Donor funds for South Africa’s Prosecuting Authority: Considerations and implications

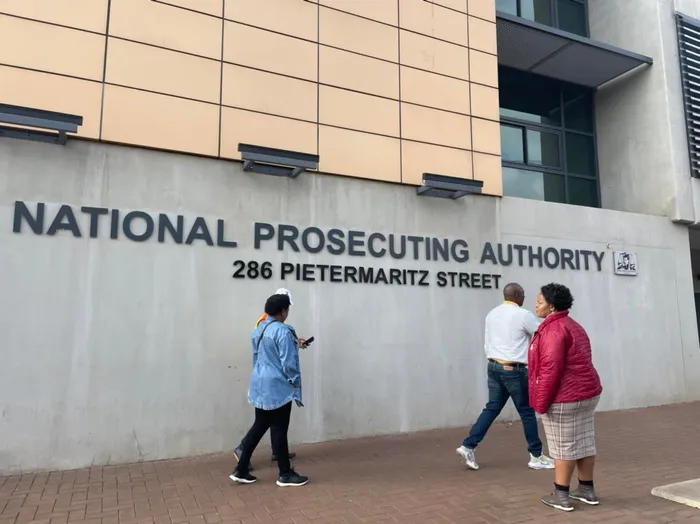

Picture: Supplied – Msunduzi Municipality disconnected services to the National Prosecuting Authority (NPA) building in Pitermaritzburg for an amount of R1 million. The intention of prosecution is to ensure that the rights entrenched in our laws and our contractually bound treaty obligations are meaningfully met.

By Nazreen Shaik-Peremanov

Notwithstanding the political prowess to address the present backlog to undertake prosecutions in South Africa, various other impacting resources and factors play an integral role when embarking on prosecution.

Not only does prosecution give full effect to rights that accrue to individuals within South Africa; but it is also an indicator of effective governance and government. Human rights contained with various rights instruments that arise from South Africa’s legislation, or from treaties to which South Africa is party/Member State, are sources of prosecutorial action.

In an attempt to fulfil these rights and obligations, the Honourable Minister Ronald Lamula announced in early 2023, South Africa’s intention to procure donor funding in order to make good on justice delivered. Mindful of the four pronged duties and obligations that are attendant from rights based instruments, namely fulfil, protect, promote and respect, the South African government and private institutions are legally bound to give effect to the right to justice.

Donor funding emanates from local, regional and international partners. To make use of a trite example, we may perhaps appreciate the functioning of donor funding. When a little girl walks into the local Spar supermarket intending to buy a chocolate bar, for example, she must take into account some critical factors such as the consideration of the brand of chocolate, the size, the taste, the price, inter alia.

In so doing, the little girl creates a rubric of critical factors that inform her decision as to whether she may or not purchase a bar of chocolate. Notably, a simple decision to purchase a chocolate bar has impacting critical factors and the consequent decisions. The little girl may decide to walk into another branded supermarket, a store or a side walk vendor, dependant on her balancing of factors primarily instigated by her buying power.

When donor funding becomes an offer, there are inevitably particular critical presupposed factors that accompanies the offer. The recipient of donor funding has little discretion to vary the terms and conditions of the so-called critical presupposed factors. Recipients must conform to the critical presupposed factors or the donor may very well withdraw donor funding. These critical presupposed factors are minimum requirements are non-negotiable presented to the recipient.

Such minimum requirements are not always congruent with the recipient State’s needs or contexts. For reasons only known to the State recipient, compromises on the acceptance of the donor’s minimum requirements often ensue, which may not always be consonant with the recipient’s initial objective.

Additionally, the values-based priorities typically political, cultural and the like may be significantly diluted losing sight of the other contingent factors within the recipient State’s trite cohort. By this, I mean that the recipient may accede to donor requirements that clash with the recipient’s goals and ideals that inform the spirit, object and purpose of the objective. Consequently, inasmuch as prosecutions may be enabled though donor funding; other aspects such as cultural values may be diluted or eroded.

Take for example, crimes that ensue within the villages of South Africa presided over by traditional systems and values. Western European and Scandinavian nations’ values do not recognise values outside of the traditional western influenced rights, laws and values.

Donor funding may also impose the prosecution of particular crimes such as gender-based violence. By way of example, circumcision is viewed as diametrically opposed to western rights based thinking, initiatives which translate into donor minimum requirements. Whereas circumcision, for example in South Africa, is recognised in as an integral part of initiation, particular rules are imposed by traditional values and systems. As this is encompassed within the South African Constitution, these values propositions that have been in existence time immemorial and vetted by the impacted communities cannot possibly be extinguished by the giving of money for prosecutions pre-determined by another sovereign State, a regional or private entity.

Another aspect that must be considered is that of private donor funding. Simply put, it has often been the case that countries on the African continent have dangerously usurped the rights of beneficiaries in order to undertake part of the work as promised by the African country only to find that much of donor funds have been otherwise abused. Part of the recipient objective, although achieved, came with a well-known high price.

Thus, any State recipient must be extremely careful when assessing the donor’s minimum requirements as against the funding offered. Indeed, it is a most delicate balancing exercise. This delicate balancing exercise cannot have through the use of donor funding, the serious denting or total erosion of prevailing contextual contending ideals.

The Rome Statute which created the International Criminal Court has a general jurisdiction over international crimes committed within the territory of its Member States nations. The International Criminal Court specifically makes use of the words “unwilling” and “unable” in relation to a State’s prosecution. In essence, these two terms inform the State Party’s intention to embark on prosecution. “Unable,” as envisaged by the Rome Statute means, inter alia, the financial ability to undertake prosecutions. Now, most assuredly the International Criminal Court is one avenue of South Africa approaching them to undertake international crimes that the State is unable to prosecute due to financial constraints.

Domestic prosecutions must also be addressed. Fundamentally, a distinction may be drawn between categories of crimes ranking from light to heavy and, finally, egregious crimes. Those crimes that are unconscionable to the human mind, and egregious may easily be transferred to the International Criminal Court.

Thus, we see that plausible and workable alternatives are in place in the international sphere such that South Africa is not necessarily bound by external donor funding.

When South Africa decided on procuring donor funding, much serious thinking must be had in order to ensure that the primary goal of procuring donor funding is in keeping with the ethos, spirit and word of our laws and prevalent values. To do otherwise, would run the risk of attaining the intended goal at a significant loss that results in even greater confounding issues for the nation. As previously stated, the intention of prosecution is to ensure that the rights entrenched in our laws and our contractually bound treaty obligations are meaningfully met. Prosecution is also discretion based in that prosecutorial discretion is applied by the Prosecuting Authority, which may arise from a need to catch the big proverbial fish. South Africa should also take serious cognisance of alternatives such as the International Criminal Court options.

South Africa, must thus ensure that donor funding does not inherently conflict with her intention, which will dilute trite values intimate to her society.

Nazreen Shaik-Peremanov is a lecturer and a supervisor of UNISA’s Doctoral Programme at the University of South Africa.

Related Topics: