Harry Belafonte’s biggest hit? The song of freedom

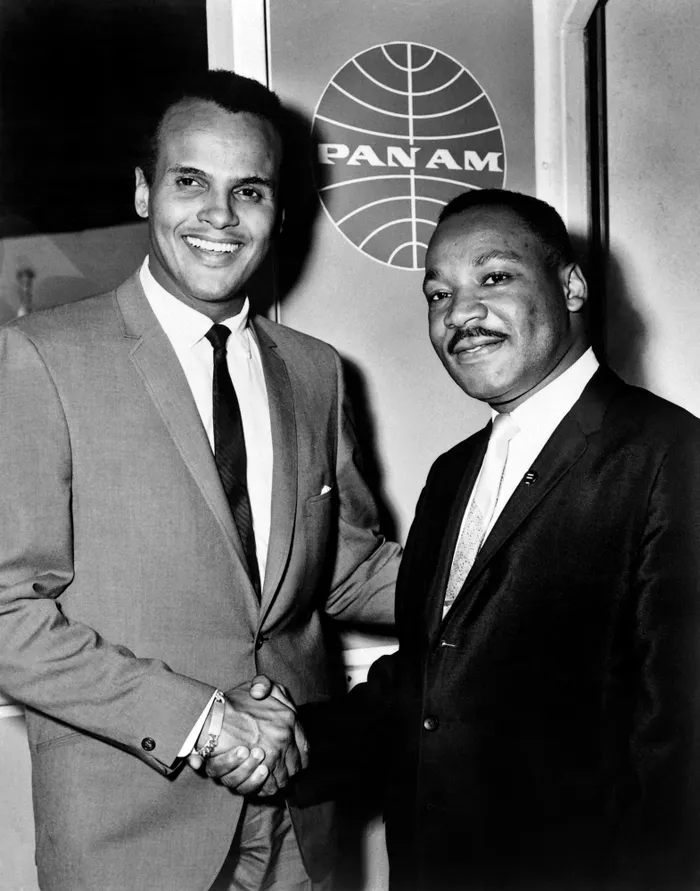

Picture: AFP – Harry Belafonte, left, with Martin Luther King on August 21, 1964, at New York’s JFK International Airport.

By Wil Haygood

It was one of those lovely autumn days in Manhattan. I had anchored myself two blocks away from Harry Belafonte’s office, sitting at the front window of a diner. For several months I had been trying to arrange an interview with him.

I was chasing the life of Sammy Davis jr, whom Belafonte had known and offered advice to about the entertainment industry for black people in the 1950s. Sitting inside that diner I fretted that the interview might be cancelled. As I gazed out the window, however, a tall, caramel-coloured figure strolled right by. I blinked. Harry Belafonte! He was obviously going to his office. To meet me!

I raced from the diner, galloped wordlessly on the street right by Belafonte, and positioned myself in the foyer of his office. He entered and strolled right by. An assistant soon ushered me to a small conference room. Belafonte entered. “Didn’t I see you run past me on the street?” Those were the first gravelly-voiced words he said to me, and we chuckled.

For the next two hours, Belafonte proceeded to take me into the world of black entertainment as it played out during his lifetime. It was a personal journey, both dangerous and triumphant. His death on Tuesday, at the age of 96, is a colossal loss for the culture of America and the world.

To fully appreciate Belafonte, the raw truth needs to be told. Because he was America’s first modern black male sex symbol, he frightened and entranced white America. The men with jealousy; the women with adoration.

His parents were Jamaican, and that island pride seems to have imbued him with a certain cockiness. He talked back to naval superiors when he served during World War II and got tossed in the stockade. He later trained for the stage in Harlem (Sidney Poitier was a classmate) and soon found himself on Broadway and performing in nightclubs.

It was in the afterglow of a stage performance that Belafonte met Paul Robeson – a titanic figure, a collegiate All-American in football, an actor, and a figure who frightened State Department officials because of his travels to Russia. Communism was a witchy word. In the bruised figure of Robeson, Belafonte found his mentor. “What I remember, more than anything,” Belafonte would write of Robeson in his autobiography, “was the love he radiated, and the profound responsibility he felt, as an actor, to use his platform as a bully pulpit.”

His contemporaries always talked of the “Belafonte magnetism”. Jazzmen – Charlie Parker, Max Roach, Lester Young – all wanted to help him when he was starting out. He benefited from the music world – especially when he sang folk songs – and it widened his fan base.

Hollywood, however, was a different matter. The town did not know how to use black and handsome Belafonte. He appeared alongside Dorothy Dandridge – bruised as much as Robeson because of her race, which she impossibly tried escaping – in Bright Road, a 1953 film set inside a school that implausibly ignored the issue of race. So he kept singing. By the late 1950s, Belafonte had become an international singing sensation.

Time magazine put him on its March 2, 1959, cover. But it was his association with the young Martin Luther King jr, begun in 1956, that gave Belafonte the ballast he seemed to crave in life. King was crisscrossing a segregated nation, preaching from the pulpits, issuing warnings about the nation’s very survival. Belafonte, like King, bemoaned the fact that black people were living “under the hammer”, as he put it.

What King needed to keep the civil rights movement going was money. And Belafonte told him he would help him raise that money. Perhaps it hasn’t been written about enough, or deserves to be written about more, but $1 and $5 bills were so crucial to the civil rights movement. Black church congregations folded bills hidden inside envelopes and sent the money to the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, to the Student Non-Violent Co-ordinating Committee, to the NAACP (the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People), to CORE (Congress of Racial Equality). Black farmers rode mules to rural post offices and sent cash to offices that they’d never see in their lifetimes.

Someone would spot Belafonte in an airport. They’d sing a stanza from Matilda or The Banana Boat Song and he’d listen and smile. Then he’d wonder if they had a little contribution to “the movement”. This is how the Belafonte magic worked: King would call for marchers, in Georgia and Alabama or Mississippi or Florida.

Yet another white voting official had told a black woman she could vote if she guessed how many jellybeans were in a jar on the table next to her elbow. She guessed wrong. She always guessed wrong. So, the next day a march would be called. And arrests would be made, kids right along with adults. Then with his precious phone call, King, often jailed himself, would reach Belafonte. And Belafonte would go into action. He’d hit up the likes of Leonard Bernstein, Marlon Brando, Ossie Davis, Joan Baez, James Garner and Sammy Davis jr – all friends of the movement.

King and Belafonte grew enamoured of Davis, who would end up being a kind of secret financial weapon of the movement. On that Manhattan day, in that conference room, standing on his feet, pacing, Belafonte kept returning to Selma, Alabama. He talked about the pain of the first Selma to Montgomery civil rights march, which took place on March 7, 1965.

Marchers were beaten and bloodied by white law enforcement; much of the nation had watched newsreel footage and were aghast. The second march, on March 9, was aborted shortly after it began. A third march was announced for March 21. President Lyndon B Johnson promised the presence of federal troops to guard the marchers.

King told Belafonte he needed an infusion of cash, and quick. “Get Sammy,” King told Belafonte. Davis was on Broadway, appearing in Golden Boy. Belafonte reached Davis, who was quick to make a large financial contribution. But Belafonte told Davis that King wanted more: he wanted Sammy’s presence in Selma. On that bridge. Marching with the protesters. It would be good press! Davis sighed. Married to former actress May Britt at the time, a white woman from Sweden, he had received hate mail from bigots. “They’re going to kill me,” Sammy said about white Southerners.

The Golden Boy producers didn’t want to tell Belafonte of Davis’s reticence, so they told him the production simply couldn’t afford to have him miss a performance. Counting the money he had raised – a lot of it from Davis himself – Belafonte offered to buy out the night’s performance. And there they were, marching across the Selma bridge; Belafonte, humming and singing, Davis in a tweed coat and pork pie hat, and thousands more, a multiracial army.

That night, Belafonte watched Davis stand atop a coffin – their makeshift stage – and sing The Star-Spangled Banner. There were tears. So, let us remember Belafonte not for Hollywood, but for Selma, and his epic role in trying to push a racially haunted nation forward.

This article was first published in The Washington Post