Student, worker solidarity essential for nation-building

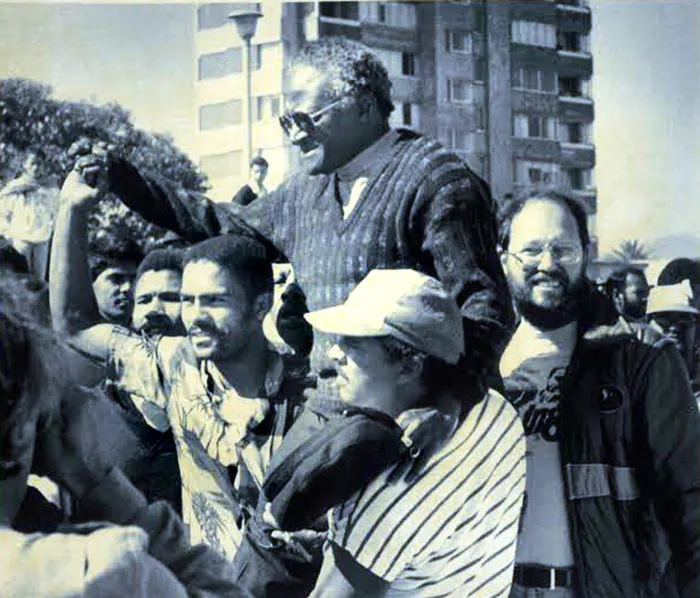

Picture: Independent Archives - The Anglican Archbishop Tutu is carried shoulder high by a group of well wishers onto the beach. the mass Democratic Movement planned an anti-apartheid beach protest thwarted by a heavy police presence in Cape Town, South Africa.

By Professor Saths Cooper

As we leave behind the most sombre, hopefully sober, reflection of our main national day – Freedom Day – last Thursday, it is appropriate to consider tomorrow’s Workers Day, which speaks to how we view and regard ourselves and our relationships at various levels of society.

There were undoubtedly shared interests and strong bonds between the small cohort of students at universities and the workers who abounded – often unseen, almost invisible – in the urban areas.

Workers – often unseen, almost invisible, if they were not white – were their parents, siblings and acquaintances, being part of the communities that they hailed from or interacted with.

These inextricable linkages gave rise to a direct understanding of their common plight, building and providing mutual solidarity. Their struggles were similar if not one. Whether it was on the choice white suburban side or the “group areas” that made up the black labour reservoirs, still labelled “townships” today if they were designated African. The white side was generally consumed with supporting with their hearts, minds and bodies their ill-gotten gains through violent colonial settlement, that eventually developed into the rabid chosen volke of Afrikaners and English.

On the black outskirts, there existed a sense of community and shared appreciation of what they confronted, despite being terrified to openly voice their opposition. Looked at more closely, it was apparent that those who were able to express their quiet resistance enabled co-operation and partnerships. Student and worker solidarity was amply evident in the university sites across the country, laying the foundations for what emerged across the various phases of mass mobilisation, even when confined to specific localities.

It was unthinkable 50 years ago for student leadership to ignore the exploitation and abuse of workers who we formed part of. This sense of being one, they are us and we are them, prevailed until about 30 years ago. The sense of community has all but evaporated, overwhelmed by the scramble for personal enrichment and immediate material advancement. Never mind who I crush, use, trick and cajole into entrusting me with their faith. Something uncanny happened. We swiftly lost our sense of looking out for one another. Many of us in strategic positions across society sold our souls to any bidder who saw in us the greed and lust for bling, glitz and all that externally makes us feel glamorous and powerful.

The toxic mix of Struggle credentials, the need for affirmation and acceptance from those who underpinned the exclusion of the majority from rightful claim to land, natural resources, the economy and a better life, gave rise to a grasping class that gave up their erstwhile roles for self-aggrandisement. What was minority entitlement grew exponentially to devour many in leadership. Whether in the student, worker, community, religious, sport, or political leadership, we gave ourselves to the demons that abased that essential dignity, self-hood and social cohesion without which no society can build for the future.

We have rendered the majority of our parents, siblings, friends, acquaintances – our fellow human beings – passive, dependent receivers of services, handouts, leering for the next prize to miraculously land on their laps.

The quest for nation-building, infusing our democracy with ingredients that bring us together, not rely on narrow alienating jurisprudence that tends to make lawyers and the wealthy continue their tight grip on society, seems to a lost cause. I look to blame everybody else for my sorry lot, even the Constitution, as if it were animate. I quickly ignore my ability to ignite the precepts that our democracy upholds, trashing the pillars that took thousands of lives to give us the start of democracy, not its end.

On Freedom Day I had the pleasure of listening to the likes of Khulekani Skosana, a new breed of youth leader, who neither denies nor defends all that’s wrong in our country, urging the majority, our youth, to regain their agency. If one does not register and vote, one cannot be part of the important change that all of us want. Relying on the sorry and motley crop who have increasingly become politicians to participate in their own personal economic empowerment, as we saw in the November 2021 local government elections, is unlikely to create the change we desire.

Individual, family, and community activism that demands actual work, doing the jobs that they are handsomely paid for, is the start. Our country is replete with all kinds of institutions that have grand offices with little visible result, cost a fortune, which are unsustainable, merely providing jobs for those who cannot deliver, while services are outsourced to providers who mostly take the money and run. No skills transfer, more dependency, less production where it matters. Skosana’s approach of accepting responsibility, instead of running away from it, is apt, and we should all play whatever meaningful roles in our little spaces that we can. Someone else is not going to do it.

Related Topics: