Marcus Garvey, Mao Tse-Tung and Gandhi

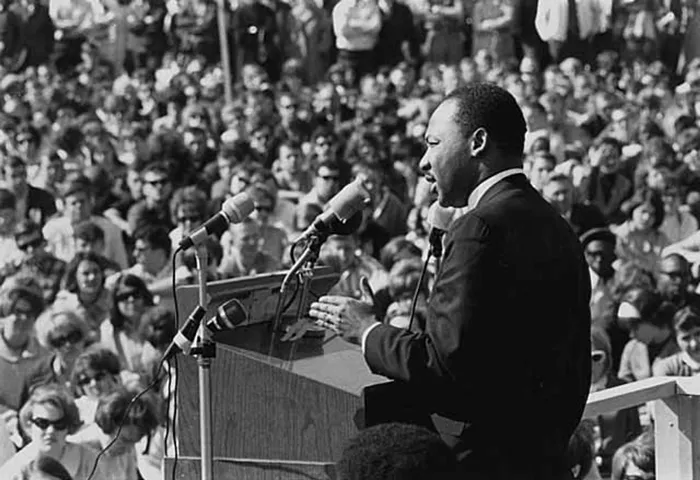

Dr Martin Luther King Jr speaks to an anti-Vietnam war rally at the University of Minnesota in St Paul, US, on April 27, 1967. The movements that gave us modern India, China, and Black America were, for a time, deeply conversant with one another, the writer says. – Picture: Wikimedia Commons

By Eugene Puryear

The movements that gave us modern India, China, and Black America were, for a time, deeply conversant with one another.

Jawaharal Nehru was a lifetime member of the NAACP, whose founder, WEB Du Bois was on friendly terms with Mao Tse-Tung. James Lawson, a Black Methodist minister, who refused to fight in Korea, travelled to India, studied Gandhi, and later brought his teachings to the Civil Rights Movement.

China would name Paul Robeson the chairperson of its relief efforts in World War II. He would then go on to publish a newspaper in the heart of McCarthyism tying these strands together.

Amidst the rise of the “Asian Century” and the era of Black Presidents, the legacies of those movements are in danger. Risking being turned into a caricature by the Cold War politics, a fascistic upsurge, and the fragmentation of the world into a poorer, hungrier, more dangerous, and less liveable place, recovering stories from an earlier time, underpinned by a more liberatory vision, helps us find reference points for our movements and parties to conduct the radical course corrections needed to save humanity.

Haryana to Harlem

In 1948, a journalist travelling in India reported:

“When I asked some farmers in a village in West Bengal how they felt about American assistance to “raise the standard of living of people in underdeveloped areas such as India, one elderly farmer replied: ‘We will believe in America’s altruistic motives after we see the American government raise the living standard of the Negroes and extend to them full justice and equality’.”

This consciousness of Jim Crow policies was rooted in a long history of interaction between the Indian freedom movement and Black America.

A 1922 report from US Naval Intelligence noted with concern: “the present Hindu revolutionary movement has definite connection with the Negro agitation in America”. They took note of the African Blood Brotherhood, whose leader, Cyril Briggs, noted the Indian Freedom Movement as one of a few “factors” that “help us here, right here in Harlem”.

Two days after Gandhi was sentenced for sedition, also in 1922, Marcus Garvey mounted the rostrum at Liberty Hall in Harlem and declared that the “imprisonment of Mahatma Gandhi will ultimately pave the way for a free and independent India”. A few of Garvey’s telegrams to Gandhi made into the pages of Young India as examples of the international support being garnered by the freedom movement.

The name of Gandhi’s journal came from a book by Lala Lajpat Rai, an early member of the Indian National Congress who had been active in independence struggles since the 1880s. Travelling in the United States Rai “was shocked by [the] treatment of the Negro” and worked to build ties between India and Black America, making contact with WEB Du Bois.

Du Bois considered Rai, a “personal friend of mine … he was at my home and in my office and we were members of the same club”. Rai, looking to raise awareness, wrote to Du Bois in 1927 for “any recent literature which you can send me about the treatment of Negroes in the United States and also about the activities of the Ku Klux Klan”.

“I have a few new numbers of the Crisis from 1917 to 1920 from which I am going to quote profusely.”

Rai modelled elements of his cadre training school, The Tilak School of Politics, on Tuskegee University, the Historically Black College founded by Booker T Washington who Rai also knew.

After Rai was killed by British forces in 1927, Du Bois wrote to a Lahore newspaper: “When a man of his sort can be … beaten to death by a … government, then indeed revolution becomes a duty to all right-thinking men.”[7]

Across the Pacific

From the mid-1920’s to the early 1930s, thousands of Black students joined the segregated “Coloured Work Department” of the YMCA. The organisation’s “respectable” nature, but international scope made it a place where students eager to break out of the Jim Crow prison could discuss “global inequalities” in light of “racial prejudice, economic inequality, and political unrest in the United States”.

The YMCA and allied Christian organisations were also active in China. Through conferences Black and Chinese strugglers were able to build ties. The Student Association Newsletter, the organ of Black YMCA youth, encouraged their readers to form study groups on campus to study China and “international-political imperialism”. They also raised their voice in protest after five thousand US Marines were sent to China in 1927.

The same year, In Nashville, an integrated student event “denounced in strong terms the imperialistic policies of the United States” towards China. The Chicago Defender, the largest circulation Black newspaper in the US, reported that the “scholarly” presentation framing discussion on China was given by Malcolm Nurse, better known to history as George Padmore.

The Defender also reported to its readers the contents of a speech to students at Historically Black Virginia State College in 1932 by TZ Koo, a Chinese nationalist, detailing the causes and effects of the Japanese invasion of China in 1931.

Solidarity from the Left

Langston Hughes would be one of the first Black artists to tour China in 1934, something of great interest to him since a trip to Moscow in 1932, where he met Si Lan Chen, daughter of Eugene Chen, one of China’s most prominent, and radical, diplomats.

Paul Robeson would also mention the Chens as having an impact on his views when they met during a 1934 visit to the USSR. Black Communist Harry Haywood relates in his memoir how during his time as a student at a Party school in Moscow, China contributed the “largest group” of students.

Robeson’s connections to the broader Communist milieu also brought him into contact with Rajni Patel, a close friend of Nehru, and, at the time a communist. Robeson would write the introduction for Patel’s pamphlet “Brother India”.

In his contribution Robeson states: “This struggle of 370 million Indians is a great message of hope to the Negro people … Above all we can see that the people who are struggling for freedom in India and in China and in South Africa are the best allies.”

The Chicago Defender, part of the Communist anchored Popular Front, propounded similar themes. In October of 1937 alone the Defender ran three articles drawing parallels between the fight to defend China with the fight to defend Ethiopia from Italian aggression.

People’s Voice —a joint project of the communists and civil rights leader Adam Clayton Powell — read by 40,000 to 50,000 Black New Yorker’s a week, often used the slogan “Free India, Free China, Free Africa!

In 1958, in cities across India, Paul Robeson’s birthday was celebrated in festivities organised by a high-level committee. The New York Times reported that “Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and his daughter are giving warm support to a nationwide campaign to honour Paul Robeson” for his contributions in the “cause of human dignity”.

Robeson’s Freedom newspaper reported in July of 1951 that “Indians, individually and in mass meetings, have protested against the treatment of the Martinsville Seven, the Trenton Six, the denial of a passport to Paul Robeson and the indictment of Dr Du Bois.”

Similarly, in the early morning of April 18, 1968, people were “gathering in workplaces, schools and neighbourhoods” all across China. Making preparations for mass rallies to show support for Chairman Mao’s statement, “In Support of the Afro-American Struggle against Violent Repression,” released shortly after Dr Martin Luther King Jr’s assassination, when uprisings were raging across the US.

“In Shanghai alone, one million people turned out to express their unity with the embattled Black Americans.” Chants like “Oppressed nations and peoples of the world, unite! … Down with the reactionaries of all countries! … Support our Black brothers and sisters!” rang out. It was duplicated in “major cities…and autonomous regions, including Tibet, involving many millions of people in all.”

Non-cooperation and the Civil Rights Revolution

Howard Thurman was one of America’s most prominent Black theologians in the 30s and 40s, serving as the Dean of Howard University’s Rankin Chapel. Thurman had close ties with the Fellowship of Reconciliation, an international network of Christian socialists.

FOR arranged a “Pilgrimage of Friendship” tour of India in 1935-1936. All across India, Thurman, his wife and others lectured on topics ranging from “American Negro Achievements” to “Internationalism in the Beloved Community”.

The delegation met with Gandhi for three hours. Thurman related that “never in my life have I been a part of that kind of examination”. Gandhi had “persistent, pragmatic questions about American Negros” asking about “voting rights, lynching, discrimination, public school education, the churches and how they functioned”.

Before they left, Gandhi sang spirituals with the delegation and said, as they left, “It may be through the Negroes that the unadulterated message of nonviolence will be delivered to the world.”

Gandhi was not far off as the story of James Lawson, a Black college student in Ohio, shows. Affiliated with the Fellowship of Reconciliation, he refused to register for the draft in 1951 in opposition to the Korean War.

Following his parole in 1952, he went to perform missionary work with the Methodist church in India and studied Gandhian non-violence closely. In 1957, he crossed paths with Martin Luther King Jr fresh off the Montgomery Bus Boycott, and despairing at the movement’s lack of experience with non-violent tactics.

Knowing Lawson had studied with Gandhi’s disciples, he implored him to come South: “come now”. “Don’t wait. We need you now.”

Lawson would soon after move to Nashville, and started training Black students in non-violent tactics in what would become known as the Nashville Student Movement, through which many of the most well-known activists of the Civil Rights era: John Lewis, Diane Nash, James Bevel, Marion Barry and others got their start.

Tomorrow is more important than yesterday

Much can be gleaned from the vignettes above, which just scratch the surface of how these struggles intertwined. Speaking from my perspective, as a Black communist in the US, it speaks powerfully to our current moment.

How a renewing of the ties of Black-Palestinian solidarity, at the grassroots, built relations and understanding that helped a renewed Palestinian solidarity movement become an undeniable force in the political and social life of the Imperial centre.

How can we do the same for the workers and the farmers in India, the political prisoners and the people of Kashmir? How can we coexist with China rather than ignore our complementarities for a mutually impoverishing Cold War that could turn hot?

Relatedly, how can we do more for the future Breonna Taylors in Mumbai and turn China’s new role in global governance towards the cause of reparations?

However we may succeed in these tasks and more, it will likely be through the combination of direct interventions, like the practical solidarity that filtered into the streets of Ferguson from Palestine through social media. And building on the existing foundations and histories left by the freedom fighters before us.

Eugene Puryear is a journalist at the US movement-centred Breakthrough News and a member of the Party for Socialism and Liberation. He also writes for Peoples Dispatch