Malawi's Democracy Falters After Flawed Elections

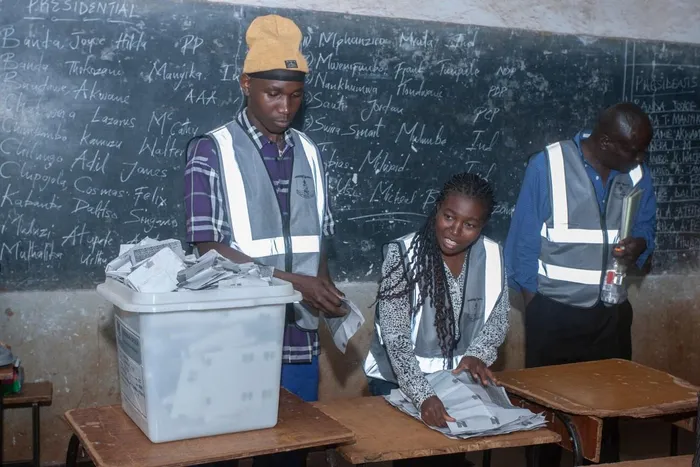

Malawi Electoral Commission (MEC) officials count votes at the end of polling for the presidential and parliamentary elections, in Lilongwe on September 16, 2025.

Image: AFP

Kim Heller

Malawi's general election took place on 16 September 2025, amid significant economic distress. For a nation where over 70% of citizens live in poverty and inflation stands at 28.2% as of August 2025, the ballot carried enormous weight. It needs to be treated with due responsibility by hopeful political candidates. Malawi’s recent electoral contest has left the country unsatisfied, and the risk of civil unrest is high.

Peter Mutharika, the 85-year-old former president of Malawi, is set to return to the power seat. Accusations of voting irregularities, premature declarations of victory, and vote tampering will nonetheless taint his victory. This latest election is sadly reminiscent of 2019, when the highest court in the land annulled the election due to a deeply compromised and flawed process.

Generally, elections are well-marketed as the foremost mechanisms of democracy. There is often a romanticisation of elections as cherished heartbeats of true democracy in practice. Elections have become synonymous with people's power, as through voting, citizens control the political compass of their nations.

This is hardly true. The ballot box can often be little more than a deceptive wishing well if the exercise of voting is compromised. Rather than offering relief, elections frequently deepen disillusionment and despair.

Grandiose campaigns, grand promises of magical reforms, impending prosperity, and anti-corruption measures are the easy speak of Presidential candidates. Too often, beneath the façade of electoral democracy, there is a lack of genuine accountability. Campaign promises rarely translate into meaningful change or structural reform.

The charming speech of the electorate typically degenerates into a pool of neglect of the citizenry once the new incumbent is in office. In the real-time of governance, rally pledges are rarely executed. Performative promises evaporate in the harsh light of reality, leaving citizens to tackle the same cycles of poverty, corruption, and exclusion that elections often fail to erase.

Elections that reproduce elite power are unlikely to effectively treat structural inequality and provide a remedy for economic recovery and prosperity.

Malawi has wrestled with political and economic instability since its independence in 1964. Thirty years of autocratic rule under Hastings Banda came to an end with the adoption of multiparty democracy in 1994, which boosted expectations for a democratic revival. However, this has not fully materialised.

The optimism surrounding President Lazarus Chakwera's 2020 victory, which promised economic recovery and an end to corruption, soon collapsed. A weakening currency, shortages of food, fuel, and electricity, and unrelenting graft eroded confidence in his administration.

Now, Mutharika's return stirs mixed emotions. His earlier presidency oversaw infrastructure investment and modest growth, but also deepened patterns of patronage. While there has been a concerted effort to portray his return as an opportunity for economic rejuvenation, the likelihood of unmet expectations is high, especially if the victory is perceived as tainted, compromised, or even illegitimate, given the deeply flawed election.

The social and economic backdrop to this election is dire. With inflation eating into wages, food insecurity spreading, and austerity measures punishing people experiencing poverty, Malawians are desperate for change.

Malawi's democratic crisis will reverberate beyond its borders. A tainted election could fuel unrest that could spill into neighbouring Mozambique, Zambia, and Tanzania. Malawi's flawed election spotlights broader issues within the region where electoral processes are becoming increasingly compromised. In many countries, the integrity of ballots is deteriorating, leading to concerns about the legitimacy of election outcomes. Weak institutions fail to uphold the rule of law, allowing for widespread manipulation and corruption.

As a result, political elites exploit these vulnerabilities to secure and consolidate their power, undermining the principles of democracy and eroding public trust in governing systems. This situation raises urgent questions about the future of democratic governance in Malawi and its neighbouring nations.

In all of this growing democratic decay, SADC is complicit. The Southern African Development Community (SADC) has praised Malawi's election for its peaceful atmosphere and high voter turnout, especially among the youth. SADC raised concerns about "isolated" incidents of intimidation but fell short of criticising the overall process.

The SADC assessment disregarded alerts from Human Rights Watch and other observer groups regarding integrity risks and potential unrest. The arrest of electoral officials for tampering confirmed these early warnings.

However, SADC's Electoral Observation Mission was quick to deliver a rather whitewashed account. SADC tends to favour stability over scrutiny, and this is a significant fault line in election assessment. While it may appease the powers that be, it undermines accountability. Shallow monitoring, lack of enforcement, and habitual rubber-stamping have turned SADC into an enabler of democratic decay rather than a guardian of regional integrity.

Malawi's 2025 election is no gold standard of democracy. Rather, it is a sad reminder that elections can entrench rather than dismantle elite dominance. When the ballot box is manipulated, when electoral commissions are compromised, and when regional bodies gloss over malpractice, democracy is reduced to a ritual without reward.

To counter this cynicism, Malawi must address all potential electoral fraud honestly. Corruption should have no standing at the ballot box. Tally sheets must be open to scrutiny and made public. Disputes must be audited appropriately, and leaders must be held accountable for any transgressions. Malawians deserve democracy, not an outlandish performance of democracy that delivers benefits for leaders rather than the citizenry.

Without transparency, meaningful reform, and responsible leadership, elections will continue to be theatrics that serve the powerful, rather than instruments of liberation for the poor.

Democracy in Malawi and everywhere needs to be constructed on the needs and unrealised dreams of citizens. Accountable governance is non-negotiable. Anything less is a vote of no confidence in democracy.

* Kim Heller is a political analyst and author of No White Lies: Black Politics and White Power in South Africa.

** The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of IOL, Independent Media or The African.