Citizens’ boycott threats poses a serious threat to democracy

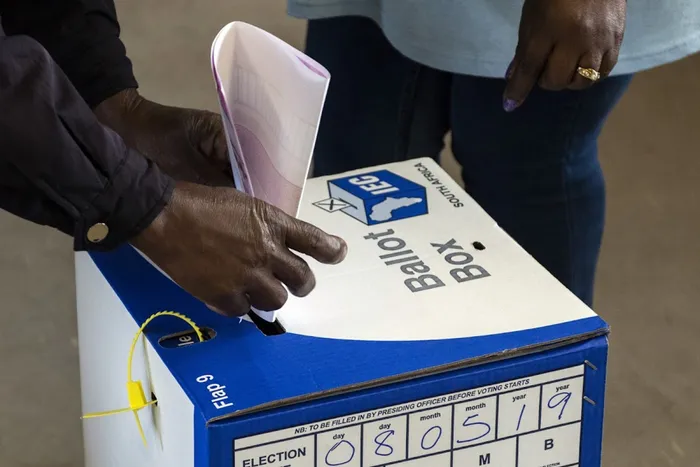

A voter casts his ballot at a polling station during the general election in Soweto, in May 8, 2019. As the 2024 general elections on May 29 nears, and threats of boycotting the polls grow, let us not forget that such boycotts have far-reaching implications for the country’s democratic processes and political landscape, says the writer. – Picture: Bloomberg

By Sethulego Matebesi

On the eve of elections in South Africa, there is a general trend for citizens to threaten not to vote. Staying away from voting is viewed by such activists as a form of protest against the perceived poor performance of the ANC.

Recognising the vulnerability of political parties and leaders during this period, the activists advance that it has become temptingly easy to give in uncritically to the ever-expanding list of existential crises South Africans endure.

But it is also rather too easy to forget that election boycotts can have far-reaching implications for the country’s democratic processes and political landscape.

Some of the deepest and most fundamental challenges of democracy are unemployment and poverty. While informal settlements have been with us for some time, it is astonishing how they sprung up during an election year. There seems to be little reason not to assume this is how community activists demonstrate their power and relevance. Vulnerable citizens in a political culture favouring power and wealth embrace such action.

While boycotting elections is a form of political protest and a legitimate way for citizens to express dissatisfaction with the government or the electoral systems, it can weaken the legitimacy of the electoral process and undermine the representation of diverse voices in government. And in democratic countries like South Africa, the state cannot, in general, constitutionally ban the expression of particular views. On the other hand, boycotting elections can also draw attention to important issues, spark public debate and pressure political leaders to address concerns raised by the boycotters.

Whether boycotts have the desired outcome or not, we should avoid simplistic assumptions about activists. For one thing, calls for boycotting the May 29 elections are consonant with the government’s performance over the past three decades and are not merely a frivolous pastime.

However, whether we sympathise with boycotters or condemn them, we should not ignore that calls for boycotts raise questions about the activists’ tone of entitlement and righteousness.

In this vein, it is prudent to understand that the grave implications of the threats to boycott the forthcoming elections will hurt the ANC and the country’s social, economic and political edifice. While rhetoric for or against boycotts is the run of the mill, when such claims spill out of the court of public opinion and reality sets in, it is often individual boycotters who face the music.

But why do disgruntled citizens wait for an election year to show their frustration?

As we enter the last lap of political campaigning before the elections, threats of boycotts will probably heighten, but no widespread instability is expected.

Academic studies have shown that the effects of boycotts are not significantly different from those of threats of boycotts. Boycott threats demonstrate certain tension and challenges regarding citizens’ responsibility to be actively involved in politics and hold politicians accountable. Activists and boycotters seem to abdicate their responsibility to actively deal with governance and societal challenges beyond elections.

I cannot agree more with my colleague, Dr Harlan Cloete, who argues in his opinion piece, #Elections Countdown: Active citizenship needed to unlock South Africa’s potential, that we tend to focus too (much) on elections per se and “forget that what counts is what takes place between elections”.

Even though there is almost popular acceptance that boycotts are part of the South African political and social landscape, have “all protocols been observed?”

Using the analogy of the customary South African acknowledgement of all the dignitaries present at the beginning of a speech, can we understand the omission to acknowledge those who sacrificed their lives for the democracy we enjoy today? The fact that democratic reform has been blunted or reversed in recent years will always be distorted within courts of public opinion, does not change the fact that threats of boycotts remain central to electoral debates.

At the heart of this discussion is that, despite the grave implications of threats to boycott elections, the country should not follow a hard-line approach as justification for political crackdowns on activists. The threats provide us with a glimpse through the minds of many South Africans who have yet to realise that the political power resides with them and not political office bearers. This and other questions notwithstanding, discouraging citizens from voting enables us to think more deeply about forms of political activism that reject or complicate democratic processes that shape progressive political agendas.

It also offers an important and challenging perspective on the role of strong institutions, respect for the rule of law, civic education and dialogue among all stakeholders in promoting a culture of peaceful, inclusive and transparent elections.

Prof Sethulego Matebesi is Associate Professor and head of the Department of Sociology at the University of Free State

Related Topics: