No Feast of Democracy in Egypt

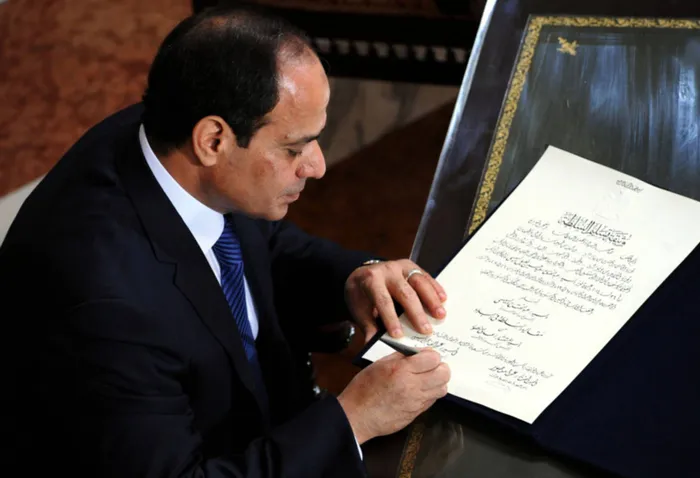

Egyptian President Abdel Fatah el-Sisi signs a handover of power document, transferring the presidency to him from interim President Adly Mansour in the presence of dozens of local and foreign dignitaries at the presidential palace in Cairo. Sisi was inaugurated as President on June 8, 2014.

Egyptian protesters run as they clash with riot police at Cairo's landmark Tahrir Square on November 19, 2011. Egyptian police fired rubber bullets and tear gas to break up a sit-in during the Arab Spring, which resulted in the overthrow of then president Hosni Mubarak. But President Abdel Fattah El-Sisi, who overthrew the democratically elected president Mohammed Morsi in a coup has dampened this political spirit of the people, the writer says. – Picture: Khaled Desouki / AFP

By Kim Heller

“Down with dictators!” Down with corruption!” On January 25, 2011, the Tahrir Square, in Cairo, was a scene of massive protests as Egyptians took to the streets to demand the resignation of President Hosni Mubarak. It was a time of fury.

The people of Egypt had become increasingly disgruntled as government corruption, political repression and autocracy slowly but surely become the hallmarks of Mubarak’s thirty-year long reign. A deathly tonic of poverty, high living costs, poor economic prospects and growing unemployment led to a toxic brew of anger that was to spill across the streets and squares of Eqypt.

Eighteen days of unrelenting protest, which saw over eight hundred people killed, and thousands more injured, left an indelible mark on the nation. The fate and fortune of longstanding President Hosni Mubarak was decided on the will of the people. He was to fall from power, along with his vice president. A year later, Egypt held its first ever Presidential election. The Muslim Brotherhood’s Mohammed Morsi took office in 2012.

It was a time of hope.

During his acceptance speech on 24 June 2012, the new President, Mohammed Morsi, spoke of how the people of Egypt were celebrating the “feast of democracy in Egypt” after decades of being subjected to hunger, injustice, and oppression.

But there was no democratic feast for Egyptians. Morsi served as the country’s President for just over a year before he was toppled in a military coup, spearheaded by General Abdel Fattah El-Sisi. Morsi was to spend his last days imprisoned, in solitary confinement. He took his last breath on June 17, 2019.

Abdel Fattah El-Sisi Eqypt was sworn in as the new President of Egypt in June 2014. Under President El-Sisi, the economy has all but collapsed. There have been massive waves of political suppression and sweeping human rights violations.

Hossam el-Hamalawy, an Egyptian journalist and socialist activist wrote in 2023 about waves upon waves of state terror and the seemingly permanent authoritative rule. Laws have been passed to paralyse the country’s once vibrant NGOs and many political opponents and human right activists have been attacked and jailed. Under the President’s idiom of stability and security, dissenting voices have been squashed or entirely snuffed out, and the military continues to hold control over critical economic assets and a stronghold over civil society.

Grand promises of prosperity and development have yet to manifest. Ever-rising inflation and debt burdens, coupled with a serious shortage of foreign currency, has plunged the country into an economic abyss. In September 2023, Bloomberg cited Egypt as the second most vulnerable country to a debt crisis after Ukraine.

In 2023, Amr Magdi, a senior Middle East, and North Africa researcher at Human Rights Watch (HRW), wrote of the protracted economic and financial crisis as a self-perpetuating cycle of failure by the El-Sisi government. But the President has held onto power.

A 2019 constitutional amendment enabled El-Sisi to stand for a third term. Presidential elections were held in a rushed fashion in December 2023. Over 39 million Egyptians cast their ballots for El-Sisi (89 percent of the electorate). While the high turnout and landslide victory may, at face value, be seen as a firm marker of support for the incumbent President, the electorate had few presidential choices.

The Human Rights Watch (HRW) 2024 World Report claims that free expression and peaceful assembly were severely hampered in the period leading up to the December presidential vote. This included politically motivated arrests, arbitrary detentions, intolerance of peaceful protests, and unfair trials of journalists and activists.

While El-Sisi emerged victorious, this may not be a win for ordinary, increasingly economically fatigued, and desperate Egyptians. The economy is fragile. HRW’s Amr Magdi, wrote, “No amount of repression can hide the fact that Sisi’s government has failed to protect if not actively worsened the economic, civil, political, and social rights of Egyptians.”

During his first two terms in office, El-Sisi focussed, almost obsessively, on extensive infrastructure development. Whilst infrastructure has been improved and expanded, especially the travel and transport infrastructure, this has yet to boost economic growth or expand employment opportunities. The heart of the infrastructure spend has been on the construction of a new $58 billion capital in the desert, east of Cairo. While El-Sisi claims that this development “would mark the birth of a new republic” there has been a score of criticism of this ‘smart city’ in a country that is economically spent and in debt of more than US$100 billion.

As he begins his third term in office, El-Sisi has promised economic reform based on the localisation of industry, expansion of agriculture, increase of direct foreign investments, and support for the private sector. He has also promised necessary social protection measures for the most vulnerable, and has pledged to prioritise good education, and decent health services and housing. However, during his time in office he has cut subsidies to the poorest sectors of the population.

2024 got off to a good start for the Egyptian economy. In early 2024, Eqypt received a well needed investment injection. A US$35-billion land development deal with the United Arab Emirates and a strong bonanza of loans and financing agreements from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), World Bank (WB) and European Union (EU) places Egypt in a far better position than it has been for many years. But the year ahead is likely to be trying for Egypt.

For now, democracy is a feast that the people of Egypt have yet to enjoy. Internally, economic battles wage on as the majority of the 106 million citizens struggle to keep up with rising living costs, and fight against ever-lingering poverty. The economy remains weak with inflation above 30 percent.

Externally, Egypt is vulnerable as two serious human catastrophes in Sudan and Palestine play out along its borders. Desperate refugees are seeking shelter in Egypt. This places Egypt in a vulnerable economic and security quandary.

In his opinion piece, published by the German based Rosa Luxemburg Foundation, earlier this year, Hossam el-Hamalawy wrote that “the war between Israel and Hamas has exacerbated the country’s political and financial woes”. He points to how the Houthi attacks in the Red Sea have resulted in significant income dips in shipping transit income for Egypt.

The Israel- Palestine conflict is also exposing the declining legitimacy of an El-Sisi-led Egypt, both within the country and in the region. Egypt’s role as mediator between Palestine and Israel has become less influential. While Egypt has long portrayed itself as a peacemaker in the region, its limited interventions have been largely ineffective. Rather El-Sisi appears to be using these regional conflicts to mask Egypt’s own domestic crisis and shift attention away from its dire state.

Professor Mohammad Fadel, a legal and economic expert, argues that El-Sisi and his allies have destroyed politics in Egypt. He writes, “Egyptian civil society has never been so thoroughly decimated and demoralized. Even in the darkest days of Hosni Mubarak's rule, a public culture of criticism and intellectual ferment existed. There was a modicum of hope that the Mubarak regime could be persuaded to increase space for democratic participation and accountability. Even though that space was relatively small, it was enough to allow for the possibility of politics and for Egyptians to dream of a better future through collective democratic action.”

El-Sisi may have built an elaborate bright new administrative capital, but he has failed to deliver the basics; a democratic, thriving, and prosperous nation. For now, it is more feast than famine of democracy in Europe. It is symbolic that the revolutionary Tahrir Square, has been revamped and modernised. It is as if the very site of the struggle has been expunged. But a people’s fury cannot be so easily erased.

The third term of El-Sisi may be turbulent if he is unable to address the real and legitimate socio-economic challenges of the people of Egypt. Repressing dissenting voices is not a viable long-term political strategy. In the end, the people will rise. Again. And it will be a time of fury.

Kim Heller is a political analyst and author of ‘No White Lies: Black Politics and White Power in South Africa’.

This article was written exclusively for The African. To republish, see terms and conditions.