GNU negotiations expose the deep-seated political historical fault lines and immaturity of our politics

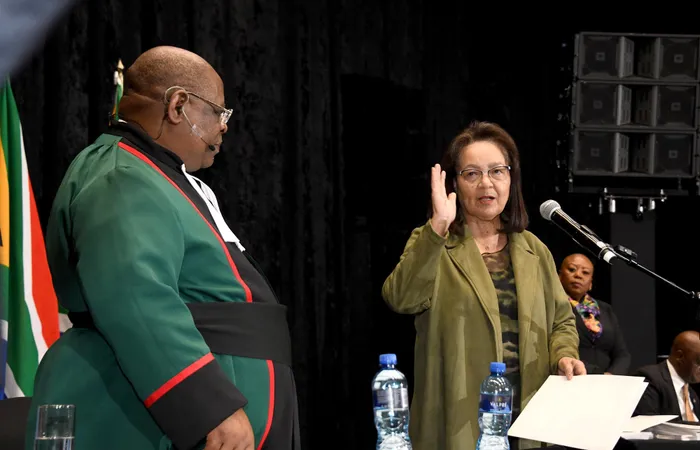

The new minister of Tourism from the GOOD party, Patricia de Lille, at the swearing-in ceremony of the incoming deputy president, cabinet ministers and deputy ministers at the Cape Town International Convention Centre, Cape Town. The new national executive constitutes the 7th Democratic Administration as a Government of National Unity comprising diverse political parties, the outcome of national and provincial elections on May 29, 2024. – Picture: Kopano Tlape / GCIS / July 3, 2024

By Sello Moloto

The national and provincial elections of 2024 exposed the extent of the political polarisation and the immaturity of politics in South Africa. The opposition parties have succeeded in bringing the ruling party below 50 percent but yet failed to form a government.

It is inexplicable that political parties which constitute 60 percent of the 2024 electoral support do not even attempt to form a government without the ruling party although their election platform was based on removing the ruling party from political power, vowing not to do anything with the ruling party.

Part of the reason we find ourselves in this conundrum is because our leaders went overboard with their election campaign messages. The election campaign messages ranged from “2024 is our 1994” to “doomsday coalitions”.

If you did not know the characters, you would be mistaken to think that their campaign messages were meant for a country which is foreign to you.

The election campaign messages demonstrated the deep-seated political fault lines of polarisation which characterise our body politics and the general political health of our nation. The political differences go beyond what can be regarded as healthy political, and ideological differences, but hinge on bad blood and hatred among political leaders.

The inadequacy of politics and politicians in the low-income (developing) world is the lack of understanding that politics involves competition and co-operation. Politicians in the developing world believe in permanent competition. In the high-income (developed) world, politicians understand that holding a different political view does not make you an enemy.

Healthy politics involves competition (election campaigning) and co-operation (constructive opposition). The opposition parties in the developed world understand the need to co-operate with the ruling party after the elections. The culture of concession of defeat by party leaders has been developed to send a message to their supporters that political leaders are not enemies and therefore need to co-operate in the best interests of the country.

The contest for political power and office should be likened to soccer teams competing for a league title championship. The soccer team which grabs the championship trophy at the end of the season does not make the other clubs less important. The club which wins the league championship does so because it proved to be the better team that season.

Politicians can learn one or two things from soccer players. The players understand and internalise their trade to a point where over and above shaking hands at the end of the match, they even exchange their jerseys as a sign of respect and appreciation.

This sportsmanship attitude makes it easy for them to co-operate when they are called upon to play in the national squad. Our political leaders must learn that there is a bigger fight out there to promote and advance our national interests. Foreign governments do not differentiate between political parties in pursuit of their national interests.

The public discourse and debates which have been raging on since the declaration of the election outcome expose the depth of polarisation in the country. The anger and frustration displayed in society is palpable and calls for urgent action aimed at nation-building and social cohesion.

There is generally a negative national mood characterised by a huge distrust of politicians and political parties. The social and economic development indexes depict South Africa as an abnormal society.

South Africa is regarded as one of the most unequal societies with the highest unemployment (32.99 percent) and poverty (55.5 percent) levels, with a Gini co-efficient of 0.67. It remains a mystery to social development experts why the nation is not experiencing sustained widespread violent social uprisings akin to the recent ones in Kenya or during the Arab Spring.

The above-stated statistics don’t conjure trust and confidence in our democratic dispensation as depicted by the 2024 IEC statistics. The South African eligible voter population is recorded as 42.3 million. It is further stated that only about half (27.8 million) of the eligible voters were registered to vote.

The election outcome records that the actual voter turnout was 58.64 percent amounting to 16.2 million. This implies that more than 40 percent (11 million) of registered voters stayed away from the polls. These statistics paint a bleak picture for our young democracy.

Notwithstanding the distressing socio-economic indicators, it does not seem like the proverbial “penny dropping” for our political leaders. If anything, the bickering and teetering about the negotiations and debates about the formation of the GNU illustrate a political class which is detached from reality.

The debate about whether the mooted government is a coalition or a government of national unity is not helpful or inspiring any confidence. The reasons advanced that GNU is formed in conditions where there is a national crisis of civil war or strife is an indication that the political class is not in tune with the national mood and the hardship which ordinary South Africans are confronted with daily.

The demands political parties are putting as conditions for participation in the GNU are ridiculous. The arguments are contrary to the reasons why they are saying there should be power-sharing. The parties argue that they are not prepared to work with certain parties but at the same time claim that they respect the outcome of the elections as the will of the people. In essence, such parties are clearly saying they are not interested in the national unity and social cohesion of our nation.

At last, after two weeks of bickering and teetering, the stage is now ultimately set for the GNU. The national executive has been appointed and announced. This does not mean that the road ahead will be smooth sailing due to the immaturity of politics. We should further expect a bumpy ride.

The urgent tasks of this seventh administration will be to rekindle and revive the trust and confidence of the population in state institutions. The GNU should start by going into the cabinet shelves to pull out and dust off policy initiatives and programmes that were abandoned 15 years ago. Programmes such as Masakhane, Vuk’uzenzele, Moral Regeneration and Batho Pele should be revived to instil a sense of active citizenry and patriotism.

The past 15 years introduced a culture of government as a provider of everything and the citizenry as the passive receiver of government largesse. There is a need for a new social contract to push back the frontiers of poverty, unemployment and inequality.

The people must partner with the government to fight crime and all other social ills. A comprehensive social security system is needed to cushion the devastating effects of abject poverty and the rising cost of living.

The work for accelerated economic growth is already cut out for the GNU, the pillars of which will be to unlock the blockages and barriers for the rail, freight and port logistics. The second pillar will involve the resolution of the energy crisis to support manufacturing as an important anchor for the reindustrialisation of the economy. The need for economic growth and job creation cannot be overemphasised.

After all is said and done, one can only pray for two things in the motherland. The first is for South Africans to love their country the same way the rest of the world wishes for its citizenship. The need for patriotism cannot be overemphasised.

The second is for the maturity of our politics. The challenges confronting us require pragmatism to advance our national interests. These prayers are crucial to mitigating the upsurge of anti-establishment right-wing formations masking their destructive populism through left-wing rhetoric and identity politics.

* Sello Moloto is a South African politician

** The views expressed in this article are the writer’s, and do not necessarily reflect the views of The African