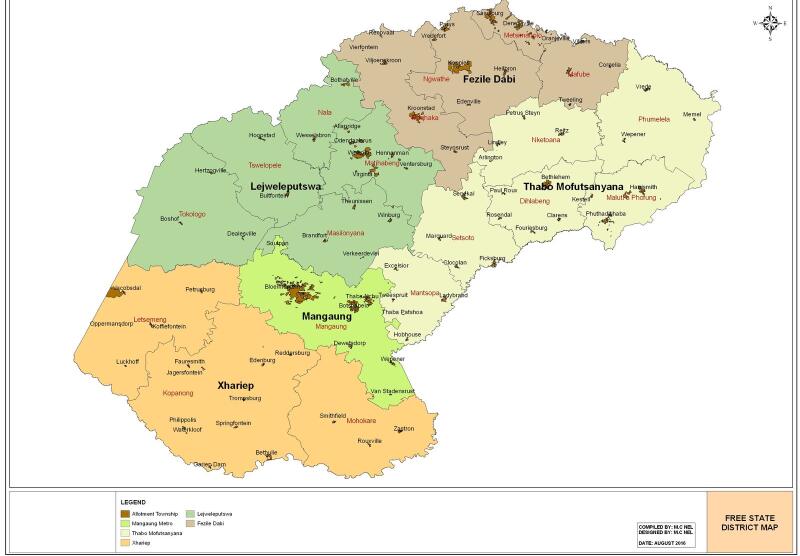

Picture: Department of Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs (Cogta) – Municipal boundaries should unite apartheid townships with economic hubs so that people live, work and shop within a single municipal area, says the writer.

By Michael Sutcliffe and Sue Bannister

Since 2000, when the first municipal demarcations were completed and local government in South Africa – as we know it today – was set up, there have been many reviews to ensure that the boundaries reflect the communities they serve, factor in changing patterns of development and movement and ensure that communities receive services equitably.

The Municipal Demarcation Board (MDB), established under Chapter 7 of the Constitution, must determine – and where necessary – redetermine municipal boundaries. In making boundary changes, the MDB needs to base their decision on the criteria provided in Sections 24 and 25 of the Municipal Demarcation Act of 1998.

There is no prioritisation of the criteria, and the board has discretion on how to interpret them. The criteria include enhancing:

- Interdependence of people, communities and economies:

This includes existing and expected patterns of human settlements and migration, employment, commuting and transport movements, spending patterns, use of amenities, recreational facilities and infrastructure and commercial and industrial linkages.

- Spatial and development planning:

This includes the need for cohesive and integrated communities, existing and expected land use, social, economic and transport planning, promotion of social and economic development, integrated development, and topographical, environmental and physical characteristics.

- Governance and functionality:

This includes provincial and municipal boundaries, democratic and accountable governance, areas of rural and traditional communities, functional boundaries, coordinated government programmes and services, effective local governance, provision of services in an equitable manner and rationalisation of municipalities.

- Financial and Administrative factors:

This includes the viability, sharing and redistribution of financial and administrative resources, inclusive tax base and administrative consequences of determination. There is a clear process for assessing redeterminations. First, the board assembles requests for municipal boundaries to be redetermined. The requests are categorised according to the spatial extent or impact of the change on boundaries.

The MDB then procures service providers to investigate, research and obtain information and assess demarcation requests. These are done in line with legislated demarcation criteria.

We were one of the service providers selected to assist the MDB in this process. As we travelled in some rural areas, we were also struck by how much had been done in bringing basic infrastructure to communities that under apartheid had none. Water, electricity and early childhood (and other) schools are now found in places that never had such services.

It was apparent that some boundaries need revision. In some cases, this was to ensure that a traditional area was not split by a municipal boundary, while in other cases, it was to ensure that economically integrated communities were brought together under a single municipality; or for more functional reasons.

Once the investigations are completed, the MDB assembles and considers the information at its disposal and decides whether to pursue a formal process for whether a boundary should be redetermined. If it decides to continue assessing the redetermination, this is known as a Section 26 process and formal requests are made for all interested and affected parties to comment on the changes.

After considering the comments from members of the public, the board may decide to undertake site visits or hold public hearings to better understand the criteria as laid down in law.

During the third step of the process, the board assesses the information received during the formal process and makes its determination (known as a Section 21 determination) on whether to change the boundary, publish the determination and invite anyone aggrieved by such a determination to submit objections or to reject the proposed re-determination.

Then the final decision of the board is published.

In the current round of redeterminations, the MDB is about to complete the first step – publishing its decisions on which of these hundreds of possible boundary redeterminations would need to be considered through a Section 26 process. The board will then, for those it decides to conduct public hearings and formal investigations, enter the process of further seeking public comment on boundary changes from all interested parties.

It is important to note that demarcation cannot solve problems in governance, service delivery and financial administration. Often commentators and stakeholders focus their attention on the issues as if all governmental problems arise from demarcation.

Poor governance can only be solved through good political and administrative leadership, and service delivery requires competent and ethical administrations.

Financial management requires management which understands and sticks to the law, ensuring balanced and realistic budgets, transparent supply chain management processes and good consequent management.

In addition, South Africa’s demarcation criteria exclude the issue of “community will” (such as whether a group of people want a boundary to be changed). This is because during apartheid, boundaries were used to divide people along race and gender lines and the continued social, racial and other divisions found in South Africa cannot be used to justify creating boundaries which will further divide them.

However, under a developmental approach to government with all three spheres working cooperatively, boundary-making is about ensuring that municipal boundaries enhance functionality and build inclusivity. Ideally, and by way of example, policing, health and education districts should align with municipal boundaries.

Municipal boundaries should unite apartheid townships with economic hubs so that people live, work and shop within a single municipal area.

It is important that boundary-making is not politicised and to “win” elections. Given that our Constitution is founded on proportionality, changing boundaries for political purposes, better known as gerrymandering, has no real effect. This is because at a municipal

level, councils are composed of councillors elected proportionally, based on the votes gained by parties.

In addition, the process of boundary-making must guard against cherry-picking – a process where communities or municipalities want to capture a “rates base” from another municipality, without properly considering the consequences. Such consequences include the potentially major disruption of services given that water treatment plants, for example, serve large areas and cannot easily have a portion divided out of their service area. Cherry-picking does also not take into account the significant need for competent and professional staff to service such new areas.

There is no doubt that over the next few months as the MDB indicates which areas will have formal public meeting processes, many of the arguments will be advanced for or against such redeterminations. Importantly, though, all those involved in such processes should assist the MDB in making sure their submissions focus on the criteria which need to be evaluated in arriving at any boundary redeterminations.

*Michael Sutcliffle and Sue Bannister are directors at City Insight (Pty) Ltd.