Niger: The legacies of colonialism and the US War on Terror in West Africa

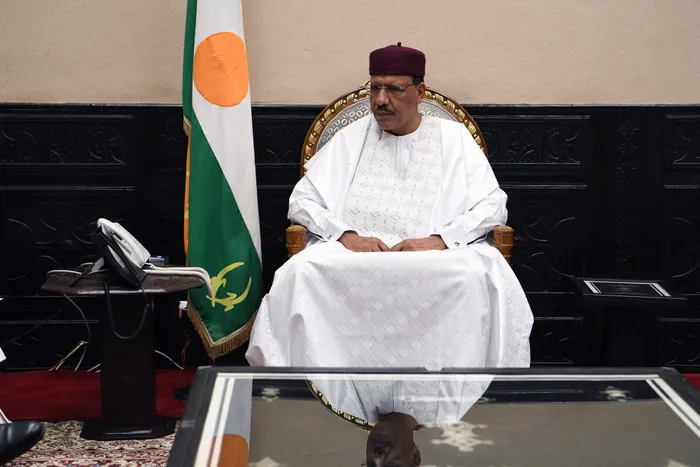

Picture: Bertrand Guay / AFP / Taken on July 15, 2022 – Nigerien President Mohamed Bazoum meets with the French Foreign and Armies ministers during their official visit to Niamey on July 15, 2022. While the coup in Niger can be seen as a response to the deep-rooted issues of corruption, inequality and governance that have plagued the country since independence, the heavy reliance on security forces [instead of peoples organisations to lead change] has allowed military leaders to consolidate power and exploit the rampant vulnerabilities within the political system, the writer says.

By Christopher Zambakari

A closer examination of conflict connections and motivations reveals hidden agendas, geopolitical strategic moves, and the struggle for control in Niger.

Introduction

Niger is nearly 500,000 square miles of landlocked country bordered by no less than seven neighbouring states. It is a country saddled with a history of military interventions. However, most recently, under the leadership of President Mohamed Bazoum, it has been regarded as a ‘model of stability’ and ‘model of democracy’ in a region marred by political instability. Bazoum’s election in 2021 and the subsequent peaceful transition of power raised expectations of democratic rule and a renewed commitment to good governance. However, the military coup shattered those prospects and exposed the fragility of democracy in West Africa.

In the current political upheaval, the key players include not just the domestic military forces, but also international powers. A legacy of French colonialism and the US Global War on Terror looms large over the region, casting its shadow on a complex narrative. However, the militarised ambitions of both regional and global actors prevail in West Africa and Niger again is caught in the crosshairs.

As one considers the nuances of the situation, two compelling questions emerge: How has the militarisation of West Africa, explored through the lens of the War on Terror, set the stage for the recent coup in Niger, and what does this upheaval signify for the future of the region? Amidst the shifts in power, a closer examination of conflict connections and motivations reveals hidden agendas, geopolitical strategic moves, and the struggle for control in Niger.

This coup is different

The coup began in late July 2023 and unfolded differently from the typical trajectory of political upheavals in West Africa. On July 28, 2023, the head of Niger’s presidential guard, General Abdourahamane Tchiani, declared himself head of state after the military seized power. While General Tchiani justified the overthrow with the troubling security and economic issues,there have been suggestions that he acted upon hearing reports that he was about to be removed from his position.

The international response to the Niger overthrow was swift and resolute. The US and France, key allies in the fight against terrorism in the region, threatened to sever ties with Niger and suspend military cooperation. The European Union (EU) and the United Nations (UN) condemned the action. Closer to home, the Economic Community of West African States (Ecowas) threatened to send troops if Tchiani and his followers failed to cede power.

The coup in Niger was driven by several factors, including the growing dissatisfaction with the government’s handling of security issues, particularly the rising threat of terrorism. The military voiced its concerns that the civilian government was not doing enough to address security threats and protect the country’s 24 million residents. In addition, allegations of embezzlement and the mismanagement of public funds strengthened perceptions of government corruption. With public trust and support for the government eroding, a coup d’état became increasingly likely.

Concerns about the lack of economic development and high unemployment rates have a clear basis. While Niger boasts some of the world’s largest uranium deposits, it is still one of the most heavily indebted poor countries (HIPCs), relying on subsistence agriculture such as livestock and farming, and the export of raw commodities. These ongoing challenges combined to create a volatile situation that has now led to the military coup in Niger.

Niger and the War on Terrorism

Savell notes that Niger’s strategic geographic location has made it an important player in the Global War on Terror. Before the attacks of September 11, 2001, Niger, like many other countries in West Africa, was not a major focus in terms of terrorism. The international community provided minimal military aid to Niger as the country was not a strategic priority in the fight against political and religious extremism.

The Republic was primarily known for its struggles with poverty, corruption and political instability. The Government of Niger faced various challenges, a series of military coups, and a lack of effective governance among them, but terrorism was not considered a significant threat in the region at the time.

After the targeted terrorist attacks of 9/11 against the US, the global landscape changed dramatically. The US launched its fight against terrorism, targeting disruptive groups, their leaders and their supporters worldwide, including countries like Niger in the Sahel region due to its proximity to known jihadist groups and the consequential potential for recruitment and radicalisation of its inhabitants. The US increased its military aid to Niger, provided support for counterterrorism efforts, and built the capacity of local security forces to enhance Niger’s ability to combat terrorism and prevent the spread of extremist ideologies within its borders.

Coup du jour

The US has provided a great deal of military aid to Niger over the years, while considerably less infrastructure and development support has been provided. This has included sending US trainers and advisors to assist local military officials. Security assistance and weapons have outpaced earlier infrastructure and development support.

According to one report, US-trained officers who participated in Flintlock, the US Africa Command’s largest annual special operations exercise, have conducted at least five coups in the last eight years. According to Turse, an investigative reporter, these “officers have attempted at least nine coups (and succeeded in at least eight) across five West African countries, including Burkina Faso (three times), Guinea, Mali (three times), Mauritania, and the Gambia” since 2008.

This has had significant political ramifications for the region. Coups have also taken place in Mali and Sudan. The involvement of US-trained military officers in these coups raises questions about the potential unintended consequences of military support. While the US provides military training to foster security and stability, the participation of these officers in coups undermines these objectives and contributes to political turmoil.

A history of colonialism and its aftermath

To understand the complexities of Niger military coups, one must delve into the historical context of the region. Niger, like almost all African nations, has long grappled with the legacy of colonialism and its aftermath. As a former French colony, Niger’s political landscape bears the imprint of its colonial past. The influence of France in the region, both politically and economically, has shaped the dynamics of power and contributed to a sense of resentment among factions within the military.

Niger gained independence in 1960 after more than six decades of French rule. However, Zambakari reports that the form of colonial governance in terms of the centralisation of power in the hands of a few elites has persisted. During Niger’s colonial period, the French established a system of direct and later indirect rule whereby local chiefs were appointed as intermediaries between the colonial administration and the population. The system continued after independence, with power concentrated in the hands of a small group of politicians and military officials. The corresponding lack of inclusivity in governance has been one of the underlying causes of discontent among the population, leading to political instability and ultimately, military coups.

Furthermore, French rule in the African colony relied on Niger’s extractive industries as a source of revenue, particularly uranium mining. The French continued to exploit Niger’s rich mineral resources even after independence through various agreements and partnerships. French extraction of uranium in Niger goes back several decades. Over the past ten years, the 88,200 tons of natural uranium imported into France came mainly from three countries: Kazakhstan (27 percent), Niger (20 percent), and Uzbekistan (19 percent). Orano, a 90 percent French State-owned nuclear energy company, has major stakes in three uranium mines in Niger.

Tharoor notes that Niger is the world’s seventh-largest producer of uranium, possesses Africa’s highest-grade uranium ores, and is one of the main exporters of uranium to Europe. France, the country’s former colonial ruler, is a major importer of Nigerien uranium, which helps power the massive French civil nuclear industry. This exploitation and reliance on natural resources has resulted in economic inequality and limited diversification within the economy, leaving many Nigeriens marginalised and discontented. The military junta thus cited the “continually deteriorating security situation” and “poor economic management” as the main reasons for the most recent coup.

French colonial rule also left a legacy of weak institutions and limited governance capacity in Niger. The ruling French administration focused primarily on maintaining control over its West African colony and extracting its resources, rather than building strong institutions or investing in human capital. This lack of institutional capacity has hindered Niger’s ability to govern itself and address the needs of its population effectively. The military coup can be seen as a reflection of this governance deficit, as well as a desire for change and reform.

In contrast to military assistance, US development aid to Niger has been limited and may further decrease in future. Development aid generally focuses on long-term sustainable development, tackling poverty and instability’s root causes. While Niger grapples with challenges like food insecurity, droughts, and inadequate infrastructure, US aid has been modest compared to military support.

This disparity reflects the prioritisation of security concerns over forward-thinking development goals when viewed in the context of the War on Terror. However, it is very important to find the right balance between dealing with current security threats and addressing socio-economic issues that fuel instability and radicalism in the area. An all-inclusive approach that combines military and development aid is indispensable for accomplishing long-lasting peace and stability in Niger and other West African countries that have been affected by the attempts to defeat terrorism.

Beyond the political ramifications, the Niger coup has had profound humanitarian consequences, including the displacement of as many as 335 000 people as well as forcing about 4.3 million people to turn to aid to survive, exacerbating an already-dire humanitarian crisis in the region. The US suspension of foreign assistance programmes benefiting the Government of Niger (originally offered dependent on democratic governance), as well as the disruption of vital services, such as healthcare and education, has further deepened the suffering of the Nigerien people.

The role of international actors in the Niger crisis cannot be overlooked in the examination of the unrest expanding outward from the capital city of Niamey. The US and France, as key players in the region, have a vested interest in maintaining stability and combating terrorism. However, some critics argue that their influence in the region has inadvertently contributed to the tensions and divisions that led to the coup.

Conclusion

The military coup in Niger has laid bare the challenges faced by West Africa in its quest for stability and democracy. The complex interplay of historical, geopolitical and security factors has contributed to the current crisis, threatening to spill over into neighbouring countries and impede the promotion of democratic governance in the region. As the international community grapples with the implications of the coup, it must work together to support Niger in its journey toward peace, stability and inclusive governance.

The coup must be seen as a manifestation of complex dynamics shaped by French colonial statecraft and the US legacy of the War on Terror. French colonialism in Africa has left a lasting impact on the political and economic landscape of countries like Niger.

The coup can be seen as a response to the deep-rooted issues of corruption, inequality and governance that have plagued the country since independence. Additionally, the US War on Terror, with its focus on counterterrorism efforts in the Sahel region, has inadvertently contributed to the militarisation of politics in Niger. The heavy reliance on security forces has allowed military leaders to consolidate power and exploit the rampant vulnerabilities within the political system.

Regional organisations such as Ecowas, with the support of international partners, must redouble their efforts to mediate and find a peaceful resolution to the crisis. This will require addressing the underlying grievances of marginalised groups, promoting inclusive governance, and fostering economic development.

The next step is looking beyond the paradigm of the War on Terror with its focus on security assistance at the expense of development aid. In the end, addressing the root causes of instability and factors that motivated the coup is one way to break the cycle of recurring coups. By investing in education, infrastructure, and job creation, the international community can provide the Nigerien people with a sense of hope and opportunity, reducing the appeal of extremist ideologies.

The military coup in Niger has highlighted the urgent need for a shift in the international community’s approach towards the country. Military interventions and the War on Terror’s security paradigm have failed to bring lasting peace and stability to Niger. Instead, a diplomatic and humanitarian approach is necessary to address the root causes of instability and promote democrati

Dr Christopher Zambakari is CEO of The Zambakari Advisory. He is a Hartley B and Ruth B Barker Endowed Rotary Peace Fellow, and the assistant editor of The Bulletin of the Sudan Studies Association. His area of research and expertise is international law and security, political reform and economic development, governance and democracy, conflict management and prevention, and nation- and state-building processes in Africa and the Middle East. His work has been published in leading law, economic, and public policy journals.

This article was published on ACCORD