Mandela dreamt of an African Renaissance

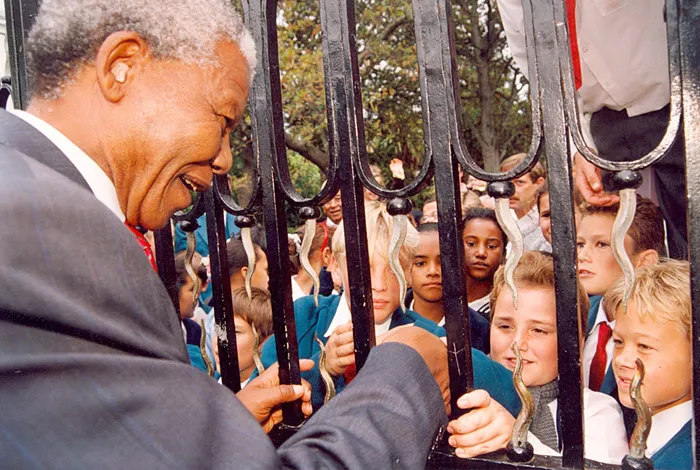

Picture: Leon Muller/Independent Media Archives – Nelson Mandela, the People's President. World icon, statesman, freedom fighter, father of the South African nation- Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela was a South African anti-apartheid revolutionary, political leader, and philanthropist who served as President of South Africa from 1994 to 1999. He was the country's first black head of state and the first elected in a fully representative democratic election. He died at the age of 95 on December 5, 2013 from a prolonged respiratory infection.

By Kim Heller

Nelson Mandela dreamt of an African Renaissance. Of an Africa that would no longer “knock on somebody’s door pleading for a slice of bread”. He contended that there was no obstacle large enough to stop such a renewal.

He expressed these sentiments at an Organisation for African Unity (OAU) meeting of Heads of State and Government held in Libya way back in June 1994. It was barely a month after he was inaugurated as the first democratically elected President of South Africa. Hope was in the air. A fragrance so liberatory, so beguiling, and so very misleading.

Twenty-nine years later, as we mark Mandela Day, his dream has yet to be fulfilled. There is no revival of African prosperity or rebirth of African supremacy and self-determination. The African dreamscape remains caught in the nightmare of poverty, ravage, and war.

Mandela delivered an impassioned speech at the 1994 OAU meeting. He spoke of how in the ‘distant days of antiquity’, a Roman had sentenced the African city of Carthage to death. “Today,” Nelson Mandela said, “we wander among its ruins, only our imagination and historical records enable us to experience its magnificence. Only our African being makes it possible for us to hear the piteous cries of the victims of the vengeance of the Roman Empire.”

In his address, Mandela spoke of how when Carthage was destroyed so many epochs ago, the children of Africa were carted away as slaves, of how African land became the property of others, and how the resources of Africa were extracted and enriched faraway nations. Mandela spoke of an Africa on its knees, its people defeated, reduced to beggars and at the mercy of Western powers.

He then told the gathering of how the ancient pride of the African people had asserted itself, through inspired leaders such as Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, Patrice Lumumba of Zaire, Amilcar Cabral of Guinea Bissau, Samora Machel of Mozambique, and Albert Luthuli and Oliver Tambo of South Africa. These leaders, Mandela said, had helped to herald in political liberation across the Continent and put an end to the “long interregnum of humiliation”.

“Africa cries out for a new birth,” Mandela declared, for she has “shed her blood and surrendered the lives of her children so that all her children could be free.” He continued, “A million times, she put her hand to the plough that has now dug up the encrusted burden of oppression accumulated for centuries.”

Mandela paid tribute to the OAU and the Heads of States. He said, “We are here to salute and congratulate you for a most magnificent and historical victory over an inhuman system whose very name was tyranny, injustice and bigotry”. Mandela spoke of how the contributions made by so many individuals, across multiple African nations, in the fight for freedom are as “measureless as the gold beneath the soil”.

In his address, Mandela spoke of how the total liberation of Africa from foreign and white minority rule had been achieved. But it was not so in 1994 when Mandela delivered this powerful speech. Nor is it so in 2023.

Mandela wished for a rebuilt African economy where patterns of dependency, including being net exporters of capital are rooted out, and where the deteriorating terms of trade no longer impair the Continent’s capacity for self-reliance. He dreamt of sustained development on the Continent, not one fed by nations across the Black Sea.

The African Renaissance envisaged by Mandela is a faraway land. In his OAU address he spoke of how Carthage awaits the restoration of its glory. He said, “If freedom was the crown which the fighters of liberation sought to place on the head of Mother Africa, let the upliftment, the happiness, prosperity and comfort of her children be the jewel of the crown.”

Despite the most noble and courageous battles for liberation, and the selfless sacrifices made by leaders and ordinary people across the Continent, Africa is yet to be free. Rather than renaissance, much of the Continent is still caught in a nightmarish paralysis. In the words of Italian revolutionary, Antonio Gramsci, “the old world is dying, and the new world struggles to be born now: is the time of monsters”.

Mandela said that when the history of the struggle is told, it will tell of “a glorious tale of African solidarity, of the sacrifices made to put an end to the injustice, insult and degradation of Africa and her people”. But for now, this is a dream that appears out of reach.

In his final address to Parliament as President of South Africa, Mandela said, “I am the product of Africa and her long-cherished view of rebirth that can now be realised so that all of her children may play in the sun.”

Whether the Continent will ever free itself from foreign and white minority rule is a tale that future generations of historians will tell. For now, the chains remain heavy as Africa is caught in the desperate economics of begging bowl dependency on the very foreign nations that stripped it of its wealth and wellbeing.

In the same way the Roman Empire sentenced the African city of Carthage to death so many ages ago, many African leaders today are destroying their own cities, through their deadly dependence on foreign nations, internal conflicts, and disunity. Today, Africans wander through a Continent of great ruins.

Kim Heller is a political analyst and author of ‘No White Lies: Black Politics and White Power in South Africa’.

This article was written exclusively for The African. To republish, see terms and conditions.

Related Topics: