South Africa: Black Consciousness leader Steve Biko's legacy betrayed

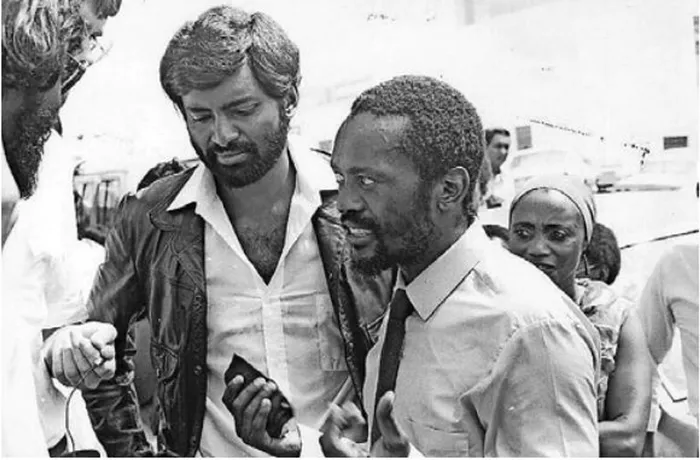

Picture: Independent Media Archives - Black Consciousness activists (from left) Strini Moodley, Saths Cooper and Aubrey Mokoape, launched the SA Students Organisation (SASO) with Steve Biko. The trio were jailed for treason as a result of their activism.

Graphic: Tim Alexander/African News Agency (ANA)/ Pictures: African News Agency (ANA) Archive, Reuters

By Saths Cooper

Tomorrow marks the 45th anniversary of the murder of Black Consciousness (BC) founder Steve Biko.

No policeman, medical practitioner, prison officer or former apartheid politician was held liable for what became an international outcry, despite the post-mortem photographs and pathology reports clearly showing gruesome evidence of torture and terminal brain damage.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), chaired by Nobel Laureate Archbishop Desmond Tutu, denied amnesty to five security policemen who appeared before it. To confound matters, successive democratic government administrations have ignored the TRC recommendation that Biko’s murder by police be investigated.

No apartheid torturer or accomplice has been brought to book for Biko’s murder, although Justice Minister Ronald Lamola has stated that specialists would be committed to investigating apartheid crimes, he and the National Prosecuting

Authority are overwhelmed by the steadily rising crime and lawlessness that has become normative, let alone grand larceny from state coffers by a slew of public office bearers. It is noteworthy that through the persistent efforts of Ahmed Timol’s nephew, Imtiaz Cajee, new inquests into the murders of Timol and Neil Aggett have found apartheid security police responsible. Steve Biko and his associate, Peter Jones (who turned 72 on Wednesday), were arrested at a security police road block on August 18, 1977 outside Grahamstown (Makhanda), on their return from Cape Town during Biko’s quest for uniting the liberation movement.

Who sold Biko out in Cape Town and elsewhere is for another time. He was kept naked and manacled at Walmer Police Station until his interrogation in room 619 at Sanlam Police Headquarters, Port Elizabeth (Gqeberha) on September 6, 1977.

This was the start of his terminal traumatic brain injury, receiving no medical treatment, instead was transferred on the back of a police vehicle to Pretoria Prison, where he died an ignominious death on September 12. On October 19, BC organisations were banned; the majority of organisations to be banned by the apartheid regime.

The June 16, 1976 student uprisings, Biko’s murder and these bannings indelibly changed the political landscape of South Africa. Over the years, commentators, writers and others have asked: “How would Biko have responded to…?” Perhaps it is appropriate to touch on the relevant question “How would Steve Biko and his generation of BC leaders have responded to SA’s leadership crisis?”

It’s important to acknowledge that many of Biko’s generation, especially since the aftermath of June 16, 1976, swelled the shrinking ranks of the older liberation organisations, especially the ANC.

Over the last few years many of those activists have narrated their experiences of reorientation, compliance with underground and training requirements, the emergence of almost complete acceptance of a harsh regimen, and the ever-present threat of being infiltrated by apartheid agents, some of whom rose to high office.

It’s also important to acknowledge that many of the founding members of the SA Students Organisation (SASO) – which in turn gave rise to the Black People’s Convention (BPC) and other student, youth and community formations – are not alive.

A very small, ageing coterie remains, and it is undeniable that some of those who were part of “Biko’s generation” and who joined the government have also been tainted by the morass that surrounds us. During the Viva Frelimo activism of September 1974, President Cyril Ramaphosa chaired the SASO branch at the University of the North (Limpopo).

The other contestant for ANC president at the last ANC Elective Conference was Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, SASO vice-president after the Viva Frelimo nationwide. At a time when we should be celebrating and consolidating our hard-won freedoms, cherishing our diversity (we’re the third most diverse country in the world), we’re confronting our most perilous and troubling period in the short history of our democracy.

Rampant racism and ethnicity, sexism, violence, poverty, hunger, unemployment and corruption appear endemic. We’re experiencing our worst period in the memory of the majority of South Africans, an unparalleled period of strife, political insecurity and economic uncertainty, of intense personal and public reflections, fractured and factionalised, when quite a few are saying we are descending into becoming a failed state.

The psyche of black South Africa, more than 28 years after the formal demise of apartheid, remains blighted by the mental subjugation of white as the aspirational standard connoting excellence, superiority and the epitome of desirability.

The subordination of black in all spheres of South African life despite our majority demographic, and the insidious resurrection of non-white as the patently inferior appellation intended to diminish, to inferiorise, to render effete and ineffectual as a coterminous appendage of white, has struck at the core of the emerging black intelligentsia, as evidenced by the nationwide student protest movement, starting with the Rhodes Must Fall campaign in March 2015, the Fees Must Fall campaign of 2016, through to popular protests against racism in sport, advertising and other spheres of our lives.

Biko’s ideas of psychological liberation as an essential precondition to physical freedom and unashamed assertion of black humanity, pride and selfhood have become as alluring today as they were when igniting youth activism and ferment in the 1970s at the height of racist oppression.

Historically, successive South African education systems aimed at creating a compliant, dependent individual, bereft of any sense of autonomy and efficacy. This is amply demonstrated by the dumbing down of our education, and its inane disabling consequences, dimming excellence and the search for solutions, creating job-seekers, destroying agency.

The quest for true humanity through the seminal ideas of Biko’s BC and cherishing our common humanity can be a base for reimagining SA and committing to go beyond narrow partisanship and sectarianism, creating a new anti-sexist, anti-violent, anti-racist platform that realises the dreams that those who sacrificed their very lives left us with. Steve Biko was the spark that ignited our open resistance to physical, mental, social and economic subjugation in the southern tip of the African continent. We have yet to:

▪ Deepen and safeguard our democratic gains.

▪ Build necessary bridges in a sea of tumultuous contestation, divisive rhetoric and intolerance.

▪ Consciously escape the marks of our origin, our historic limitations, rising above ethnicity and ideology.

▪ Work together to restore our common humanity while building a country that works and forging a nation that all of us can be proud of.

*Cooper is the President of the PanAfrican Psychology Union, a former leader of the Black Consciousness Movement, a political prisoner and a member of the 1970s group of activists.