Vote-Buying Rife in Nigeria as Election Season Approaches

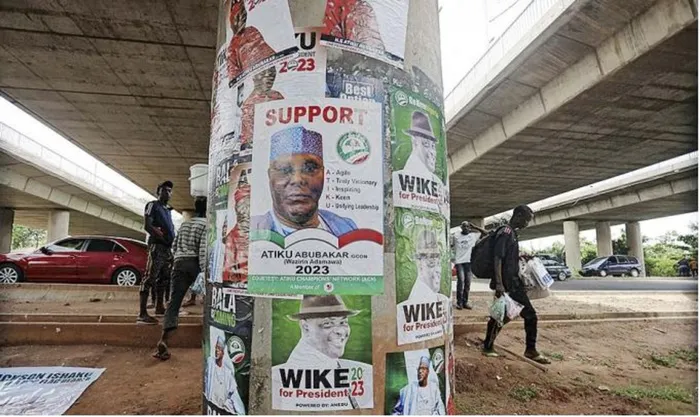

Picture: AFP – Nigeria’s 2023 presidential election is scheduled for February 25 next year to elect the president and vice president. Different banners of Nigeria’s opposition party (Peoples Democratic Party) are seen on a wall at the Central Area. The primary and gubernatorial elections has brought to the fore the reality of vote-buying in Nigeria, says the writer.

By Al Chukwuma Okoli

The 2022 primary and gubernatorial elections in Nigeria has brought to the fore the reality of vote-buying.

According to news reports, delegates to the primary elections of the two major parties were paid thousands of dollars to induce them to vote for certain candidates. In a paper published in 2017, I examined the pattern of vote-buying in Nasarawa State.

Based on my research, I concluded that vote-buying and selling had been an important determinant of electoral victory in the primary election – and that this was true of Nigeria more broadly. Vote-buying has been part of Nigeria’s electoral history, especially since the return of democracy in 1999. In the recent elections, it has assumed a more glaring dimension.

In addition, the manipulation of ballots has gradually given way to material (often financial) inducement. One factor behind the shift is the increased effectiveness of the Independent National Electoral Commission. The use of digital technology has made it more difficult to manipulate election results.

This has put electoral power back in the hands of voters, who may choose to use it as they wish. Agreeing to sell their vote – or refusing to do so – is one option. In my paper, I link the issue of vote-buying to the state of Nigeria’s democracy.

I describe it as a country in which the institutions and processes of civil rule have been hijacked by elites who are inclined to appropriate the state as their private fiefdom. This has been described as prebendal democracy, a concept developed by politics professor Richard Joseph.

It involves a self-serving elite using state power to accumulate resources, a phenomenon known as elite capture of democracy. I conclude in my paper that buying and selling is consistent with the continued materialisation and commercialisation of party politics in Nigeria.

Electioneering and partisan relations are commodified in a way that translates to economic exchange. Vote-buying compromises the quality of public leadership by putting mediocre people and rogues into power.

My analysis showed that vote-buying and selling was an important feature of electioneering in Nigeria. My research found that a good number of delegates were approached with the offer of money, with a view to inducing them into voting for a particular candidate.

Most of the delegates claimed that they collected the money without complying. But I observed that at least some must have been compromised in the process.

My findings reflect what has been known for some time in Nigeria: since the return of democracy in 1999, electoral politics has been characterised by the tendency towards monetisation.

Political entrepreneurs operate as party stalwarts and godfathers. They invest their money in party politics, with the expectation of profiteering. They capitalise on their financial stake in party structures to control who gets nominated for the various elective positions.

Once they succeed in installing their puppets into political offices, they gain unfettered access to state power, patronage and finances. This amounts to elite capture of the country’s democratic process.

There is evidence that the practice continues. In this year’s governorship elections in Ekiti and Osun states in western Nigeria, voters were wooed by party agents, with inducement offers ranging from N3,000 to N10,000 (about R410). I observed that vote-buying is the commercialisation of partisan relations between a political party or a politician and members of the electorate.

The purpose of vote-buying is to seek electoral patronage through financial or other material exchanges. Vote-buying occurs at two important stages of the electioneering process: the delegate level and the electorate level.

At the delegate level, the transaction is between a party delegate and a politician who is vying for a party ticket to run for an election. At the electorate level, it is between a voter and a political party that is seeking to win in an election. Vote-buying can be direct or indirect. Direct buying is a transaction unmediated by an agent, while indirect buying involves a thirdperson actor or an agent, who facilitates the transaction. Vote-buying can also be wholesale or retail.

It is wholesale when the intent is to buy the votes collectively. Retail buying involves individualised transactions. Sometimes votes are bought in advance. In these instances, a group of voters is handed money (or an equivalent gift) in exchange for their votes in a subsequent election.

Under these scenarios, politics is seen as an investment opportunity. Politicians and political entrepreneurs invest fortunes in party politics in the hope of reaping huge returns in terms of monetary and non-monetary rewards, such as employment and admission offers. Party delegates and the wider electorate too participate in vote-buying (as sellers).

Vote-buying thrives in Nigeria because:

* Politics is an investment.

* The premium on state power is inestimably high.

* The quest for power by the elites is desperate.

* Poverty and illiteracy make people susceptible to material inducement.

Steps should be taken to address the problems. First, privileges and perquisites associated with public office should be significantly reduced. Second, political parties should control the abusive influence of money in their candidate selection processes.

Third, the electorate should be encouraged to shun all forms of partisan inducements. Fourth, the electoral commission must ensure that the way in which polls are set up supports secret ballot voting. Vote-buying is possible and feasible in Nigeria because there are willing buyers and willing sellers, guaranteeing a reward of some kind. Until this changes, vote-buying will thrive.

In view of the negative effects on democracy, vote-buying should be discredited and stopped. Offering and taking of monetary or other material gifts by electoral actors in exchange for votes should be criminalised. And parties should turn their backs on the abusive influence of money in nominations.

Okoli is a Senior Lecturer and Consultant researcher, Department of Political Science at the Federal University of Lafia

This article was first published on www.theconversation.com

Related Topics: