Egyptians head to the polls

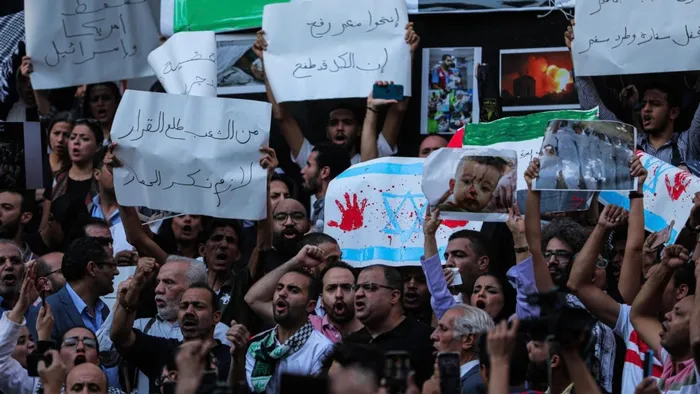

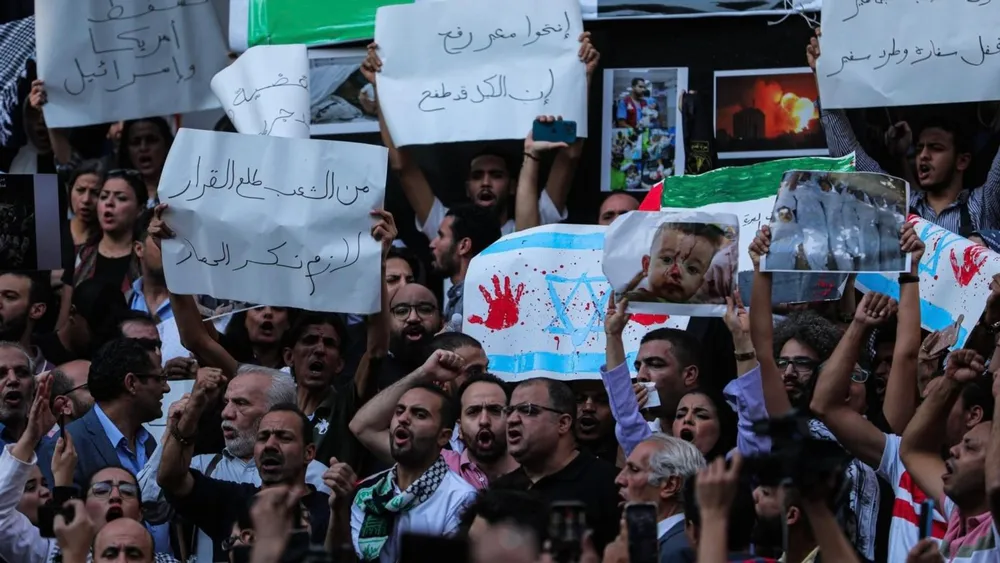

Picture: Eslam Osama / Peoples Dispatch / October 20, 2023 – A protest in Cairo, Egypt against the massacre of Palestinians in Gaza. The people of Egypt have defied repression, persecution to stand with the Palestinian people. Following mass protests in solidarity with Palestine on October 20, over 40 people were arrested by authorities.

Picture: Peoples Dispatch – Egyptian president Abdel Fattah el-Sisi. Egypt will vote from Sunday December 10, 2023 to Tuesday after a decade-long crackdown on dissent that has seen critics from across the political spectrum jailed. The government says the crackdown has been necessary for security and economic stability, despite an ailing economy, the writer says.

By Reuters and AFP

Egypt holds its presidential election from today to Tuesday. The vote comes after a decade-long crackdown on dissent that has seen critics from across the political spectrum jailed.

The authorities said the crackdown was needed to stabilise Egypt and that it targeted extremists and saboteurs working to undermine the state.

President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, a former army chief, has overseen a far-reaching crackdown since leading the 2013 ousting of Egypt’s first democratically elected president, Mohamed Mursi of the Muslim Brotherhood.

He retains the support of a military establishment that has gained further political and economic influence under his rule.

The Muslim Brotherhood, traditionally Egypt’s most powerful opposition force, has been driven underground or abroad.

Sisi is set to secure six more years as Egypt’s president in an election held in the shadow of the nearby war in the Gaza Strip, despite growing unease about the country’s economic performance.

Over nearly a decade in power, Sisi has presented himself as a guarantor of stability in a volatile region, a message that has added traction in a year when two conflicts, in Sudan and Gaza, have erupted on Egypt’s borders.

Politically, the Israel-Gaza war was a “God-given gift, despite all the misery … which allows side-lining the entire presidential election story”, said Khaled Dawoud, a leading member of the Civil Democratic Movement, a coalition of opposition parties and figures that have fractured over whether to boycott or compete in the election.

“It’s a wonderful opportunity for the president to rally support around him, especially at a time of economic crisis.”

Sisi had announced that his campaign would be curtailed to save funds for aid to Gaza, though giant posters showing his face have proliferated on roadsides and buildings.

Sisi’s campaign office did not respond to requests for comment.

Preparations for elections in the Arab world’s most populous country are massive in scale – with nearly 9 400 polling stations set up and 15 000 judicial employees working over the three days of voting.

The results are expected to be announced on December 18, unless a second round of voting is required.

However, Egypt’s nearly 106 million residents see this as unlikely given Sisi’s record of receiving over 96 percent of the vote in both the 2014 and 2018 elections.

For a brief period, some expected this election to be a tougher race. But the two main opposition figures – who many say had no real hope of winning, but hoped to highlight dissident voices during the campaign – are now in prison or awaiting trial.

After a decade-long crackdown on dissent, Egypt ranks 135th out of 140 countries on the World Justice Project’s rule of law index.

But beyond the political situation, the number-one priority for Egyptians is the faltering economy, which has been in free-fall since early last year.

Egypt’s currency has lost over half of its value since March 2022 in a series of devaluations that have sent consumer prices spiralling in the import-dependent economy. Inflation has hovered near a record high of about 40 percent.

Virtually all goods are imported into Egypt via dollars and the private sector continues to shrink, while public subsidies are disappearing one by one under pressure from the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

The IMF is still waiting to conduct its quarterly reviews after approving a $3 billion loan for Egypt last year conditioned on “a permanent shift to a flexible exchange rate regime”.

It is now the second country, after Ukraine, at the highest risk of a debt crisis, according to an analysis by Bloomberg.

Conscious of voters’ concern for the economy, presidential candidate Hazem Omar of the Republican People’s Party assured them that his first move if elected would be to “control inflation by abolishing VAT on basic foodstuffs”.

He spoke at the only televised debate between candidates, during which Sisi was represented by a member of his campaign.

Another candidate, Farid Zahran, the head of the left-wing Egyptian Social Democratic Party, promised the “release of all prisoners of conscience” – estimated at thousands since Sisi came to power – and the “abolition of repressive laws”.

Germany-based Egyptian journalist and scholar Hossam el-Hamalawy said Sisi’s expected victory “has little to do with popularity or some outstanding economic performance”.

“He will win simply because he controls the executive state institutions and the much-feared security apparatus and has already eliminated any serious contender,” he wrote in a piece for the Arab Reform Initiative.

Ezzat Ibrahim, a member of the government’s human rights council, categorically denies this. “To claim that the elections are a foregone conclusion is to prevent Egyptians from exercising their rights and to promote a bad image of the state,” he told AFP.

In the streets, however, posters and banners proclaiming the support of parties, neighbourhood committees and local figures for the incumbent are ubiquitous.

Conversely, campaign posters for other candidates are few and far between.

In addition to domestic challenges, Hamalawy highlights the impact of the war between the Palestinian militant group Hamas and Israel in the Gaza Strip, neighbouring Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula.

This conflict, he added, “threatens further blows to an already crippled economy, while gradually reviving street dissent”.

On October 20, hundreds of Egyptians diverted a protest in solidarity with Gaza to Cairo’s emblematic Tahrir Square – where in 2011, mass protests led to the overthrow of then-president Hosni Mubarak – before being quickly dispersed.

Ever since, there have been no pro-Palestinian marches authorised in the country, where demonstrations are effectively banned.

As a major interlocutor in the conflict, “Sisi probably hopes that the war in Gaza would provide him with leverage with Western and Gulf governments as well as international donors and that he would be able to use this leverage to ease the country’s economic and financial crisis”, Hamalawy wrote. – Reuters and AFP