patriotism, empathy, dedication, and focus. All these facets should be anchored on Ubuntu.

* Prof. Bheki Mngomezulu is Director of the Centre for the Advancement of Non-Racialism and Democracy at Nelson Mandela University.

** The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of IOL, Independent Media or The African.