Sudan’s unending horror: What fuels the butchery?

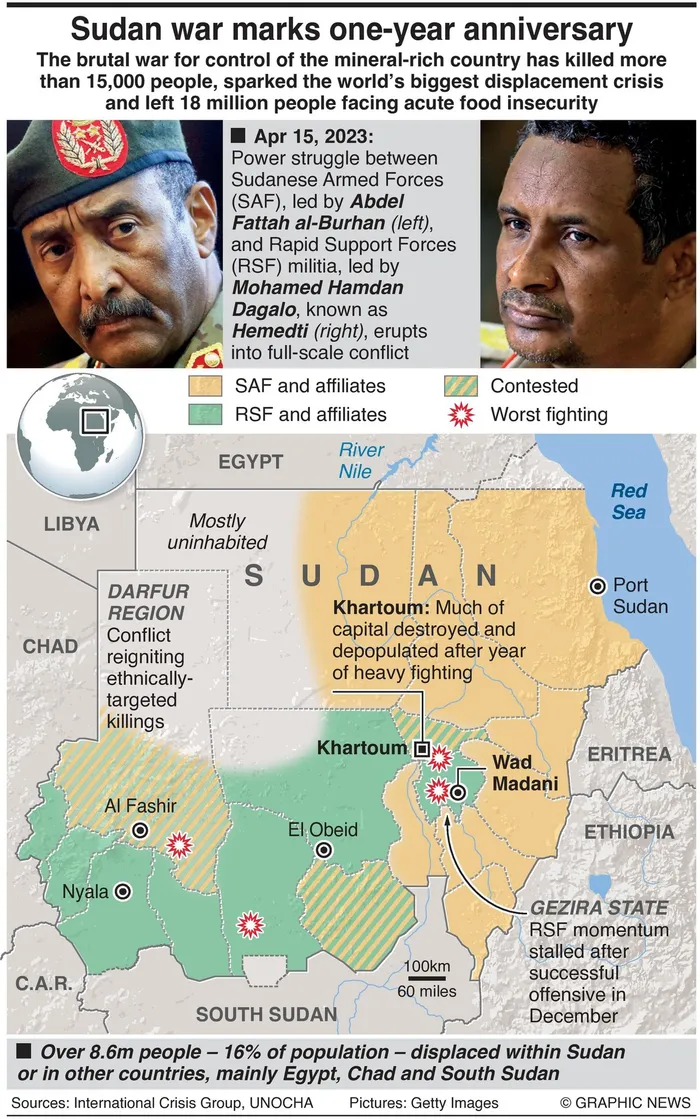

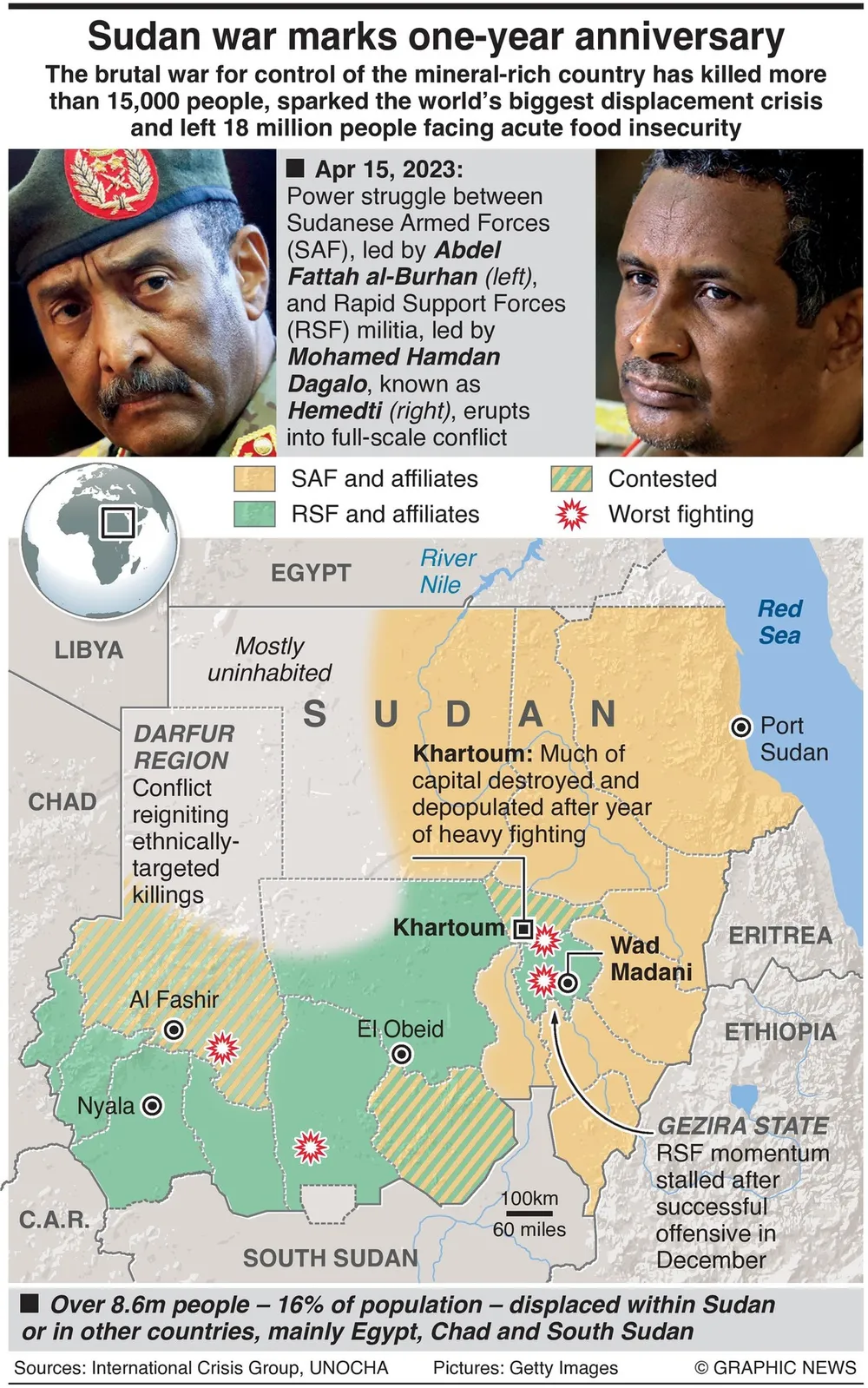

April 15, 2024 marked the one-year anniversary of the brutal war for control of the mineral-rich Sudan. The conflict has killed more than 15,000 people, sparked the world’s biggest displacement crisis and left 18 million people facing acute food insecurity. One can only hope that the true horror of a totally failed Sudan and the implications for the region and the Continent can draw parties together to propose and deliver tangible solutions, the writer says. – Image: Graphic News

A civil demonstration against the October 2021 coup in Sudan. The promise of a peaceful and democratic transition that was ‘so bright after the non-violent uprising that overthrew the long-standing military-Islamist regime of President Omar al-Bashir in April 2019, are buried in the rubble of Khartoum’, the writer says. – Picture: Osama Eid / CC BY-SA 3.0, creative commons / wikipedia

By Kim Heller

There appears to be no happy ending for Sudan. The country is on the verge of collapse as it enters its second year of civil war. With unabated wage and rage between the Sudanese Armed Forces and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces, Sudan’s population of forty-nine million people have become the wretched of the earth.

The two military groups originally collaborated to oust President Omar al-Bashir in 2019, with the intention of setting up a civilian government. However, they were to turn against each other, plunging the country into chaos and conflict.

Hopes for a peaceful transfer of power, and democratic transformation of Sudan have all but faded. According to the United Nations, Sudan is the largest displacement crisis and the biggest food crisis in the world today.

Prospects for the country, and its citizenry look bleak. The United Nations have reported that close to six million people have been displaced and that an additional 1.5 million Sudanese have fled to other countries. Over half of the population (twenty-five million people) need humanitarian aid.

This cruel era of butchery, rape, displacement, infrastructure collapse and looming famine is disfiguring the destiny of Sudan and its people.

It is a horror show. And the world has failed to stem the tragedy. The Sudanese Observatory for Human Rights has raised the alarm about the ongoing conflict in Sudan, describing it as “a war directed primarily against civilians by both parties”. The Human Rights group has warned that the human rights situation is deteriorating into catastrophe.

Earlier this year, the executive director of the World Peace Foundation, Alex de Waal, wrote how Sudan’s civil war shows no signs of ending. De Waal writes that the promise of a peaceful and democratic transition that was “so bright after the non-violent uprising that overthrew the long-standing military-Islamist regime of President Omar al-Bashir in April 2019, are buried in the rubble of Khartoum”.

If anything, Sudan’s war is likely to get worse and its impact on the region and Continent are deeply troubling. De Waal writes, “Sudan’s war is a vortex of transnational conflicts and global rivalries that threaten to set a wider region aflame.”

The highly volatile situation has forced human rights groupings and humanitarian aid organisations to retreat fully or scale down their efforts significantly. With the closure of the UN Integrated Transition Assistance Mission in Sudan (UNITAMS) earlier this year, there is now no UN entity in Sudan, leaving ordinary citizens more vulnerable than ever.

There is a need for an immediate de-escalation. Just this week, the last hospital in North Darfur was forced to close after it came under attack. The International Criminal Court’s chief prosecutor has appealed for information and evidence of atrocities in Sudan, saying his ongoing investigation “seems to disclose an organised, systematic and a profound attack on human dignity”.

Merciless, maniacal militia have not heeded the numerous calls for conflict resolution or ceasefires from various bodies, including the African Union and United Nations. The October 2023 mandate for the UN to “examine and establish the facts, circumstances, and root causes of all alleged violations of human rights, instances of abuse, and breaches of international humanitarian law” within Sudan’s ongoing conflict has not brought any relief to the people of Sudan. And despite the UN’s call for an immediate ceasefire in March 2024, fighting continues.

Multi-lateral talks have failed. The AU Peace and Security Council has not convinced the warring parties to reach consensus. To date, no intervention has been powerful enough to trigger a silencing of the guns.

Both the AU and UN appear immobilised. Avalanches of paper initiatives have proved to be ineffective ammunition against the militia in Sudan. There also appears to be a lack of intention to fully unravel the potentially menacing web of foreign interest that would benefit from the civil unrest in Sudan. Sudan’s treasured gold and prized geo-political location makes it attractive to international powers, who could well be benefitting from fuelling and maintaining conflict.

With the intense focus on Gaza, the ‘genocide’ in Sudan is not top of the agenda for the UN. Nesrine Malik, a Sudanese born journalist, wrote in the Guardian newspaper, in April 2024. “For a full year, the bodies have piled up in Sudan – and still the world looks away,” Malik writes. “And more jarring is that the world has gazed with indifference upon this crucible of war. The ‘forgotten war’ is what it’s called now, when it’s referenced in the international media.

“Little is offered by way of explanation for why it is forgotten, despite the sharpness of the humanitarian situation, the security risk of the war spreading, and the fact that it has drawn in self-interested mischievous players such as the United Arab Emirates, which is supporting the RSF, and therefore extending the duration of the war,” she writes.

One would expect that African leaders, organisations and bodies would be consumed with solving the Sudan crisis. But this is not the case. Justice bodies on the Continent have failed to take a stance. The East African Court of Justice (EACJ), which could have intervened is currently ill-equipped due to lack of funds. With the erosion of civil society groups in Sudan, the voice and role of ordinary citizens in ending the conflict is all but absent.

There needs to be a loud hailer across the world in general, and Africa in particular to end the arming of the Sudanese Armed Forces and the Rapid Support Forces. Both are being propped up by military support and weapons from foreign players, and this is emboldening them and making them less receptive to seek a peaceful or negotiated solution.

The UAE has been accused of arming the RSF, although the country has strongly denied such claims. Sudan’s army is said to be receiving aid from Iran and more recently Russia. What is certain is that there is foreign military intervention.

The Sudanese army has claimed that victory is certain. But for now, it looks like there are no winners in Sudan. When the war ends, what will be left? A broken nation, too brutalised, impoverished, and damaged to ever truly recover? A torn social fabric beyond repair?

How does one even begin to construct or even imagine a post-conflict Sudan, where girls as young as six and women as old as seventy were raped by soldiers during the warring? Will Sudan be a nation where peace and justice will never dawn?

Nesrine Malik is correct when she writes, “It’s not so much a civil war as it is a war against civilians, whose homes, livelihoods and very lives have been the collateral damage so far.” She writes that until last year, Sudan despite its conflict and dictatorship, had “managed to maintain its integrity – and with it a sense that there was a way through its troubles, after which it could achieve its potential”.

But now, hope is dying.

Cameron Hudson, a senior fellow with the Africa Programme at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies wrote that the road out of Sudan’s conflict is going to be long. He writes that “prospects for things like civilian rule and democratic elections are today more of a distraction than a serious aspiration”.

For him, the immediate focus must be on slowing the pace of war by “choking off weapons supplies” and raising humanitarian resources for increasingly desperate Sudanese. The longer-term focus is on a new transitional rule, and the slow rebuilding of Sudan.

One can only hope that the true horror of a totally failed Sudan and the implications for the region and the Continent can draw parties together to propose and deliver tangible solutions. Before it is too late.

Kim Heller is a political analyst and author of ‘No White Lies: Black Politics and White Power in South Africa’.

This article was written exclusively for The African. To republish, see terms and conditions.