South Africa and Namibia: Strained relations or budding romance?

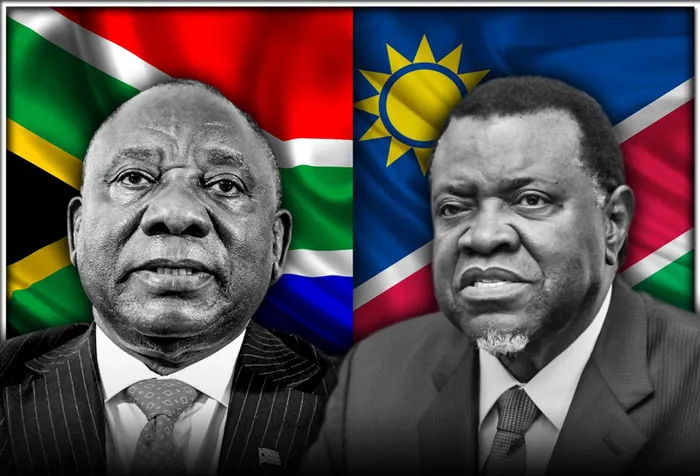

Graphic: Timothy Alexander / African News Agency (ANA) - SA President Cyril Ramaphosa and Namibian President Hage Geingob.

By Noni Mokati

Namibian President Hage Geingob arrived in South Africa on Wednesday afternoon where he was welcomed by the country's Minister of International Relations and Cooperation Dr Naledi Pandor.

The State visit is a first for Geingob since assuming office in March 2015.

It is expected that Geingob alongside his counterpart ,South African President Cyril Ramaphosa, will formulate policies that will strengthen relations between the two countries.

The two SADC-member states share a rich history which includes Namibia gaining its independence from South Africa on 21 March 1990 following the Namibian War of Independence also known as the South African Border War.

On the economic front, the United Nations Comtrade indicated that in 2022, South Africa Exports to Namibia amounted to US$3.47 Billion. The exports included vehicles, machinery, plastic, pharmaceutical products, mineral, fuels, oil and electronic equipment to name a few.

On the contrary, Namibia over the last two year exported about $988M to South Africa and last year, it exported a record number of tomatoes that were worth more than R24 million - signaling growth in its agricultural sector. Some of the other main exports by Namibia include gold, zinc, aircraft equipment, cement, lime, palstor, wood charcoal, to name a few.

Meanwhile, Geingob's visit also comes at a time where the African National Congress (ANC) and the South West Africa People's Organisation (Swapo) have had a firm political grip in the respective countries since the early 90s.

Leaders such as former Namibian President and Swapo leader Sam Nujoma alongside Nelson Mandela played an intergral role in leading the two countries to independence - independence from the Apartheid era and effectively colonialism.

For instance, in his autobiography titled: Where Others Wavered, Nujoma reflects on the fight against oppression and struggle for indipenedence that lasted 106 years first under the German colonisers and later South Africa.

He writes: "During World War I, Germany's Namibian holdings were lost to South Africa, and in 1920 the League of Nations granted South Africa mandatory powers, ostensibly to 'administer' our country and 'prepare us towards self-determination'.

He later explains that: " South African rule continued from then on through World War II, all the time increasing and intensifying the oppression and apartheid laws of the regime. In 1946 the League of Nations itself dissolved, and the United Nations assumed negotiations with South Africa to place South West Africa under the trusteeship of the UN. But the new body, dominated at the beginning by Western powers, was unwilling to apply sufficient pressure to make South Africa, their war-time ally under General Smuts, place our country under its trusteeship system. Instead, South Africa — in order to convince the international community that she had the support of the majority of the South West African people — used dirty tricks.“

“A bogus referendum was held in which the puppet chiefs, mainly from Ovamboland (whom South Africa considered to represent the majority of the population) voted on behalf of their people to incorporate South West Africa as a fifth province of the Union of South Africa. This ploy might have succeeded had it not been for the actions of Chief Tshekedi Khama of British Bechuanaland, and paramount Chief Frederick Maharero of the Hereros, who was living in exile in British Bechuanaland. They sent the Reverend Michael Scott to South West Africa to see Chief Hosea Kutako in 1947. Chief Maharero also wrote a letter warning Chief Kutako about the danger of incorporating South West Africa into the Union of South Africa as the fifth province.

“Struggles against oppressive colonial regimes continued to be intensified all over the African continent after World War II. More than thirty years after its end, the still-colonized peoples of Angola, Mozambique, Cape Verde / Guinea-Bissau and Sao Tome and Principe fought heroically to help liberate the European people of Portugal oppressed by the Salazar/Caetano dictatorial regimes."

He also admits that: "The struggles in Namibia were paralleled in neighbouring countries, where resistance also continued, unabated, to the colonial occupiers and their practices of subjugation and exploitation."

Like Mandela and Chief Albert Luthuli with the ANC, Nujoma insistend that Swapo not fumble in its quest to ensure that freedom occurs - no matter what the cost may be.

Yet, decades later, one could possibly question whether Ramaphosa and Geingob possess the same agility and mettle as the two leaders.

Ramaphosa's and Geingob's actions and their legacies will be closely monitored over the next few years, particularly in an era where the countries they lead, much like the rest of the world, have grappled with complex challenges such as the Covid-19 pandemic and economic turbulence.

Moreover, their terms in office have so far seen them dealing with a diplomatic nightmare such as the Phala Phala scandal which has raised yet-to-be-answered questions on how both countries tackled the matter.

While the tensions between Namibia and South Africa date back to time and memory, there should be no reason why these relations should be strained in 2023.

During this visit, it may be that Ramaphosa and Geingob behind closed doors need to map out a solidified strategy of dealing with issues such as Phala Phala going forward so that the "historical upheaval" that exists between the two sovereign states does not fester and haunt them for years to come.

Noni Mokati is the editor of The African

Related Topics: