No need for inquiry on the failure to implement TRC proposals

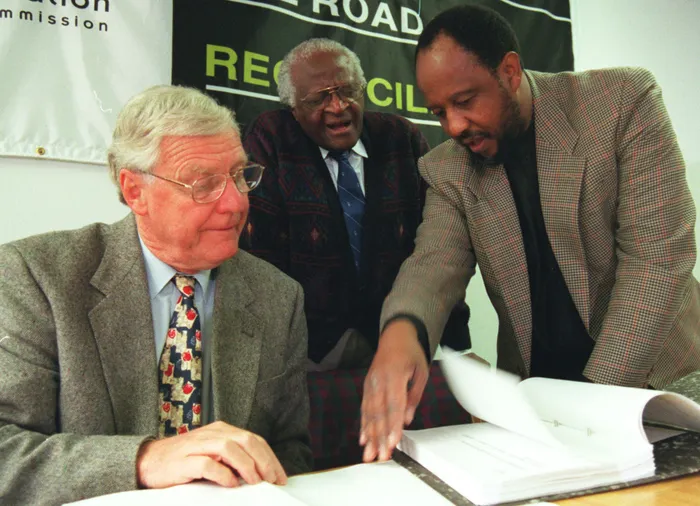

TRC commissioners Alex Boraine, left, chairperson Archbishop Desmond Tutu, centre, and Dumisa Ntsebeza. Picture: Leon Muller / African News Agency (ANA) File

By Bheki Mngomezulu

In July 1995, the Government of National Unity passed a law that authorised the formation of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). The commission was chaired by archbishop emeritus Desmond Tutu, with Alex Boraine as his deputy. The primary objective of the commission was “to help deal with what happened under apartheid”. It had to look at the plight of the victims by establishing the truth of what happened.

The period to be covered by the commission was 1960 to 1994. The decision was informed by the fact that brutality, violence and human rights violations had been carried out by the white minority who were the oppressors against the black majority. In other instances, intra-group human rights abuses happened during apartheid.

For many years, December 16 was known as Dingane’s Day, following the Battle of Blood River (Impi yase Ncome) between Zulu King Dingane and the Voortrekkers.

The Voortrekkers emerged victorious and thus celebrated this day. It was also on the same date that Umkhonto weSizwe (the military wing of the ANC) was established.

Given the historical significance of the date, it was decided that the first sitting of the TRC would be on the same date. Addressing the gathering in his capacity as chairperson, Tutu described the holiday as a symbol marking the beginning of an attempt to heal the wounds that had been inflicted by the apartheid regime. It was for this reason that the holiday became known as Reconciliation Day on the South African calendar.

Initially, the TRC was scheduled to sit from 1995 to 1998. However, its life was extended until 2002.

The extension was occasioned by the fact that the process turned out to be more complex than initially anticipated. Moreover, there were more cases to be heard than previously thought. There were also instances when the sitting had to be postponed for one reason or the other. Given the circumstances, prolonging life of the commission was justifiable.

After concluding its work, the TRC compiled its multivolume report in which it made several recommendations that had to be implemented by various state institutions.

However, the commission had no mandate to oversee the implementation of its recommendations. This meant that the power resided elsewhere. Various government institutions had to take over from where the commission had left off.

One of the accusations levelled against the TRC is that it failed to address social and economic transformation as anticipated at its inception. Part of the reason is that the country had resolved to embrace reconciliation as opposed to firmly punishing the perpetrators of the atrocities that were laid bare during the hearings.

The only incentive for coming forward with the truth was that the perpetrator who divulged the truth would be pardoned for their crimes. Not everyone grabbed the golden opportunity. Consequently, many questions remain unanswered.

The National Prosecuting Authority (NPA) failed to move with speed in conducting investigations and bringing to book all those who were implicated at the TRC. This meant that many questions were left unanswered. Various reasons have been provided for the NPA’s failure to deliver on its mandate. One of them is a lack of resources – human and financial.

To this day, some families are yet to know what happened to their loved ones. Even the financial support recommended by the commission did not reach all the intended beneficiaries. This is so because the commissioners were given the power to grant amnesty to those who divulged the truth about what happened during the period in question, thereby earning amnesty, but it was not given the power to implement its recommended reparations.

It is within this broader context that advocate Dumisa Ntsebeza SC has proposed that an independent inquiry must be carried out to investigate the possibility of political interference in the delayed implementation of the recommendations of the TRC.

As someone who was involved in the process, he is frustrated by the pace at which the process has either unfolded or stalled.

While the concerns are understandable, I hold a different view.

There is no need for an inquiry into potential political influence in the delayed implementation of TRC recommendations, for several reasons.

First, the country’s economy is not doing well. Any money allocated for an inquiry into the possible political interference in the TRC cases would be a waste.

Second, many inquiries have been conducted but little or no change has happened after that. Undertaking another inquiry when previous ones have not produced positive results would not make sense.

Third, on March 5, the NPA released a statement indicating that the current leadership has resolved to prioritise justice in the TRC cases. According to the statement, of the 137 cases registered, 21 have been finalised while 10 matters are on the court roll.

Establishing the reasons for the slow pace in concluding the matters does not need an inquiry.

Fourth, Ntsebeza has been appointed to review the measures adopted by the NPA to deal with and prosecute TRC matters and to make recommendations. The onus is on him to move with speed while doing due diligence on the task at hand.

Last, with 2024 marking 30 years into democracy, there is more urgency to conclude TRC matters, not to conduct another inquiry.

Prof Bheki Mngomezulu is director of the Centre for the Advancement of Non-Racialism and Democracy (CANRAD) at the Nelson Mandela University