Nation of Laws and the language of deception

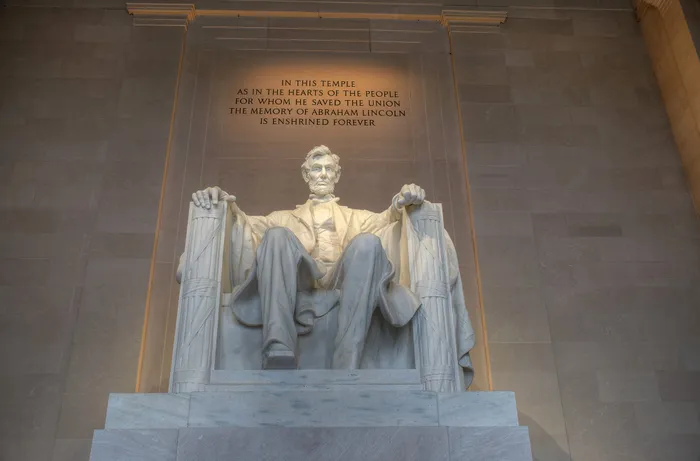

Picture: Creative Commons - licenses - by -sa 4.0 – Along with the ‘nation of laws’ mythology, it is important to perpetuate the belief among the general population that the country does good things around the world when all too often the opposite is true, the writer says.

By James Rothenberg

Are we really a nation of laws? There are two sides to this. One involves the structure and the other the practice. The structure is rock solid. There are laws on the books for practically everything we can think of. Sticking to this aspect, the question almost answers itself.

However, as the expression is used, to be a “nation of laws” must mean that we live by them. It is with this in mind that the question cannot be fully answered until we examine some of the practices.

Laws are made by those that broke the law last. The survivors. The conquerors. We still have a vivid example in our American Southwest. Elected law enforcers speak of Mexicans sneaking into our country as “illegals”. Being “illegals”, they don’t belong here, right? Straightforward enough. But what do we do with the entire remaining population of the Southwest? They’re living on stolen land. They’re the original illegals.

The end of World War II marked the beginning of the UN Charter, dedicated to trying to eliminate the possibility of the world having to endure another war. The Charter is the supreme instrument of international law, binding upon all the world’s nations.

Kofi Annan, then UN Secretary General, was pressed to answer if the US invasion of Iraq in 2003 was illegal. He responded that it was, from the point of view of the UN Charter. Why “from the point of view”? Well he was Secretary General, so it was in his province to refer to it. Everything that is illegal is illegal in reference to something that has been previously set down.

Still, his response could have been more concise. He could have plainly replied, yes, it’s illegal. In not doing so, he places some distance between illegality and possible criminality. “From the point of view” of the Charter becomes a technicality, perhaps even something to be argued over.

Going further, he might have replied that the US invasion was illegal from the point of view of US law. Like said, that wasn’t his province, but he would have been correct. Our Constitution says as much, and obliges all the judges in our land to enforce the UN Charter. Now we’re getting even more technical but when you break someone’s nose, you’re breaking it technically as well as physically. That’s why you’re not supposed to do it.

Secretary of State Antony Blinken just provided a good example of the above. The media claims that he called Israeli settlements illegal. He did not. He said the settlements are “inconsistent with international law”. What’s the difference? Illegal is illegal, but “inconsistent with international law” can be argued about. For days, for months, for years and even decades. It makes all the difference because the technical euphemism distances illegality from actually having to do something about it.

Blinken, with a straight face, called it a reversal of policy, ignoring that 46 years ago his State Department also declared it “inconsistent with international law” (which hasn’t changed) in that “territory coming under control of a belligerent occupant does not thereby become its sovereign territory”.

Revealing how easily practice of the law can be separated from the structure of the law, five years ago then US State Secretary Mike Pompeo said the settlements are no longer considered a violation of international law. It’s a mark of how much pressure our State Department is under when Blinken legitimises Pompeo’s counter-factual statement on the settlements, and can’t speak in plain language about them.

Along with the “nation of laws” mythology, it is important to perpetuate the belief among the general population that the country does good things around the world, central to which is liberating people from authoritative regimes by the spreading of democracy. Without access to the actual historical record — which starkly contradicts this — the story of our foreign policy is a subject of extreme bias.

The difference between official policy (that which is put out publicly) and unofficial policy (that which is concealed from the public) is stark. This feature is not unique to our own country. States are not self-managing. They all operate on hierarchal principles. The function of a ruling hierarchy — even a democratic one — is to render subservient the people beneath. No state could function otherwise. This is best managed by convincing people that they are not subservient. That is the role propaganda plays in controlling the population.

The difference between official and unofficial policy rarely becomes acknowledged, but just recently Joe Biden spilled some beans. At pains to get Ukraine funding past recalcitrant Republicans, Biden takes his case to the public. He wants us to know that nearly two-thirds of the money will not be spent in Ukraine but “… right here in the United States of America in places like Arizona, where the Patriot missiles are built; and Alabama, where the Javelin missiles are built; and Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Texas, where artillery shells are made”.

How much pressure is Biden under to speak this clearly? Americans are led to believe that foreign aid is given out of beneficence, not to benefit certain sectors of our own economy. That’s why polls reveal that most Americans feel that we give too much money away to foreign countries, so much so that they drastically overestimate how much it really is. It’s largely concealed that the majority of foreign aid actually ends up right here.

With this amount of candour in place, perhaps Mr Biden can extend this to another truth-teller, Julian Assange, ill and languishing in a British prison awaiting extradition to the United States for revealing US war crimes. Yeah, they’re illegal, from any point of view.

On a personal note, I confess to being more drawn to universal (national, international) themes than parochial (local) ones. The justification for favouring this in print is twofold. One, that the larger view is more informative of the smaller, than the reverse. Two, of the two, the universal is the more easily missed.

James Rothenberg, of New York State, is a member of Veterans for Peace.

This article was published on Common Dreams

Related Topics: