South Africa: End of road for apartheid’s William Nicol

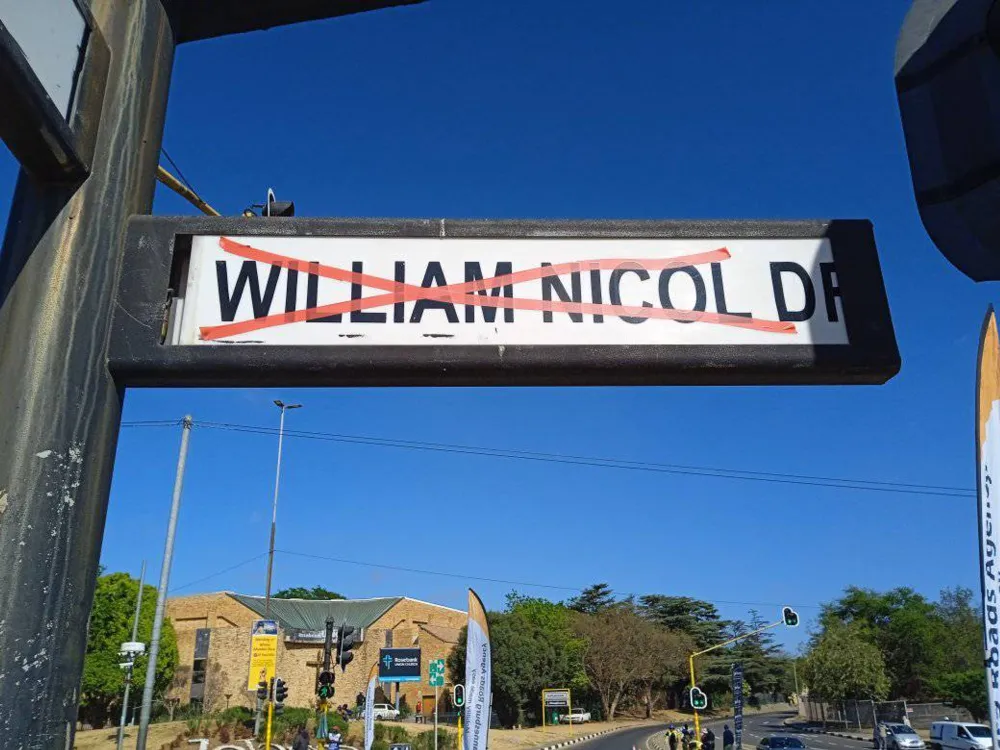

Picture: Kamogelo Moichela/IOL - Johannesburg's admired William Nicol Drive was officially renamed Winnie Mandela Drive on Tuesday morning in Sandton.

Picture: Itumeleng English/African News Agency (ANA) - William Nicol Drive has been officially renamed after the late struggle icon Winnie Madikizela-Mandela.

By Kim Heller

It is a long walk to freedom. In his final speech in Parliament in 1999, President Nelson Mandela said that giant leaps rather than small steps were required to take the nation and its people into “a bright future in a new millennium”. Mandela spoke of how there was no time to pause. “The long walk is not yet over” Mandela said, “The prize of a better life has yet to be won.”

Almost three decades later, the democratic road travelled, paved with great expectation, and large pebbles of promise, has been a long and winding path of unfulfilled possibility. In the hopscotch of Rainbow Nation politics, South Africans have become expert in sidestepping the enormous potholes of racial discrimination, dislocation, and discord. We remain more in step with grand leaps of faith than with the unsteady of large and lasting liberatory moves.

The geography of apartheid is so intact today that even the shiny new version of Google Maps and Apps cannot hide the deep gradients of racially calibrated “proudly-made-by-apartheid” geo-political spatial patterns of current day South Africa.

This week saw the end of the road for Gauteng’s William Nicol as it was officially renamed Winnie Mandela Drive, on the day that Mama Winnie, ‘the mother of the nation’ was born 86 years ago.

William Nicol was no pedestrian of apartheid. Not only was he a member of the racist National Party but of the Afrikaner nationalist Broederbond organisation. With the birth of apartheid in 1948, Nicol was to occupy the post of administrator of the Transvaal from 1948. His writings unapologetically justified racial segregation.

On Tuesday, the Executive Mayor of the City of Johannesburg, Cllr Kabelo Gwamanda, unveiled the renaming of William Nicol Drive to Winnie Mandela Drive. The renaming was a fraught three-year long process. That it took so long is a reflection of the impotence of the ruling elite.

Winnie Mandela had prophetically pointed out that the ruling party was not in power, but in office. The nostalgia and intransigence of old-world minority politicking and petitioning tried but failed to stop Winnie Mandela Drive from getting the green light.

The act of renaming streets is historically significant. The post-colonial and apartheid landscape requires progressive patriotic disruption. Replacing the street name of an apartheid devotee with that of a freedom fighter against apartheid is an important historical milestone.

Sandton Ward 90 councillor, Martin Williams speaking to a Sandton Chronicle journalist said, “It’s a waste of money, it’s a waste of resources”. He complained that the initiative was ideologically motivated, instead of practical. “Proper repairs are needed, not a name change.”

But the need to alter the geography of colonialism and apartheid cannot be discounted. Without a new decolonised consciousness and vocabulary, the fate of a democratic, free, just, and equitable South Africa will forever be impounded in the cul-de-sac of its colonial and apartheid history. The issue of potholes, poor maintenance, lack of social and economic mobility is a totally different chapter and should not be used as a subversive sub-theme to undermine or belittle this act of decolonisation.

The fall of apartheid named roads is a necessary part of a new vocabulary of decolonisation. It is as important and as symbolic as the fall of Rhodes statues, the revolutionary act by a young conscientised generation of student activists.

There has been little contestation of space in the new South Africa. Land remains in white hands, while economic power and cultural control is still a preserve of whiteness. Across the breadth of our new nation there is a flamboyant display of streets, institutions, and landmarks named after former oppressors.

The Google map of current day South Africa streets is a monopoly board of apartheid spatial and power relations. These are not respectable heritage sites but relics of racism which should have long been extracted out of the geopolitics of the new South Africa with the same force and determination that they were originally inserted.

To still have roads named after Jan van Riebeek in several of the country’s provinces is to defile the very path of a new democratic heritage and identity. Name changes such as Winnie Mandela Drive are a necessary disruption and act of decolonisation against a colonial and apartheid imposed socio-cultural landscape.

Sociologists, Saul Cohen and Nurit Kliot wrote how “naming streets and places is linked to power” Their writings focus on how place naming is part of a government’s strategy to promote specific historical events over others and, in so doing, shape national identity.

For those who find comfort and security in the architecture, language and shelter of colonialism and apartheid, it is time to say goodbye to a heritage built on acts of inhumanity against black South Africans. Of course, road name changes are not enough. Not until every inch of stolen land is returned to black South Africans.

Without land justice there will be no true geopolitical transformation and justice. But it is a start on the right path. In many ways, progressive road name changes signpost both the future and past. They make the invisible visible. They address the pandemic of black erasure and the absence of black heroes and heroines. They give due space to blackness and fill the world of black children with role models, possibilities, and pathways. Name changes are a necessary reclamation of black space, of black stories untold. It is both an appreciation of the past and an expression of confidence in the future.

Ferdinand de Jong, a Senior Lecturer in Anthropology, at the University of East Anglia wrote how “the decolonisation of heritage is a project of self-reclamation”.

The Department of Sports, Arts, Culture and Recreation regards the transformation of the naming landscape in South Africa as “a critical component of the heritage landscape as a whole.”

The Department is clear that their geographical names project is deliberately geared towards setting the country on a path towards healing “by changing names of towns and cities which have unsavoury colonial and apartheid connotations”.

In “The Power of Commemorative Street Names”, Maoz Azaryahu writes, “The main merit of commemorative street names is that they introduce an authorized version of history into ordinary settings of everyday life…Street names are more than spatial indicators, and, since the beginning of time, rulers have used spatial engineering as a form of social engineering. As a result, street names mirror a city’s social, cultural, political, and even religious values”.

Name changes are important imprints against the erasure of memory. Winnie Mandela Drive is an important story. It is one of recognition and appreciation of the of a woman whose influence was felt across the nation, whose giant sacrifices and commitment changed the path of countless men and women.

The “out with Nicol “and “in with Winnie” is part of a necessary swing against the languish and language of the past. It is part of a growing and broader “enough is enough” revolt against colonial imposition across Africa. It makes public that which was erased. Winnie Mandela Drive winds around some of the most elite, white-dominated suburbs of Gauteng. Winnie Mandela once said: “I don’t want a grand villa in a rich suburb alongside white people where many of my former comrades choose to live. I would never betray my roots in that way.”

In life, Ma Winnie was always rooted in rural black spaces and urban township areas. In death, her route will extend well beyond this. She will be omnipresent in the new South Africa.

Disrupting the easy flow of white passage, in death as she did in life. It is a healthy sign of things to come in the cityscape of decolonisation. It is a small step in the right direction.

As the African philosopher, Souleymane Bachir Diagne said, “To reclaim one’s heritage, is to reclaim one’s future”.

Kim Heller is a political analyst and author of ‘No White Lies: Black Politics and White Power in South Africa’.

This article was written exclusively for The African. To republish, see terms and conditions.

Related Topics: