Seedlings of the future central to breaking apartheid-era shackles

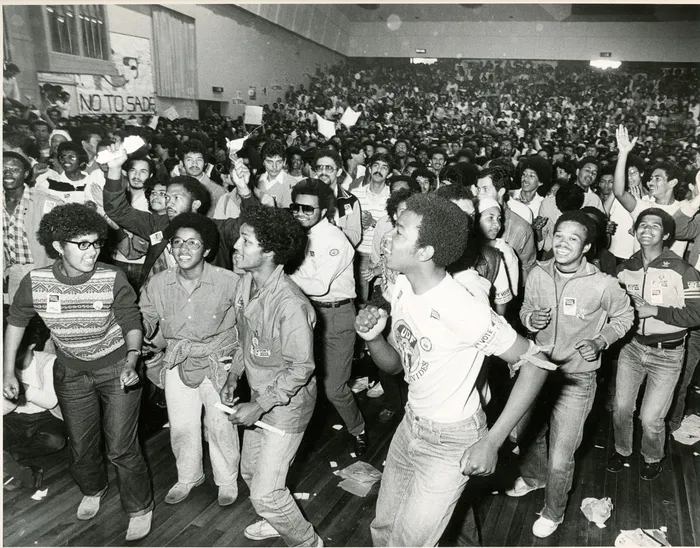

Picture: African News Agency (ANA) archive – Youth activists at a United Democratic Front (UDF) protest meeting held in Cape Town, August 1984. The UDF, like other activist movements, had some older leaders, but were ‘significantly led by younger persons’, who were socialised by the events of June 1976 in Soweto and their aftermath, says the writer.

In African Issues (Volume 22, Issue2, 1994) on Political Violence in South Africa: The Role of Youth, I wrote: “The phenomenon of adolescent marchers and activists who characterised the resistance to apartheid over the last decade has had sequelae and antecedents that reflect the core of the South African dilemma”, that “their more militant and more direct challenge to apartheid began to play an increasingly important role in the human rights struggle in South Africa.

The “older generation’s formative role in the Struggle began to diminish sharply”. The “belief that most of the older generation had somehow compromised with began to accept or diminish their ability to stand up against apartheid’s abuses”.

“So the reins of the Struggle were now in the hands of youth, who became the main anti-apartheid change agent for over twenty years from the late 1960s to early 1990. The high-water mark of this period saw Soweto and other urban black townships erupt from June 16, 1976. Steve Biko was killed, and the organisations he gave rise to were banned in October 1977.

“Another wave of youth, much larger than that flowing from Sharpeville, left the country to procure the Struggle from exile. Like the earlier post-Sharpeville wave, these youth, in the main, sought to take up arms against the apartheid system. Like the ANC Youth League before them, these youth transformed the body of the ANC and PAC in exile but not its face, which remained largely that of the earlier established, but now much older, leadership.”

This unfortunate ageing state of affairs apparently still prevails, with a few notable exceptions, such as Ronald Lamola, Panyaza Lesufi and Zizi Kodwa. I wrote that although the United Democratic Front had some older leaders, it “was significantly led by younger persons” and that their “main constituency consisted of pubescent youngsters, to youth in their early twenties, who were socialised by the Soweto events of June 1976 and their aftermath”.

I warned that “youthfulness, bereft of significant and authoritative older leadership figures exerting any direct positive and controlling influence, more exuberant political activism was displayed”.

“Risks, which may have been tempered by age, were easier to take. Greater power began to be exercised by youth, especially in punitive measures. Those who confronted one another across the barricades were youth, whether on the side of the ANC, Inkatha, Azapo, PAC, the South African Police or the South African Defence Force. Both black and white youth alike were largely from the post-1976 generation, socialised by apartheid and responding to it.

“They learned more in active involvement in the Struggle than they did in the class or at home. Indeed, especially during the mid-eighties and since, they have singularly determined the pace and form of the Struggle and held life-and-death decision-making power in their hands.

“Youth have grown up with little significant socialisation from elders to the post-1976 period. Theirs has been largely peer socialisation and being thrust into major leadership roles for which they have had poor, if little, training and developmental preparedness. Given the socio-economic deterioration and devastation that has occurred in this period, the breakdown of services, processes, structures and community and family functioning, the individual youth has had to contend with a well-nigh hopeless scenario.”

In these circumstances, rather than turn inward and inflict implosive hurt on themselves, activist youth have tended to turn outward their anger, frustration and quest for a better life. But the limitations of society restrict their choices, and the limitations of their youth restrict their expressions.

Apartheid’s intolerance has fuelled their rigid politicisation. Where apartheid brooked no questioning, many youths brook no difference in political outlook, seeking comfort in the sameness that emerges from narrow fixation. Apartheid created an obstacle out of the difference that abounds in South Africa, refusing to cherish and celebrate that difference which is essential to the human condition.

“They have come to look upon the law not as an upholder of human rights but as a destroyer, not as protector but as a persecutor, not as stabiliser and confidence-inspiring but as an unjust destabiliser and a trigger to defensive reaction.

“They have learned from the law how to respond violently, how to threaten violence as a first recourse and how to benefit from its awesome effect. All this the contrived system of apartheid has engendered in youth.

“Now that the negotiations process has taken its due course, youth have been further marginalised by that and other processes underway. From the centre stage that they enjoyed for more than 20 years, the youth now have to follow leaders, many of whom they barely acknowledge, some of whom they clearly admire but whom they are unable to really accord the full weight of the type of support that will entail curbing their excessive expressions.

“They have been denied the opportunity to really trust and engage fully, not only by apartheid but also by the resistance to apartheid. The reconciliation and reconstruction that is bruited abroad have excluded most youth, if not actually blamed them for their lot.

“A very small percentage of youth are being absorbed in the economy. A large percentage of youth have traded their education and training for leadership roles on the anti-apartheid stage. Their usefulness expended, they are being infantilised by the new compact between erstwhile oppressor and erstwhile oppressed.

“Above all else, youths who have borne the brunt of the struggle against apartheid have come to be regarded as non-essential and even dangerous to the central discussions and negotiations taking place. This marginalisation engenders more violent responses from youth who are not being accorded the understanding and affirmation that they rightfully deserve. And, in this, the old intolerant tunnel-vision continues to hold sway, constantly postponing realistically coming to grips with apartheid’s youth cohort, hoping the problem will disappear or be solved in the future!”

Twenty-nine years later, our youth, who constitute the overwhelming majority in our country, seem to confront an implacable cul-de-sac of hopelessness. Make no mistake, they want to do and be better, but all that abounds seems to thrust them into more helplessness unless it’s another protest. Then all hell can break loose, and we still wonder why.

This terrible state of affairs can be turned around. Youth can be enjoined to be part of literally repairing this damaged society, street by street, from villages to towns. Those who have held the tenders to fix things – and who patently don’t – should, as a fresh start, be required to employ youth within one month, failing which each municipality, provincial and national department should do so. In this massive visible national clean-up and repair campaign, we’ll find the seedlings for a shared future where our children can truly feel they belong.

Prof Saths Cooper is President of the Pan African Psychology Union, a former leader of the Black Consciousness Movement and a member of the 1970s group of activists