Civil society must reclaim leadership role

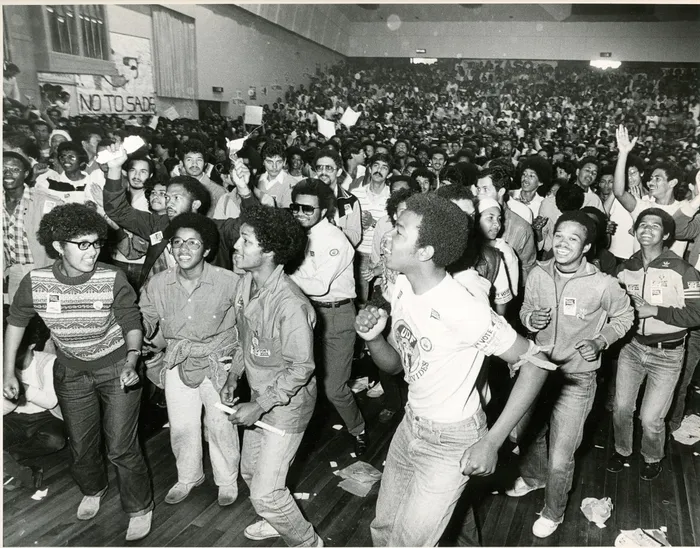

Picture: Willie de Klerk/African News Agency (ANA) Archives – Activists from a range of community organisations at a protest meeting held under the banner of the United Democratic Front (UDF) in Cape Town on August 21, 1984. Instead of war talk or empty slogans, focusing on building our communities through development will ensure an empowered civil society and state, say the writers.

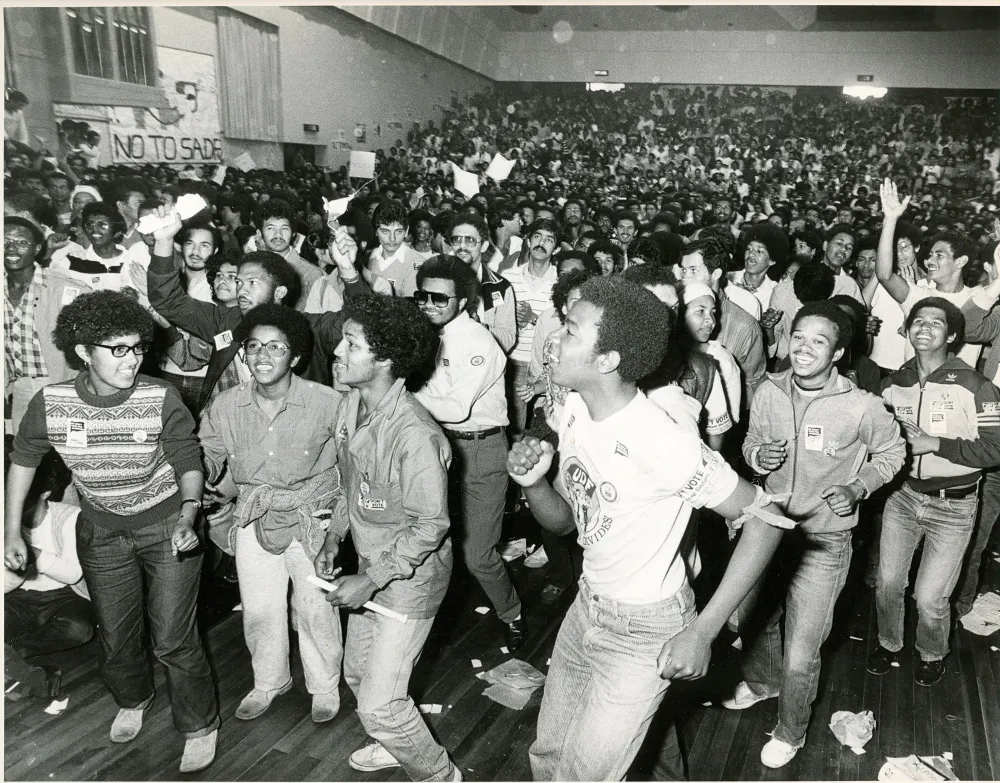

Picture: African News Agency (ANA) Archives – United Democratic Front supporters protest against the apartheid state’s heightened repression in Cape Town, August 1989. Unions, citizens and, after their unbanning, the major liberation forces, held largely peaceful – and massive – protests against the apartheid regime and its criminal and repressive laws. Civil society then was about building towards our democratic and developmental future, say the writers.

By Michael Sutcliffe and Sue Bannister

The past 20 years have witnessed an increasingly violent nature of protest in our country. Research, such as that by Municipal IQ, shows that more than 70 percent of all protests have been violent.

Hardly a day goes by without a media report on public property being damaged; arson or attempted arson; private property threatened and destroyed; residents and, often, the poor and informal traders significantly affected; shops looted; foreign nationals threatened and attacked; and an unnecessary number of people killed or injured.

The protests are usually accompanied by male leaders mobilising through war talk. In response, we deploy inordinately high numbers of security forces to manage the protests, taking them away from their important work in building safer communities. Our own, less researched than experienced in, protests in the 1980s and 1990s were the opposite.

Unions, civics and, after their unbanning, the major liberation forces, held largely peaceful and massive protests against the apartheid regime and its criminal and repressive laws. The protests were organised with a significant number of marshals keeping order and often had our great female (and male) leaders leading us. The State’s response was usually brutal – attacking, inciting, arresting and detaining many in the marches.

Civil society was about building our democratic and developmental future. We took the experience into the negotiations process, and the result was that it provided for the right to protest but, more importantly, it institutionalised community engagement and participation as extremely important means of building our democratic state.

Under the Constitution, municipal legislation in particular is specific about community consultation being required in almost every stage of defining policy, legislation, planning, budgeting and delivery.

We have institutionalised this through mechanisms developed to promote participation and engagement, such as ward committees and community development workers, legislated communication through print and electronic media, Thusong service centres, public hearings, satisfaction surveys, imbizos and community outreach programmes, transformed traditional councils, and other sector-specific forums (Community Police Forums, school governing bodies, street and village committees, NGOs, community-based organisations).

Ward committees have been established to provide a vital link between ward councillors, the community and the municipality and other spheres of the government. However, the 4468 ward committees hardly play any of the roles of enhancing community participation, as defined in law.

Ward committees should have powers and functions being decentralised from the councils as they could take responsibility for working with the municipal administrations in prioritising the fixing of potholes, pavements, streetlights and similar issues. Unfortunately, in spite of institutionalising community participation, there can be little doubt that community-state relationships have weakened over the past 21 years.

In large part, this is because community engagement has generally been reduced to communication by the state to its communities rather than an empowering form of engagement. Community participation has been largely conflated with a more alienating “public participation”, which, while necessary for conveying information, is not sufficient for community engagement that requires communities to be empowered and the State to be willing to engage in ways that build strong partnerships and trust.

What, then, is going wrong? Most importantly, we have become too focused on building a compliant state and not a developmental state. A developmental state, at the least, would begin by telling its people what it is doing. A cursory look at a few websites of national departments gives us some insight. You cannot find in one place on the websites specific details on what is being done developmentally, in which specific communities it is being done, what the budget is and who is appointed to do it.

The information could include:

- Upgrading initiatives in each public school to ensure schools have proper toilets, libraries (Basic Education).

- Which communities are receiving new electricity connections (Eskom and municipalities) or provided with solar panels.

- Where bulk and reticulated water provisions and connections are being undertaken (Water and Sanitation).

- Houses being planned and built, including where and how many (Human Settlements).

- What each of the more than 2 000 mines have promised in their Social Labour Plans that they will do for specific communities (Minerals and Energy).

- What roads are being upgraded, maintained or built (Transport and municipalities).

Imagine how empowering such information would be if it were available. It would allow all our communities to assist the state in ensuring such work does get done, on time and on budget. And this would lead to communities protesting more about how to do things better and faster and would allow them to monitor that we are getting value for money.

By doing this, we would, hopefully, then get a State that stops measuring housing development in terms of how many summits, reports or mass meetings have been delivered, but in terms of how many housing units have been built or homeless people who have been housed, including where they are, who built them and at what cost.

We would soon realise that financial auditors don’t really have the means to measure anything other than financial management, and we would get communities and development specialists to measure progress being made in building a developmental state.

And this would get us talking much more about what we have done in terms of development. We have great accomplishments in that regard, such as, halving the proportion of the population without sustainable access to basic services by 2011, four years before the global target.

Since then, much more has been achieved in this regard as statistics show that 90 percent of households had access to electricity in 2020 compared with 70 percent in 2001; 89.1 percent of households had adequate access to water in 2020 compared with 72 percent in 2001; 83.2 percent of households had access to flush, chemical or ventilated pit toilet compared with 64 percent in 2001; 60.5 percent of households had access to refuse removal in 2020 compared with 55 percent in 2001.

Significantly, too, we created a Constitution and a court that have possibly delivered more judgments about our human rights than any other apex courts in the world. But the judiciary and media themselves lag behind in transformation, and often focus too much on reacting to issues rather than contributing positively to our transformation project.

Completing our need to give access to the basic services, including ICT, and ensuring we repair, rehabilitate and maintain them properly remain greater challenges. Focusing on building our communities through development means, instead of war talk or slogans such as defending our democracy or going to court at every opportunity, is an empowered civil society and state who are focused on building our communities together.

In the process, planning, monitoring and evaluation would also need to radically rethink what they need to do to focus attention on development and, through that, ensure that we build our communities together, listening more than telling, involving more than ignoring and working together rather than apart.

Michael Sutcliffe and Sue Bannister are Directors at City Insight (Pty) Ltd