For Morocco, a World Cup run that transcends the sport

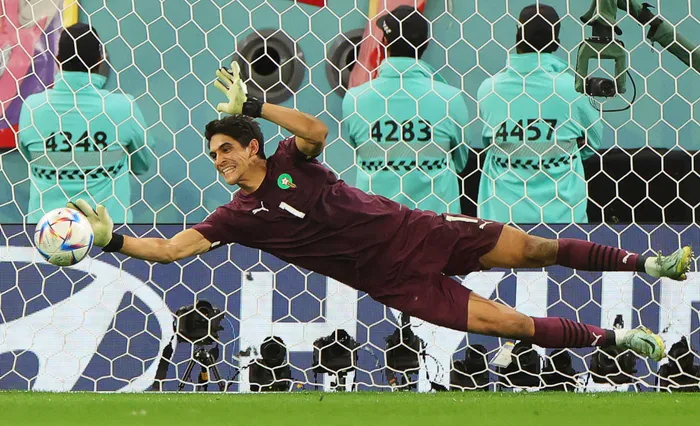

Picture: EPA/Friedemann Vogel – Goalkeeper Yassine Bounou of Morocco saves the shot from Sergio Busquets of Spain during the penalty shoot-out in the FIFA World Cup 2022 round of 16 soccer match between Morocco and Spain at Education City Stadium in Doha, Qatar, December 6, 2022.

By Graham Cornwell

This World Cup is a reminder that colonialism is hardly a distant memory. On Wednesday, Morocco will play in the World Cup semifinals. After shocking Spain and Portugal, two of its former colonisers, Morocco will face France – which ruled Morocco from 1912 to 1956. It’s a perfect anti-colonial trifecta, surely one of the most compelling narrative twists in World Cup history.

Morocco is both the first Arab and African country to make the semifinals, but it's also the seventh Mediterranean team to reach that stage of the tournament. Its Cinderella run through the tournament has been hailed across Africa, the Middle East and Europe, speaking to Morocco’s unique position in the Venn diagram of those regional identities.

European colonialism in Morocco formally ended in 1956, but the life stories of the Moroccan team embody the legacies of empire: Families who left their homeland in search of livelihoods in the lands of former colonisers, stars who never played for a Moroccan club and aren’t proficient in spoken or written Arabic but whose ties with the country never broke. To understand why this achievement – and specifically how it happened – means so much requires an understanding of Morocco’s complicated geopolitics.

In the round of 16, Morocco bested Spain on penalty kicks. As early as the 15th century, Spain began occupying strategic ports along the Moroccan coast. Then, from 1912 to 1956, Spain governed northern Morocco. To this day, Spain clings to Ceuta and Melilla, enclaves on Morocco’s Mediterranean coast. The boundaries between Morocco proper and these enclaves constitute the European Union’s only land borders with Africa.

To get to the semifinal with France, the Atlas Lions downed Portugal, 1-0. From 1415 to 1769, the Portuguese also occupied cities on the Moroccan coast. The remnants of many of their coastal fortresses still stand today.

Spanish soccer has dominated the Moroccan market for the past 20 years. There's a joke that when two Moroccan kids meet, the first question they ask each other is “Barça o Real?” – assuming a replica jersey has not given it away. Moroccan cafes often identify as either Barcelona or Real Madrid; Moroccans can play a weekly lottery guessing the results of Spain’s La Liga. What could be bigger than beating Portugal and its star, Cristiano Ronaldo – the Real Madrid legend and hero of roughly 50 percent of Moroccans – just days after ousting Spain, the country that ruled northern Morocco for half of the 20th century?

The only thing bigger is France. Compared to its North African neighbours, Morocco was under French colonial rule for a relatively short period, but those decades were transformative. Waves of Moroccans came to Europe to fight in both World Wars and to help build 20th-century Western Europe. The French had been in Morocco for just two years when they began to conscript Moroccan troops to serve on the western front in World War I.

In the years after, hundreds of thousands more followed to work in factories and farms to fill the labour gap left by the war and France’s declining population. They brought their own culture and helped weave it into the mainstream of French society. Couscous, the iconic Moroccan dish, is now a staple in French cuisine. There is no contemporary France as we know it without Moroccans and other North Africans.

The 40 years created lasting cultural, political and economic linkages in Morocco as well. Baguettes and croissants are everywhere, French is the language of the elite, and the Moroccan bureaucracy loves labyrinthine paperwork.

Millions of Moroccans have migrated to France, and generations have tried to integrate into French society while keeping a connection to the Moroccan towns and villages from where their parents and grandparents came. They’ve adopted new football clubs to support while still sporting the red of Wydad, the green of Raja or the yellow of MAS.

France’s soccer success is a reminder of the complexities of decolonisation. Just Fontaine, who set the record for goals scored in a single World Cup in 1958, was born in Marrakesh under French colonial rule. France's biggest stars of the past two decades – Kylian Mbappé, Zinedine Zidane and Karim Benzema – are of North African descent. The contradictions and complexities of colonialism go both ways.

After every game in this tournament, Moroccan Twitter and Instagram have exploded with photos of its national team's stars celebrating with their parents. Most famously, Achraf Hakimi, Morocco’s chiselled right back who usually plies his trade for Paris megaclub PSG, is greeted with kisses from his mother, a house cleaner who migrated to Madrid with her husband and raised their son and his siblings there. Sofiane Boufal, born in Paris and raised in Angers, celebrated the Portugal win by dancing with his mother on the field. The mother of Manager Walid Regragui has lived near Paris for 50 years but reportedly never travelled to see her son play or coach – until this World Cup. He climbed into the stands after the Spain win to give her a kiss.

The photos of these players and their families resonate with Moroccans because they know their story. Every Moroccan has close friends and family members in Europe. They understand the challenges of integrating into European society and raising their kids there while trying to maintain ties to culture and family back home. France and Spain formally left Morocco in 1956 but migration continued, with migrant labour essential to rebuilding the economy of Western Europe in the postwar era.

These Morocco-Europe ties create messy but powerful senses of identity. Some of Morocco’s biggest stars toyed with the prospect of playing for the European countries of their birth: Hakim Ziyech, who plays his club soccer at Chelsea, joined the youth national team of the Netherlands before switching to Morocco. Ziyech has said his mother told him, “ ‘Just listen to your heart’ – and my heart chose Morocco”. Sofyan Amrabat, Morocco’s midfield general and one of the tournament’s breakout players, also played for the Dutch as a youth but opted for Morocco as a full international.

Others on the team were born in Morocco but followed the pipeline of soccer talent as teenagers to European clubs. Youssef En-Nesyri has spent his entire professional career in Spain. He joined Malaga at 18 and moved up the ranks of La Liga to Sevilla. On Saturday, his towering header beat Portugal.

If you watch the post-match interviews, you’ll notice how many different languages the Moroccan players use. Ziyech interviews in English; Hakimi does his interviews in Spanish; Amrabat manages Dutch, Italian and English. Even those who do use Arabic occasionally get mocked in the Arab world, where the Moroccan dialect – with a heavy influence of indigenous Tamazight languages and generous amounts of French and Spanish borrowings – is notoriously difficult for Arabs from the Gulf, for example, to understand. These fluid identities are emblematic of a country that is part Middle East, Africa, Arab, Atlantic, Amazigh, Saharan and Mediterranean. In some ways, one of the legacies of colonialism was to make this identity even more fluid.

The fervour about this team in Morocco and beyond has not grown despite these contradictions but rather in embrace of them. It seems the transnational stories of these players and their families have made them quintessentially Moroccan.

Graham H Cornwell is a historian of the Middle East and North Africa based at George Washington University.

This article was first published in The Washington Post