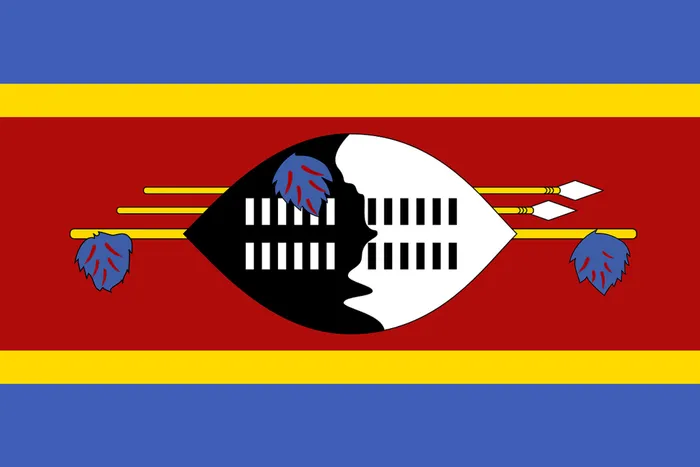

Swaziland: The sham 1968 independence

Picture: OpenClipart-Vectors/Pixabay

By Pius Vilakati

54 years! That is how long the people of Swaziland have lived under royal supremacy. That is how long the royal family has enjoyed independence while the majority of the population languished in poverty with no independence to talk about.

Over the decades, when the royal family and the government spoke about how Swaziland has enjoyed “peace and stability,” they, in fact, were speaking about how the royal family and its stooges have peacefully enjoyed the country’s wealth, a product of the blood and sweat of the people, without much disturbance. That is their “peace and stability”! Pillage and murder have been their game to ensure both gains!

The period between 20 April 1967 and 12 April 1973 may have been a period of hope for the people in so far as democratic participation is concerned, but, as history shows, the country was under the monarch’s firm control, with Sobhuza’s party, supported by white settler capital, holding 100 percent of the parliamentary seats. On paper, therefore, the country was a multiparty democracy, retaining the institution of the monarch, but in essence it was an absolute monarchy, not least because of the entire land and natural resources – and by extension the economy – vesting on the monarch.

Absolute monarchy rule in Swaziland cannot be understood without understanding capitalism as well as its history as it was imposed through the policy of colonialism. This is because the monarch as it stands today is a creation of British colonialism – indeed as many other African states.

As such, for us to draw lessons from our circumstances as well as our struggle, we need to evaluate the role of both capitalism in its imperialist stage as well as feudalism in the subjugation of the people of Swaziland.

The late 19th and early 20th centuries were important epochs in the making of the absolute monarchy. They were directly connected to the constitution-making process of the 1960s. These epochs help us understand how Sobhuza II and the royal family connived with both the British and apartheid regimes to build power around himself and the royal family while at one and the same time presenting the façade of an indigenous African “benevolent” leader who had great wishes for the people.

The late 19th century was characterised by the parcelling out of land by king Mbandzeni through concessions – some also refer to this in the SiSwati word “emakhotsiso.” These were rights given to white settlers, particularly Afrikaner farmers, for periods of about six months in a year.

After the Anglo-Boer War (1899–1902), the British emerged victorious and took effective control over Swaziland. By that time, most Swazi land had been concessioned out to the Afrikaners. Already, there were grumblings among the Swazis with regard to the land question.

The Land Proclamation Act of 1907 effectively muscled out Swazis from the land. It limited the majority, the Swazis to only one third of the land, Swazi Nation Land. Two-thirds were concessions, ostensibly capable of conversion to title deeds.

The move to buy back the land during the regency of queen Labotsibeni was premised on tightening the royal family’s control over the land. She mobilised money from the people apparently to buy back the land. This land would be under the control of the monarch though the chiefs in the communities.

At that time, the population being largely peasantry, the consciousness of the people had not reached proletarian consciousness. The royal family was thus able to strengthen its control over them. But the people’s consciousness was increasingly moving away from peasant consciousness towards proletarian consciousness as capitalism spread, but also as Swazis were pushed to assume work in the farms and mines, mainly in South Africa.

Tracing the question of British control over Swaziland, and thus how they chose the Dlamini monarchy to assume total control necessitates that we briefly trace the history of land control in Swaziland during precolonial and colonial times.

It is important to understand that when the colonialists took over Swaziland, they already found a system of production based on unequal relations to production, as Richard Levin shows in his book When the Sleeping Grass Awakens. Levin shows that in the precolonial era access to land was secured through clan membership and through allegiance ordinary clan members paid to chiefs. The control that the aristocrats and chiefs wielded over the land was transformed into a relation of production through which they maintained their dominance over their subjects.

Thus, as shown in Liciniso Issue 15: The Roots of the 2021 Uprising, the stronger clans wielded control over the land while the smaller and weaker ones had no choice but to pledge allegiance to the stronger. This is how the stronger Dlamini clan wielded its power over the rest of the clans, and at the point of colonialism it was a dominant force.

Typical of colonial regimes, the Swazi people were tossed around, from the Afrikaners to the British, all without the Swazi people’s consent. From 1884 the Afrikaners took Swaziland as a protectorate, and after the Anglo-Boer War, the British took over the land. The British had decided, without the Swazi people’s input or consent, that at a later stage they would hand Swaziland over to South Africa.

With the passage of time, particularly from 1907, the Swazi royal family understood that for them to be the most dominant indigenous grouping they had to align with British capital. To assert their dominance over the land, they decided to operate by following capitalist relations, asserting themselves as the new indigenous capitalist power while at one and the same time controlling the people in a feudalist manner.

The adaptation of foreign capital in Swaziland took various forms. These included land dispossessions, forced labour, imposition of levies by both the British colonial regime and the Swazi royal family. Thus, the road to foreign capital’s adaptation in Swaziland included collaboration between the colonising power and the local ruling class, the royal family, on the question of the exploitation of both land and labour power.

In this alliance, the indigenous ruling class had to guarantee that the people of Swaziland, males at first, would be dispatched to the mines and farms to work for British and Afrikaner capital. In return, the Dlamini dynasty became the only recognised ruling family in Swaziland despite the existence of other families with similar claims.

Consequent to this alliance with the settlers, the people of Swaziland were dispossessed of their land, forced to pay various taxes (poll tax, hut tax, dog tax, etc).

For the royal family, land provided both a material basis of power and control over the people, as well as the material basis of accumulation. Through this power, numerous monetary levies were imposed on the people (Levin).

The people of Swaziland did not take these impositions lying down, however. Their frustrations mounted, and they began to dodge their obligations. In extreme cases, people retired into hiding in the mountains to avoid royal collectors. Over time, the people began to see the royal family as an ally of the British colonialists.

By the 1940s, proletarian consciousness was rising along with Swaziland’s commercial economy premised on capitalist production. As white settler capital collaborated with the royal family, the people were pushed to the periphery, with evictions happening without compensation.

Besides the economic and political alliances between the Dlamini monarchy and the British, there were other key laws through which their alliance manifested itself. Among these were the endorsement of powers of chiefs through the Swazi Native Administration Act of 1950 in the rural areas (Swazi Nation Land). This law formed the heart of the repressive regime which facilitated forced labour, forced contributions and forced removals.

With the power that they accumulated over the years in the colonial era, the aristocracy and chiefs were well placed to engage in commodity production given their control over land allocation.

The royal family also acquired a major stake through the Colonial Development Corporation (CDC). The CDC acquired about 100,000 acres of land to set up the Usuthu Forest deal. This acquisition, as many others before, was through the eviction of the people. Foreign investment was thus contingent upon the removal, eviction and resettlement of Swazi peasant families, and this occurred with the direct participation of the royal family.

The 1963-64 workers’ strikes and wave of labour militancy which swept through all the main centres where multinational capital was located and then spread into the capital Mbabane also alarmed the British and the Swazi royal family. According to John Daniels, both the colonial state and the royal family co-operated to crush the worker challenge. Sobhuza's decisive anti-strike position impressed the foreign bourgeoisie. In this context, foreign capital came to realise that support for the traditional rulers was in the best interests of capital.

Due to the collaboration between the two forces, the Swazi royal family entered the 1960s as the single most powerful and coherent indigenous group.

The collaboration between the aristocracy and the British colonial regime continued even during the drafting of the Swaziland Independence Bill. The Bill was chiefly drafted by the British. That way, the British would still have a say in the economy of the country, particularly the land question. In the reading of the Bill, the Secretary of State for Commonwealth Affairs, Mr George Thomson, commented, “One cannot think of the economic development of Swaziland without considering the Commonwealth Development Corporation… The greatest potential for general economic development, however, still lies with agriculture.”

The drafting of the constitution, therefore, was still linked with the prospects of British control even post-independence.

When the CDC was merging Mhlume and Simunye, they also gave sweet deals to the royal family “in trust for the nation.”

One of the consequences of British and royal family collaboration was the 1968 constitution which, on the one hand, guaranteed fundamental human rights in a codified Bill of Rights, and, on the other, gave absolute control of the land to the monarchy. Before 1968, the question of the land was discussed extensively under what was known as the “Swaziland Independence Conference.” The likes of NNLC and some other indigenous political parties argued that the land and mineral resources must be returned to the people. The biggest voices, however, came from the whites who argued that the resources must be vested in the monarch.

Chapter VIII of the 1968 constitution stated that “All land which is vested in the Ngwenyama in trust for the Swazi nation shall continue so to vest subject to the provision of this constitution.” A similar clause gave the king exclusive rights to mineral resources discovered after the promulgation of the constitution. Clearly, the concept of capital resources being “held in trust for the nation” by the king was a colonial creation produced through a constitutional settlement of the national question in Swaziland.

Despite such wide powers, however, Sobhuza was still unhappy that the constitution limited his powers. He always wished to establish himself as an absolute monarch. When the British officially left Swaziland, the Dlamini dynasty had firmly entrenched its power; both political and economic. Their next allies would be the South African apartheid regime.

Tibiyo was established in 1968 by Sobhuza II following the re-investment of mineral rights to the king “in trust for the nation”. Notably, Tibiyo were given shares that they did not even pay for – as part of the British stipend to the royal family. And this culture still continues today. See, for instance, how MTN donated shares to Mswati in order to protect its monopoly.

One of the most interesting things about Tibiyo is that it was formed by a Royal Charter, not by normal Act of Parliament. This is the only time such ever happened. What this means is that parliament cannot even call upon Tibiyo to account. This is one of the reasons the Communist Party of Swaziland continues to argue that tinkhundla elections, which elect a puppet parliament, are aimed at nothing but entrenching the powers of the absolute monarch. As such, our role is to continue to mobilise the masses to boycott the elections and overthrow the regime. Those who mobilise the masses to go and queue in tinkhundla elections, so that they help Mswati to fill his puppet house called “parliament,” are helping to sustain the system. Nay more, they are part of the system!

Tibiyo embarked on a strategy of joint investment with foreign companies and the acquisition of shares in major companies. Loan arrangements with potential foreign investment partners were secured, and negotiations involving UN and Commonwealth-backed legal assistance, led to the clinching of deals in companies such as Lonrho, Turner and Newall, and Spa Holdings (Levin).

The media house, New Frame, presents one example of the power of the monarch today which emanates from British colonialism – The Vuvulane evictions story. New Frame recalls that in 1958, 10 years before Swazi independence, the British empire’s Commonwealth Development Corporation acquired the title to Farm 860 in Vuvulane, an area in the north-east of Swaziland not far from the Mozambique border. On this land, green with sugarcane fields stretching for kilometres, impoverished farmers, whose homesteads were old and crumbling, stayed in defiance of numerous eviction orders and all sorts of abuse from the Royal Swaziland Sugar Corporation. The RSSC company is owned by the king through Tibiyo.

In 1962, a settlement scheme for farmers called Vuvulane Irrigated Farms was established. The best farmers from all over the country were invited to apply for small holdings. Each would be allocated eight acres of land on which to grow sugarcane. Applicants had to be citizens of Swaziland, healthy, of good character and willing to make their home at Vuvulane. Married men with families were preferred.

By 1972, the number of established families in the area had increased to about 197 homesteads. They came from all corners of Swaziland. Upon joining the settlement scheme, farmers obtained leasehold titles to their land, with the understanding that after 20 years, ownership would revert to them.

The Vuvulane scheme was initially billed as a training mission. But people still had homes back where they came from and could not commit fully to commercial farming. The CDC thus told people to move permanently, promising to give them the land after some years, for them to own fully.

“We worked hard for this land. We knew that the English [people] would leave the land to us … And, indeed, when they were leaving, they told us that ownership of, and responsibility for, the land would fall on us now. Even the late King Sobhuza II called us and said, ‘[Vuvulane farmers], [this] is your land now. I have spoken to the English,” Mphisi Dlamini (84) who had been a Vuvulane farmer since 1963 told New Frame.

Sobhuza’s 1973 proclamation dashed all hopes of the people, especially on land and natural resources, including water, as well as prospects for self and national development. The people officially became mere subjects.

It must be remembered that the South African apartheid government fully endorsed the 1973 coup. The Swazi monarch did not pose any threat to apartheid South Africa. This is why the apartheid regime firmly supported Sobhuza’s abrogation of the independence constitution and the banning of political parties as well as the assumption of supreme power.

The ever-growing friendship between apartheid South Africa and Sobhuza led to the Pretoria Accord, signed between the two countries in February 1982. This was a secretly-signed non-aggression pact. This pact, it was claimed, bound each nation not to allow its territory to be used by guerrillas against the other. It allowed each nation to seek military assistance from the other if threatened by ''terrorism, insurgency and subversion.'' In essence, the pact meant that Swaziland would not allow the South African liberation movement to set up bases in Swaziland and that South African exiles would not find a safe haven in Swaziland. In addition, Swaziland would play a collaborative role in the illegal abduction of South African liberation fighters into South Africa, in complete violation of international law. These illegal acts were exposed in the State v Ebrahim court case [1991(2) SA 553 (A)], a locus classicus on extradition law.

Analysing the Swazi economy in 1982, John Daniels described Swaziland’s economy as an exporter of primary commodities and raw materials, a supplier of cheap labour to both the local enclaves of foreign capital as well as to an external market, and an importer of manufactured goods. One of the results of this situation included the subordination of the indigenous Swazi community to foreign capital.

It must be remembered that, apart from the pro-Western stance of the Swazi government, British and South African capital dominated certain sectors of the Swazi economy up to 1968. After independence, however, South Africa became the main economic partner of Swaziland, supplying the country with more than 95 per cent of its imports by way of a freight haulage system operated by South African Railways. The growth in the manufacturing and mercantile sectors was driven mainly by South African capital.

During the 1980s, Swaziland made financial gains from certain South African businesses that used Swazi territory as a transhipment point to circumvent international sanctions on South Africa. The royal family’s complete control over the land and politics of the country meant that it always stood at a far better advantage to trade with external forces.

Today the tinkhundla autocracy presents itself as truly African, the system as autochthonous or, put simply, homegrown. It thus relies on a great deal of phrase-mongering to appear truly African. In turn, some uncritical African commentators have clung on this fable and went on to express their support for the tinkhundla system, whether by supporting so-called Swazi “culture” as presented by Mswati’s family or other traditions. The facts of history show something different, however. The tinkhundla system is nothing but a capitalist system with feudalist elements, the royal family being a puppet of imperialism.

The system has its propagandists. This should give us lessons. For instance, historian Hlengiwe Dlamini, a relative of the royal family, attempted in her book to establish a relationship between despotism and benevolence, claiming that Sobhuza was a monarch with a “human face” and “heart”. She claims, “Although the coup gave King Sobhuza II absolute powers, he hardly abused them; he functioned more as a benevolent despot than a tyrant and blood thirsty monster, unlike some of his African contemporaries.”

This is nonsense! Sobhuza unleashed a system which has overseen the social murder of the people of Swaziland. This was in addition to the defence of the system through military means, arresting dissenters, torturing and killing them, arbitrarily evicting families without compensation, forcing many into exile, among many crimes against the people.

Sobhuza’s assumption of executive, legislative and judicial powers translated to the deepening impoverishment of the people, crimes against the people without any hope for justice in the courts. The judiciary – along with the entire court system – is firmly under the monarch’s control. The system always favours the royal family and protects its interests.

In truth, therefore, the 54 years since Swaziland’s independence from British rule has been 54 years of freedom for the royal family and 54 years of subjugation of the people. The people’s freedom is still to be realised through a revolution which must overthrow the entire institution of the monarch, replace it with a democratic republic premised on people’s power towards socialism. The new democratic Swaziland must also assert its sovereignty and be free from imperialist control, unlike the situation today.

The Communist Party of Swaziland has been running community rallies as part of grassroots-based mobilisation. The Party aims to organise the people to be their own agents of change, to not wait for a “messiah” who would come and “save” them from tinkhundla tyranny. The establishment of people’s power must begin now with the active involvement of the people in the revolution.

Vilakati is the International Secretary for the Communist Party of Swaziland